Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Jack Hume The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2016

For the most part, we respect our colleagues and probably wouldn’t ever label them ‘sexist’ and certainly not ‘racist’. But gender and ethnic diversity in workplaces shows something is amiss.

Women fare worse than men across most measures of workforce equity. The Australian Government’s Gender Equality Agency report notes women who work full-time earn 16 percent less per week than men, constitute 14 percent of chair positions, 24 percent of directorships and 15 percent of CEO positions.

Women lose at both ends of the career lifecycle. Their average graduate salaries are 9 percent less than their male equivalents’ and their average superannuation balances 53 percent less.

Sociology, psychology and gender and cultural studies have all weighed in on the multiple causes of these inequalities, with much of the conversation converging around the role of ‘unconscious bias’ in decision-making.

Applicants with Indigenous, Chinese, Italian and Middle Eastern sounding names were seen to be systematically less likely to get callbacks than those with Anglo-Saxon names.

Studies in which people are asked to evaluate the capabilities and aptitudes of a job candidate show effects of implicit biases on job assessment. In a study mimicking hiring procedures for math related jobs, male candidates fared so much better than women that lower-performing males were chosen over better female candidates.

Similar effects have been seen with regard to race. In Australia, applicants with Indigenous, Chinese, Italian and Middle Eastern sounding names were less likely to get callbacks than those with Anglo-Saxon sounding names.

When biases become socially reinforced, individuals can come to see them as ‘reality’. Studies have shown women tend to believe they are worse at math than men and this belief has a negative impact on their performance.

In one study, a group of women were asked their gender prior to math tests and performed worse than the group who weren’t asked to disclose it. This phenomenon is called the ‘stereotype threat’ and it extends to racial beliefs. Two decades ago, a landmark study found that asking students of colour to identify their ethnicity prior to a test resulted in a substantially poorer grade.

This evidence suggests human resource departments might consider adopting hiring procedures that don’t require race, gender or even an applicant’s name be stated. Of course, at some point, the candidate will need a face-to-face interview, so this isn’t a perfect solution to bias- but it does reduce its influence.

Volunteering to learn more about diversity signifies a more general willingness to open organisational culture to people from different backgrounds.

Alongside systematic and procedural changes, we can help cultivate organisational willingness to combat inequality through diversity training. These training programs rose to prominence around a decade ago as a result of a wave of lawsuits against major US companies. However, as Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev explained in an article for the Harvard Business Review, they were dazzlingly unsuccessful — resulting in negative outcomes for Asians and Black women, whose representation dropped an average of five and nine percent, respectively.

Dobbin and Kalev suggest the major reason these programs failed is probably because they were usually mandatory. This suggests they were motivated more by risk aversion — ‘discriminate and you’ll be fired’ — than a genuinely held belief diversity is valuable. It’s not surprising systematic change didn’t occur under such conditions.

At the same time, companies who used voluntary diversity programs saw increases in black, Asian and Hispanic representation – even as the average was decreasing nationwide. Volunteering is most likely motivated by a belief that diversity is genuinely valuable — factors that seem far more effective in influencing workplace diversity, perhaps because they are genuine.

Science is yet to tell us whether we can actually reduce biases let alone erase them altogether. All the same, we can begin to mend workplace inequalities by actively engaging peoples’ will to change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

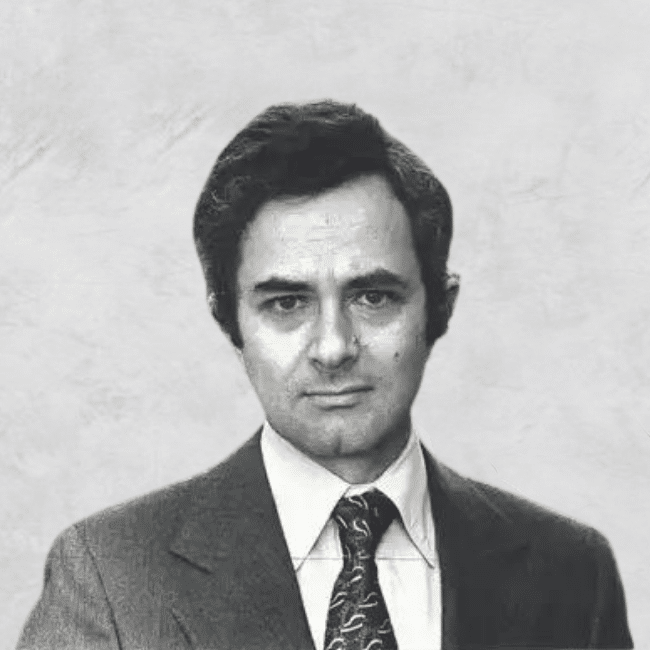

BY Jack Hume

Jack studied Philosophy and Psychology at the University of Sydney, completing his Bachelor of Arts in 2017 with First Class Honours. He has supported The Ethics Centre's Advice & Education team in research capacities over the last two years, contributing to their work on cognitive bias in decision making, and ethics education in financial services. In 2018, he joined the Centre full-time as a Graduate Consultant. He brings insights from contemporary political philosophy, moral psychology and skills in qualitative research to consulting projects across a variety of sectors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Want men to stop hitting women? Stop talking about “real men”

Want men to stop hitting women? Stop talking about “real men”

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2016

“Real men don’t hit women,” declared Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in 2015, before announcing a significant domestic violence funding package.

This slogan was also routinely utilised by former Prime Minister Tony Abbott and is a long-standing feature of prevention and education campaigns around the world.

The message is one many people support. On the face of it, it serves the dual purpose of shaming domestic violence perpetrators and reinforcing the masculinity of non-violent men.

It’s interesting this message is most often delivered by stereotypically successful men such as politicians, sports stars and celebrities. In this way, men and boys are encouraged to see refraining from bashing women as another masculine accomplishment that deserves recognition and acclaim.

We are assured we can be “real men” and enjoy all the perks of masculinity without needing to resort to violence against women. Apparently, not hitting women makes our masculinity even more ‘real’.

On closer inspection, it seems peculiar to celebrate men and boys for not engaging in obviously illegal and harmful behaviour. What is it about violence against women that prompts us to proclaim the masculinity of men who eschew it?

Sexism is so pervasive in our society it becomes invisible, like the air we breathe. It produces the conditions in which domestic violence takes place and then seeps into the solutions we propose for domestic violence. It would be inappropriate to tell white supremacists they can still be ‘racially pure’ without racial violence. “Real whites don’t hit blacks” might ostensibly be an anti-violence message but it hinges on the very notion of racial purity causing the violence.

In the same way, “real men don’t hit women” only makes sense within the culture of sexism that drives violence against women. Male anxiety about being a “real man” is at the very core of physical and sexual violence.

Men who identify strongly with traditional, stereotypical notions of masculinity are most at risk of perpetrating domestic violence. Boys raised in a culture of masculine entitlement can grow into men who feel disrespected and turn to violence when they don’t receive the status and deference they expect from their partner.

Messages about “real men” are not part of the solution to domestic violence. They are part of the problem. Every Australian man grows up being told “real men don’t hit women”. We are taught “real men” are naturally strong and aggressive, but women are too weak and defenceless to make legitimate targets.

Instead, we are encouraged to direct our violence against each other, usually through sport (or physical combat after a few beers). Manfully protecting women is another way of proving our masculinity to others.

“Real men don’t hit women” suggests violence against women is wrong because it is cowardly. It supports the stereotypical view of women as too weak to defend themselves. In fact, women regularly strike back against domestic violence. As a domestic violence worker said during a research interview recently, “Not all of our DV victims are the meek, quiet woman who doesn’t speak up for herself, you know”.

Women who exercise their right to defend themselves against male violence are often stigmatised. They defy sexist expectations that “real women” are too weak to protect themselves and need a “real man” to rescue them.

We won’t stop violence against women by promoting gender stereotypes. The man least likely to hit or abuse a woman is someone who doesn’t care if he’s a “real man” or not. He’s found fulfilling relationships that don’t depend on other people’s assessments of his masculinity.

The good news is these are exactly the relationships men are looking for. No boy grows up hoping to turn into a violent partner or abusive father. Boys and men want to be part of strong relationships, healthy families and happy communities.

Violence corrodes relationships and leaves men alienated, confused and dependent on empty macho displays for a momentary sense of self-esteem. That’s the cost of worrying constantly about being a “real man”. Leaving that anxiety behind opens up a raft of opportunities for boys and men to engage with the people we care about on the basis of mutual respect.

Male violence is an obstacle to the kinds of lives men want to lead. This is the message we should be taking to men and boys.

If you or someone you know is affected by sexual assault or domestic violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732. In an emergency, call 000.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships