From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2018

We’ve got NEGs, NEMs, and Finkels a-plenty. Here is a cheat sheet for this whole energy debate that’s speeding along like a coal train and undermining Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s authority. Let’s take it from the start…

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – 1992

This Convention marked the first time combating climate change was seen as an international priority. It had near-universal membership, with countries including Australia all committed to curbing greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol was its operative arm (more on this below).

The Kyoto Protocol – December 1997

The Kyoto Protocol is an internationally binding agreement that sets emission reduction targets. It gets its name from the Japanese city it was ratified in and is linked to the aforementioned UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Protocol’s stance is that developed nations should shoulder the burden of reducing emissions because they have been creating the bulk of them for over 150 years of industrial activity. The US refused to sign the Protocol because the two largest CO2 emitters, China and India, were exempt for their “developing” status. When Canada withdrew in 2011, saving the country $14 billion in penalties, it became clear the Kyoto Protocol needed some rethinking.

Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) – 1998

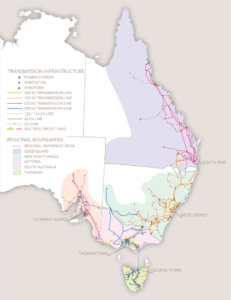

Forget the fancy name. This is the grid. And Australia’s National Electricity Market is one of the world’s longest power grids. It connects suppliers and consumers down the entire east and south east coasts of the continent. It spans across six states and territories and hops over the Bass Strait connecting Tasmania. Western Australia and the Northern Territory aren’t connected to the NEM because of distance.

Source: Australian Energy Market Operator

Source: Australian Energy Market Operator

The NEM is made up of more than 300 organisations, including businesses and state government departments, that work to generate, transport and deliver electricity to Australian users. This is no mean feat. Before reliable batteries hit the market, which are still not widely rolled out, electricity has been difficult to store. We’ve needed to continuously generate it to meet our 24/7 demands. The NEM, formally established under the Keating Labor government, is an always operating complex grid.

The Paris Agreement aka the Paris Accord – November 2016

The Paris Agreement attempted to address the oversight of the Kyoto Protocol (that the largest emitters like China and India were exempt) with two fundamental differences – each country sets its own limits and developing countries be supported. The overarching aim of this agreement is to keep global temperatures “well below” an increase of two degrees and attempt to achieve a limit of one and a half degrees above pre-industrial levels (accounting for global population growth which drives demand for energy). Except Australia isn’t tracking well. We’ve already gone past the halfway mark and there’s more than a decade before the 2030 deadline. When US President Donald Trump denounced the Paris Agreement last year, there was concern this would influence other countries to pull out – including Australia. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott suggested we signed up following the US’s lead. But Foreign Minister Julie Bishop rebutted this when she said: “When we signed up to the Paris Agreement it was in the full knowledge it would be an agreement Australia would be held to account for and it wasn’t an aspiration, it was a commitment … Australia plays by the rules — if we sign an agreement, we stick to the agreement.”

The Finkel Review – June 2017

Following the South Australian blackout of 2017 and rapidly increasing electricity costs, people began asking if our country’s entire energy system needs an overhaul. How do we get reliable, cheap energy to a growing population and reduce emissions? Dr Alan Finkel, Australia’s chief scientist, was commissioned by the federal government to review our energy market’s sustainability, environmental impact, and affordability. Here’s what the Review found:

Sustainability:

- A transition to low emission energy needs to be supported by a system-wide grid across the nation.

- Regular regional assessments will provide bespoke approaches to delivering energy to communities that have different needs to cities.

- Energy companies that want to close their power plants should give three years’ notice so other energy options can be built to service consumers.

Affordability:

- A new Energy Security Board (ESB) would deliver the Review’s recommendations, overseeing the monopolised energy market.

Environmental impact:

- Currently, our electricity is mostly generated by fossil fuels (87 percent), producing 35 percent of our total greenhouse gases.

- We’re can’t transition to renewables without a plan.

- A Clean Energy Target (CET), would force electricity companies to provide a set amount of power from “low emissions” generators, like wind and solar. This set amount would be determined by the government.

-

- The government rejected the CET on the basis that it would not do enough to reduce energy prices. This was one out of 50 recommendations posed in the Finkel Review.

ACCC Report – July 2018

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry Report drove home the prices consumers and businesses were paying for electricity were unreasonably high. The market was too concentrated, its charges too confusing, and bad policy decisions by government have been adding significant costs to our electricity bills. The ACCC has backed the National Energy Guarantee, saying it should drive down prices but needs safeguards to ensure large incumbents do not gain more market control.

National Energy Guarantee (NEG)– present 20 August 2018

The NEG was the Turnbull government’s effort to make a national energy policy to deliver reliable, affordable energy and transition from fossil fuels to renewables. It aimed to ‘guarantee’ two obligations from energy retailers:

- To provide sufficient quantities of reliable energy to the market (so no more black outs).

- To meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement (so less coal powered electricity).

It was meant to lower energy prices and increase investment in clean energy generation, including wind, solar, batteries, and other renewables. The NEG is a big deal, not least because it has been threatening Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership. It is the latest in a long line of energy almost-policies. It attempted to do what the carbon tax, emissions intensity scheme, and clean energy target haven’t – integrate climate change targets, reduce energy prices, and improve energy reliability into a single policy with bipartisan support. Ambitious. And it seems to have been ditched by Turnbull because he has been pressured by his own party. Supporters of the NEG feel it is an overdue radical change to address the pressing issues of rising energy bills, unreliable power, and climate change. But its detractors on the left say the NEG is not ambitious enough, and on the right too cavalier because the complexity of the National Energy Market cannot be swiftly replaced.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 20 AUG 2018

Feminist firebrand or second wave scourge? When The Female Eunuch was published to international success, it was obvious Germaine Greer (1939—present) had hit a nerve – something she continues to do.

This article contains language and content that may be offensive to some readers.

Germaine Greer is an Australian writer and public intellectual who rose to international influence with her book published in 1970, The Female Eunuch. It was a watershed text in second wave feminism, a bestseller around the world, and it made Greer a household name.

Greer’s infamously bold voice and sense of humour permeates throughout the book. Her strong character and take no prisoners approach to public debate saw her regularly contribute to panels and broadcast media. Greer was launched into the public eye as a young, bolshie feminist star.

Since then, Greer has written many books spanning literature, feminism and the environment. She has become one of Australia’s most ‘no-platformed’ thinkers. Almost five decades on, we take a look at her contributions to feminist philosophy.

Human freedom is intrinsically tied to sexual freedom

Greer is a liberation, rather than equality feminist. She believed achieving true freedom for women meant asserting their uniquely female difference and “insisting on it as a condition of self-definition and self-determination”.

Greer wanted to be certain about this female difference, and for her, this certainty started with the body.

You can think of Greer’s claims like this:

- Women are sexually repressed.

- Men are not sexually repressed.

- The difference between men and women is their biological sex.

- Biological sex determines if you’re sexually repressed or not.

The second part of her argument is as follows:

- Women are expected to be ‘feminine’.

- Women are sexually repressed.

- The expectation to be ‘feminine’ is sexually repressive.

Greer is scathing in her portrayal of ‘femininity’. She claimed it kept women docile, repressed, and weak. It stifled women’s sexual agency, hence the ‘eunuch’, which was intrinsically tied to their humanity.

Only by liberating women sexually could they remove this imposed submissiveness and embrace the freedom to live the way they wanted.

“The freedom I pleaded for twenty years ago was freedom to be a person, with dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood. Freedom to run, shout, talk loudly and sit with your knees apart.” – Germaine Greer (1993)

A feminist utopia is an anarchist utopia first

In the London Review of Books 1999, Linda Colley wrote, “Properly and historically understood, Greer is not primarily a feminist. More than anything else, she should be viewed as a utopian.”

For Greer, the greatest danger of the widespread female eunuch is not an unfulfilling sex life. It is in her being so concerned with femininity that she is incapable of political action. Greer believed this social conditioning was dire and its enforcers so embedded that revolution rather than reform was required.

Greer called for this revolution to start in the home. She spoke openly about topics that at the time were taboo: menstruation, hormonal changes, pregnancy, menopause, sexual arousal and orgasm. She decried the agents of femininity that she felt kept women trapped: makeup, constricting clothing, feminine hygiene products, stifling marriages, misogynistic literature and female sexual competitiveness. She reserved her greatest fury for widespread consumerism, which she believed kept women dependent on the systems that forged their own oppression.

Like Mary Wollstonecraft before her, Greer argued neither men nor women benefited from this. She called upon women to rebel again these “dogmatists” and create a world of their own. But the solution she presents is exploratory instead of pragmatic. Perhaps women could live and raise their children together, making their own goods and growing their own food. It would be somewhere pleasant like the rolling landscapes of Italy, with local people to tend house and garden. (It’s unclear whether these local people would be liberated too.)

Intellectual criticisms

Greer’s celebration of non-monogamous sex in The Female Eunuch and her derision of Western society’s obsession with sex in Sex and Destiny led critics to label her ideas slipshod and too inconsistent for a public intellectual.

The root of most criticisms and controversies surrounding Greer, tend to stem from her view of the sexes. Like other second wave feminists, she suggested biological sex determined women’s oppression. This stands in stark contrast to the perspectives of third wave feminists and queer theorists, such as Judith Butler, for whom gender’s learned behaviours play the crucial role.

Greer and her contemporaries are often criticised by third and fourth wave feminists for predicating their philosophies on a male/female binary. A binary that does not account for the broad chromosomal spectrums found among intersex people or the many ways in which individuals feel and express their gender.

Infamous commentary

Greer is not the docile feminine woman she warned of in The Female Eunuch. She has long been celebrated for bucking trends and being refreshingly bold and frank. She is also heavily criticised for being rude, offensive and out of touch. She has been described as having “the self-awareness of a sweet potato”, a “misogynist”, and “a clever fool”.

After she extolled the work of Australia’s first female Prime Minister Julia Gillard on an episode of ABC’s Q&A, she was slammed for criticising Gillard’s body and clothing:

“What I want her to do is get rid of those bloody jackets … They don’t fit. Every time she turns around you’ve got that strange horizontal crease which means they cut too narrow in the hips. You’ve got a big arse Julia…”

Social media lit up with calls for Greer to “shut up” after she linked rape and bad sex in the age of #MeToo:

“Instead of thinking of rape as a spectacularly violent crime – and some rapes are – think about it as non-consensual, that is, bad sex. Sex where there is no communication, no tenderness, no mention of love. We used to talk about lovemaking.”

It is probably Greer’s public statements around transgender women that have attracted the most protest. In an interview after an intense no-platforming campaign to cancel a lecture Greer was scheduled to give at Cardiff University on women and power in the 20th century, she said, “Just because you lop off your penis and then wear a dress doesn’t make you a fucking woman”.

This sentiment probably links with Greer’s ideas on sexed bodies. A sympathetic reading of the comment might see it as one about being born into oppression – a rather second wave feminist sentiment that echoes the racial and queer politics of the same era. An idea that’s sometimes cited as analogous to Greer’s controversial comment is that you cannot understand what it is to be black, unless you were born black and experienced discriminations since the day of your birth. Perhaps she was suggesting we cannot understand the oppression experienced by women and girls unless we are born into a female body. Perhaps not. Either way, the comment was received as incredibly offensive and naive to transgender women’s experiences.

“People are hurtful to me all the time. Try being an old woman. I mean for goodness sake! People get hurt all the time. I’m not about to walk on eggshells.” – Germaine Greer, 2015

Greer and second wave feminists generally are at odds with intersectional feminism which is prominent today. Intersectional feminism holds that many factors beyond sex marginalise people – age, race, nationality, disability, class, faith, sexual orientation, gender identity… Different women will be oppressed to varying degrees.

Whether Greer is a trailblazer or tactless provocateur, it is doubtless her ideas have influenced the political and personal and landscapes of gender relations and feminist thinking.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccines: compulsory or conditional?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology