Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 12 JAN 2026

‘We live in a world, in the real world… that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world that have existed since the beginning of time.’ These are the words of Stephen Miller, Deputy Chief of Staff in the Trump White House, while refusing to rule out the possibility of the United States annexing Greenland.

Miller is not an isolated voice. President Trump has escalated his annexationist rhetoric about Greenland as essential to American security and has said that they will ‘take’ the Danish territory whether they ‘like it or not.’

These sentiments have a striking similarity to what the historian and general Thucydides wrote during the Peloponnesian War over two thousand years ago:

‘You know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in powers, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.’

This is the foundation of realism, a philosophy of foreign affairs. It claims that in an anarchic international system, the only rational policy for a state is to pursue its own security by having more power than its neighbours. This is because, in the absence of a world state, power is the final arbiter of disagreements between states.

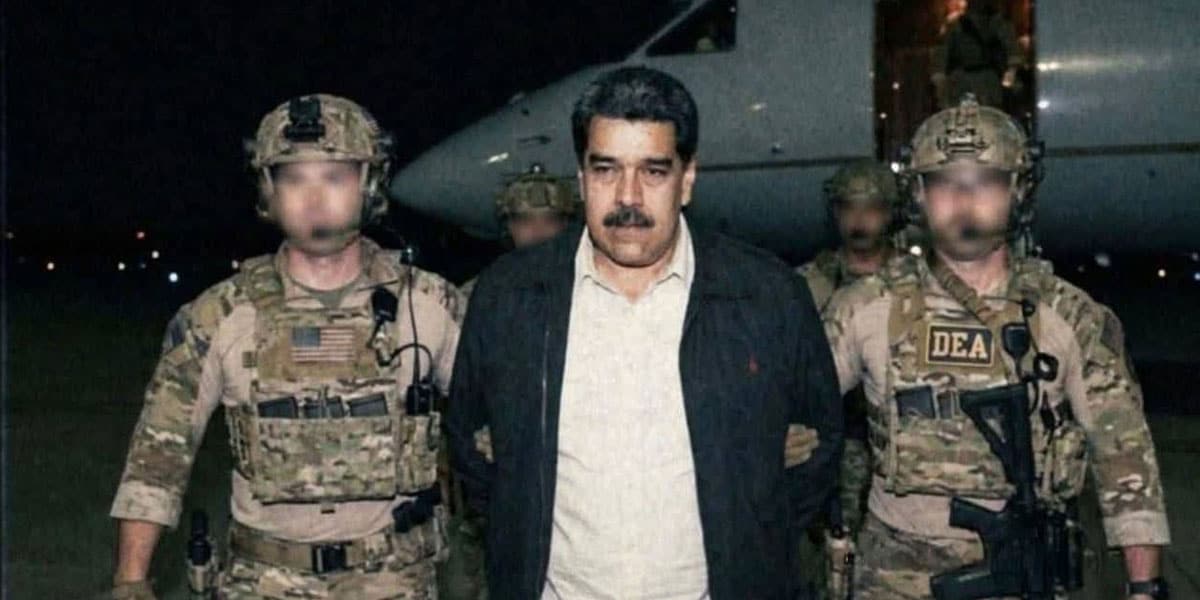

On the back of the abduction of then-Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and the Trump administration’s apparent willingness to allow Ukraine to be subsumed into a Russian sphere of influence, it seems a new realism has taken root in American foreign policy. It is one that has pushed away ethical concerns about human rights and international law and embraced pure power politics. Might makes right, and weaker countries like Venezuela, Denmark, and perhaps Canada must accept their place as mere vassals of Washington.

The problem is that Miller and Trump are not good realists.

Realism is not amoral or unethical. It has an ethical core that is practical, modest, and conservative. Realist ethics do not license something as reckless as kidnapping foreign heads of state, fracturing NATO to seize Greenland, or letting an aggressive rival menace allies. These are acts of bravado, performative and imprudent. Such actions invite unintended and unpleasant consequences.

The vulgar realism of the Trump administration would have appalled Hans Morgenthau, one of the founders of modern realism and advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Although he was attentive to power, Morgenthau never said that there was no such thing as ethics in international politics, but rather that it has a distinct set of ethics that requires a balance of power and principle. He wrote in Politics Among Nations:

‘A man who was nothing but ‘political man’ would be a beast, for he would be completely lacking in moral restraints. A man who was nothing but ‘moral man’ would be a fool, for he would be completely lacking in prudence’

Realist ethics are about survival and security in a complex, dangerous, and unpredictable world. It is wary of transcendent ideas about universal morality because of the crusader spirit they engender. Morgenthau was deeply worried that zealots on both sides of the Cold War might start a nuclear war in the name of democracy or Marxism-Leninism to the detriment of all humanity.

Likewise, the unethical bestial pursuit of power also invites disaster because it can result in a loss of the very thing it seeks to gain. Miller clearly never finished Thucydides’ The History of the Peloponnesian War (and Trump probably has no idea what it is). Athens lost the war and Sparta imposed a harsh peace. The words of the ‘Melian Dialogue’ quoted above serve to highlight the hubris of Athens. They frightened neutral states with their brutality, alienated allies with their high-handedness, and convinced of their own superiority made disastrous military adventures, such as the Sicilian Expedition, which ultimately diminished their power and prestige. In acting like Morgenthau’s beast they authored their own downfall. Hubris and tragedy are themes in the realist tradition.

The actions of the Trump administration threaten to undo the undeniable triumph of American foreign policy which was to turn the wealthy democracies of Europe into dependent but dependable allies. It invites a future where NATO has dissolved, but a rearmed, independent, and unified Europe has taken its place and that views the United States as an unreliable or even hostile power. The consequences of this shift cannot be overstated. A united Europe would have an economy five times the size of India, ten times the size of Russia, and comparable to China in nominal GDP. It would be able to check American influence, especially if it acted in concert with China. America would no longer be a hegemonic power, but simply a great power in an unstable multipolar order.

Hubris, tragedy and an object lesson on how not to be a realist.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What it means to love your country

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights