Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 25 JUN 2025

On 13 June 2025, Israel launched an unexpected series of attacks against military and nuclear facilities in Iran.

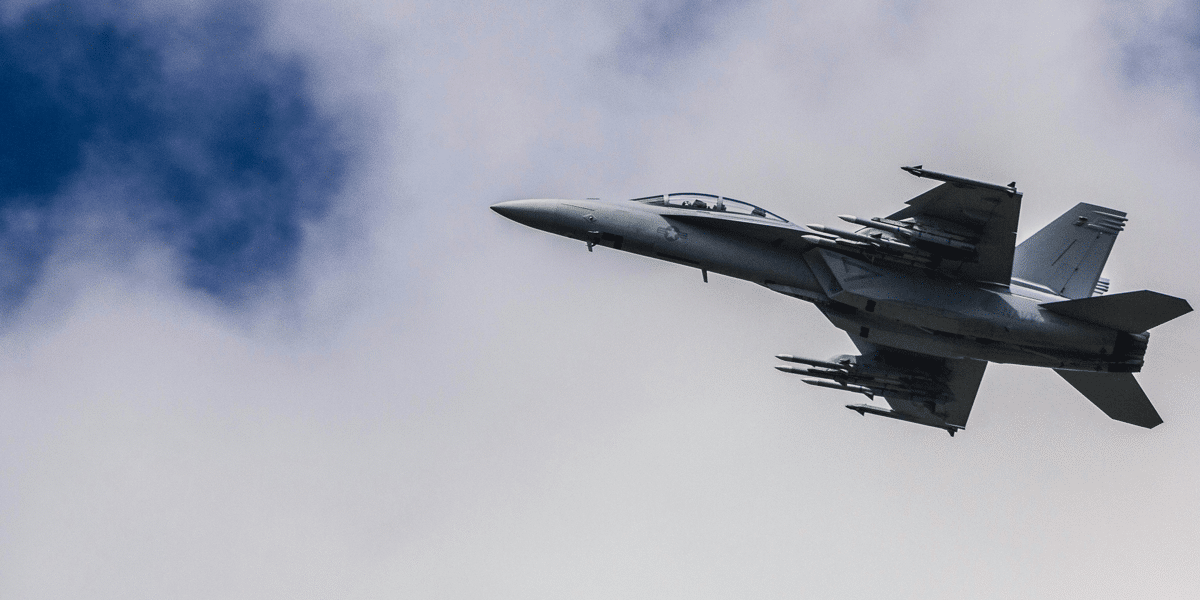

These attacks killed prominent politicians, military personal, and nuclear scientists, seriously damaging Iran’s air defences and its capacity to develop nuclear technology. A week later, the conflict escalated when the United States attacked heavily fortified nuclear facilities with some of its most powerful conventional weapons. President Trump claimed these strikes ‘obliterated’ Iran’s ability to develop nuclear technology.

The actions of Israel and the US have prompted widespread controversy, including questions about their legality, but I’m not interested in whether they had a legal right to strike Iran, but rather in whether these strikes were ethically justified.

Both Israel and the US have justified their attacks as self-defence. So let’s start with the claim that states have a moral right to self-defence. The realist tradition in international relations and international law often takes this right as read; a state has the right to self-defence qua being a state.

But this doesn’t really satisfy the question for someone interested in global ethics.

I, amongst others, ground the state’s right to self-defence in its status as the primary agent of justice with a responsibility to protect the individual human rights of its citizens against aggression. ‘Aggression’ here is limited to the application of direct military force. But what about circumstances where one hasn’t been attacked yet, but there is strong reason to believe that you will be?

This is where people who work in the ethics of war often employ the ‘domestic analogy’ and try to equate the state’s right of self-defence with an individual’s.

Let’s consider two test cases:

You get into an argument with your neighbour, they lose their temper and cock their fist to punch you. Would you be justified in throwing a punch first?

Second, you and your neighbour have been quarrelling. You hear rumours that they’ve been ‘talking trash’ about you and intimating that they are going to punch you when you least expect it. Would you be justified knocking on their door and punching them in the face?

In the case of the former, it seems ridiculous to say that you need to take the punch if you can stop it from coming, while the latter case seems unjustifiably aggressive. In one case the threat to you is imminent and unavoidable; the blow is coming unless you hit first. In the other case there is no imminent threat; it is in the future and there may be ways of de-escalating the conflict, such as a conciliatory fruit basket, or by calling the police.

If this analysis is correct, then a state may pre-empt an incoming attack when it has reliable intelligence that a hostile neighbour is mobilising for war, but it cannot do so based on the fear of a future attack that may be an unknown time away. In the case of Israel and Iran, it does not seem that Iran was on the cusp of attacking Israel, let alone attacking the United States. It’s analogous to the second test case, not the first.

However, the ‘domestic analogy’ does not seem to accurately encapsulate the ethical dilemmas that states face when considering the use of violence in self-defence.

The international system involves risks far beyond the type posed by personal self-defence, and the state has a responsibility to meet them as part of its duty to protect the rights of those within its borders

The question is whether in June 2025 Iran was able to put the basic rights of Israelis under sufficient threat to justify starting a war? The answer hinges on the prospect of Iran possessing – in the future – a relatively small arsenal of nuclear weapons. This would pose an existential threat to Israel in two ways. The first is their simple but immense destructive power; Israel is not a large country, so a few medium yield nuclear weapons would be enough to destroy its ability to defend itself and would kill potentially millions of non-combatants. Iran, however, does not need to use these weapons for them to be a threat. The second is that their existence would check Israel’s own (unacknowledged) nuclear arsenal and leave it vulnerable to a conventional war from its neighbours in which it would be at a possibly fatal disadvantage. It seems reasonable to say that a nuclear armed Iran would pose an existential threat to Israel’s ability to preserve the rights of those within its borders. However, it must be noted Iran certainly does not pose the same kind of existential threat to those within the USA.

This, however, does not settle the matter, because a key element of self-defence is that it can only occur when all other reasonable alternatives have been exhausted. It seems hard to imagine that this was the case. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreed in 2015 between Iran, the UN P5+1 and the European Union showed that there was at least a chance for a diplomatic solution to the Iran nuclear issue. This may be viewed as naïve by those who support Israel’s action, that it is the equivalent of hoping a fruit basket would appease the Mullahs, but it is not a wild utopian flight of fancy and these attacks are not without cost.

We must weigh the consequences of stretching the right of self-defence, because it is increasingly coming to look like a fig-leaf for a world where might makes right.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture