Ethics Explainer: Perfection

We take perfection to mean flawlessness. But it seems we can’t agree on what the fundamental human flaw is. Is it our attachment to things like happiness, status, or security – things that are about as solid as a tissue? Our propensity for evil? Or is it our body and its insatiable appetite for satisfaction?

Four different philosophical traditions have answered this in their own ways and tell us how we can achieve perfection.

Platonism

Plato’s idea of perfection is articulated in his Theory of Forms. The Forms represent the abstract, ideal moulds of all things and concepts in existence, rather than actual things themselves. In short, the idea of something is more perfect than the tangible thing itself.

Take ‘red’ for example. Each of us will have a different understanding of what this means – red lipstick, a red brick house, a red cricket ball… But these are all different manifestations of red so which is the perfect one? For Platonists, the perfect, ideal, universal ‘red’ exists outside of space and time and is only discoverable through lots and lots of philosophical reflection.

Plato wrote:

He will do this [perceive the Forms] most perfectly who approaches the object with thought alone, without associating any sight with his thoughts, or dragging in any sense perception with his reasoning, but who, using pure thought alone, tries to track down each reality pure and by itself, freeing himself as far as possible from eyes, ears, and in a word, from the whole body, because the body confuses the soul and does not allow it to acquire truth and wisdom whenever it is associated with it.

In Platonist thought, the body is a distraction from the abstract thought necessary for philosophical speculation. Its fundamental flaw? Its carnal desires that shackle the soul.

Perfection for the individual, to sum up, is the arrival back to the soul’s state of pure contemplation of the Forms. This out of body state of contemplation is far from the idea of the perfect face and physique we often think about today. Indeed, a perfect physical form for Palto is impossible. It is all in the imagination.

Hinduism

In Hinduism’s Advaita school of philosophy, perfection means the full comprehension and acceptance of Oneness.

It’s when you realise your soul (or your atman) is the same as everyone else’s and you are all part of the one, unchanging, metaphysical reality (the Brahman). In this state of realisation, the always changing, material world of maya reveals itself to be an illusion and anything attached to this world, including your actions, are illusions as well. (There are parallels with this and the idea of Plato’s Cave, which is narratively conceived of in The Matrix.)

To attain this status of perfection, an individual must surrender to their caste role and perform that duty to excellence. No matter what they did, they would understand their actions had no effect on the Brahman and to believe so, was a trick of the ego. They focused on renouncing all earthly desires and striving to become completely detached from the world through the specific rituals of their caste role.

Krishna said:

A man obtains perfection by being devoted to his own proper action. Hear then how one who is intent on his own action finds perfection. By worshipping him [Brahman], from whom all beings arise and by whom all this is pervaded, through his own proper action, a man attains perfection … He whose intelligence is unattached everywhere, whose self is conquered, who is free from desire, he obtains, through renunciation, the supreme perfection of actionlessness. Learn from me, briefly, O Arjuna, how he who has attained perfection, also attains to Brahman, the highest state of wisdom.

By “actionlessness”, Krishna means the supreme effort of surrendering everything, including your own actions, so they become “non-action”. If everything is an illusion in the face of Brahman, we mean everything.

Christianity

A sainted bishop named Gregory of Nyssa classified perfection as being and acting just like God’s human form, Christ – that is, completely free of evil. Nyssa said:

This, therefore, is perfection in the Christian life in my judgement, namely, the participation of one’s soul and speech and activities in all of the names by which Christ is signified, so that the perfect holiness, according to the eulogy of Paul, is taken upon oneself in “the whole body and soul and spirit”, continuously safeguarded against being mixed with evil. Perfection lies in the total transformation of the individual. He/she must live, act, and essentially, be all that Christ was, meaning that, as Christ was God manifest in human form, completely free from evil, so too the Christian individual must sever all evil from his/her being.

While the Socratic ideal of perfection requires pure “abstract” thought, and the Hindu ideal requires sublimating individualism into Oneness, the Christian ideal requires cultivating the characteristics of Christ and expelling all that is unlike him from yourself.

Sufism

The Sufi scholar Ibn ‘Arabi had a concept of perfection that echoes the three discussed above. For him, perfection is the individual’s complete knowledge of the abstract and the material, leading to a prophetic (or Christ like) character.

Let’s break that down. He says:

The image of perfection is complete only with knowledge of both the ephemeral and the eternal, the rank of knowledge being perfected only by both aspects. Similarly, the various other grades of existence are perfected, since being is divided into eternal and non-eternal or ephemeral. Eternal Being is God’s being for Himself, while non-eternal being is the being of God in the forms of the latent Cosmos.

The beginning of the passage states that perfection requires knowledge of the eternal and the material. The eternal is God in Himself, and the non-eternal is the Cosmos, including humanity, who in striving for the perfection of the eternal, expresses it.

But Ibn ‘Arabi stresses neither of these knowledges negate the other. In fact, by learning only of the eternal, or only of the material, both would be incomplete since they are simply different manifestations of the same Being. Perfection, then, is not about negation – but continual striving to transformation. Onwards and upwards!

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

“The pen would smoothly write the things it knew, but when it came to love it split in two, a donkey stuck in mud is logic’s fate – Love’s nature only love can demonstrate.” – Rumi

Rumi (1207—1273) has long been recognised as one of the most important contributors to Islamic literature and Sufism, the spiritual and mystic element of Islam. His enormous collection of mystical poetry is considered among the best that has ever been produced. His seminal text is the Masnavi, a six book poem written in rhyming couplets. It is so revered as an expression of Godly knowledge that it is referred to as “The Koran in Persian”.

What is Sufism?

To understand Rumi, you need to understand Sufism. It is often misrepresented as a sect, school, or deviant form of Islam but is better described as a distinct stream in Islamic spirituality. Sufism was first embodied by Muhammad and his early followers, then medieval scholars like Abu Hamid Al-Ghazzali, Ibn Arabi, and of course, Rumi.

Sufism is characterised by its focus on moral cultivation and establishing a personal connection to God through reforming, disciplining, and purifying the ego. It seeks to attain this intuition of God through disciplines that practice an austere lifestyle known as ascetism. One example of this is dhikr, a form of worship where you become absorbed in rhythmic repetitions of God’s name.

Sufism seeks a type of knowledge outside worldly intellect – one that is intuitive and is inextricably tied to the Divine.

Life of Rumi

Rumi, known in Iran and Central Asia as Mowlana Jalaloddin Balkhi, was born in 1207 in the province of Balkh, which is now the border region between Afghanistan and Tajikistan. His family left when he was a child shortly before Genghis Khan and his Mongol army arrived. They settled permanently in Konya, central Anatolia, which was formerly part of the Eastern Roman Empire. Rumi was probably introduced to Sufism through his father, Baha Valad, a popular preacher who also taught Sufi piety to a group of disciples.

The turning point in Rumi’s life came in 1244 when he met a wandering Sufi in Konya called Shamsoddin of Tabriz. Shams, as he was most often referred to by Rumi, taught him the most profound levels of Sufism, transforming him from a devout religious scholar to an ecstatic mystic.

Rumi died on 17 December 1273 shortly after completing his work on the Masnavi. His passing was deeply mourned by the citizens of Konya, including the Christian and Jewish communities. His disciples formed the Mevlevi Sufi order and named it after Rumi, whom they referred to as ‘Our Master’ (which translates to Mevlana in Turkish and Mowlana in Persian). They are better known in the West as the Whirling Dervishes, because of the distinctive dance they now perform as one of their central rituals.

Rumi’s death is commemorated annually in Konya, attracting pilgrims from all corners of the globe and every religion. The popularity of his poetry has risen so much in the last couple of decades that the Christian Science Monitor identified him as the most published poet in America in 1997 and UNESCO declared 2007 to be the Year of Rumi.

Overvaluing intellect

Rumi, like most Sufis, praised the intellect and considered its refinement a religious imperative. But he was clear about the types of knowledge he believed it could sufficiently possess. He considered o domain the sentimental and material world, not the theoretical and metaphysical one.

Rumi’s caution was this: when one relies solely on their own intellect to understand Being and Reality, they risk confining their understanding to a mortal and ultimately finite resource – themselves. He regarded it a folly of the ego to believe one’s intellect limitless and warned against reducing God to abstract puzzles in order to maintain that belief. Rumi scorned placing the intellect too high and pursuing knowledge for knowledge’s own sake.

“He knows a hundred thousand superfluous matters connected with the (various) sciences, (but) that unjust man does not know his own soul.

He knows the special properties of every substance, (but) in elucidating his own substance (essence) he is (as ignorant) as an ass.” – Rumi

The transcendence of man

So, if intellect isn’t enough, what is? Rumi would say, ‘Divine love.’

This divine love can also be translated as grace or friendship with God. In the Islamic worldview, humanity is unique in its capacity to autonomously know God, and this gives people an honoured status. Even so, no human can achieve divine love out of their own efforts. They can only be granted it.

Rumi was of the view that seeking essential knowledge – knowledge about the essence of humanity – was a way one might be granted divine love. It was the best type of knowledge, because it was tied to questions of meaning, purpose, and death. In other words, knowing yourself was a means of knowing God.

According to the Sufis, knowledge of God comes in three levels: material, conceptual, and experiential. Think of it as the different between knowing an apple exists, reading a detailed Wikipedia page about it, and eating one in the flesh. All three are different forms of knowing what an apple is – but each deepens in understanding. The last level is transformative in a way the other two are not. Try explaining what an apple tastes like to someone who has never had one. You may come very close, but they will never know what you mean unless they take a bite themselves.

Likewise, the Sufis believed that the highest knowledge of God was something that could only be experienced. To read and contemplate upon God or the universe was one thing. But experiencing God was something totally different, something impossible to intellectualise.

Rumi believed manifesting the four virtues – courage, wisdom, and temperance, which when balanced, lead to perfect justice, the fourth virtue – would lead to some form of transcendence above the hubbub of life’s claims and counterclaims. But when every human being’s views cannot be divorced from their experience, how was this possible?

For Rumi, this highlighted humanity’s dependence on God. Only a friend of God, or Wali, could be objective enough to see truth and loving enough to be just.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

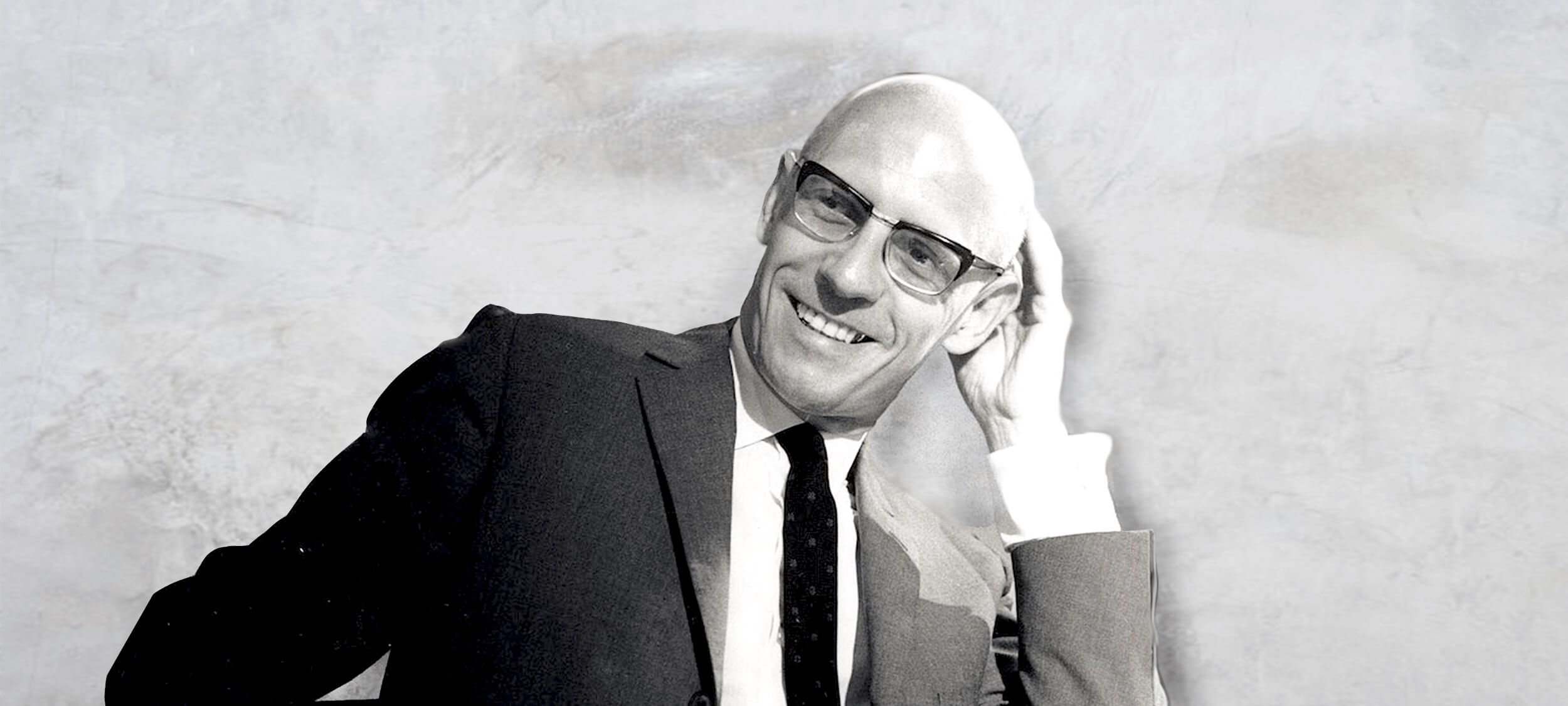

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships