'Vice' movie is a wake up call for democracy

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

America has sold a unique brand of exceptionalism.

Some say no modern nation surpasses its military, economic, scientific and cultural prowess. Prominent Americans revere their country as an “empire of liberty”, a “shining city on a hill”, the “last best hope on Earth,” and the “leader of the free world”.

These enduring paeans are an apparent result of America’s political philosophy. By privileging individual freedom for every citizen, the American finds themselves in a unique position all of the time: whenever they choose to do something, they exercise a political right.

This choice has come to be sacred. Vice is about the lengths a self-proclaimed patriot will go to protect it.

When director Adam McKay’s film The Big Short earned him an Oscar for screenwriting, audiences discovered the former SNL comic’s hidden skill – turning concepts that usually made people feel bored or stupid, engaging and funny.

It’s our luck that after the tenth anniversary of 2008 financial crisis, and one month after George H. W. Bush’s funeral, his next target of irreverence would be the shadowy figure of Dick Cheney.

Far from a hagiography, Vice – carried seamlessly by an unrecognisable lead in Christian Bale and a cuttingly ambitious Amy Adams as his wife Lynne – seems an unambiguous condemnation of the Bush-Cheney administration, an ancestor of today’s American right.

This is no typical biopic.

There are no sweeping landscapes and sombre confessionals in red-curtained studios, nor any attempt to feign journalistic objectivity. No off-screen interviewer neatly ties the narrative together and the fourth wall is broken in the first ten minutes.

Absurdity, characters addressing the viewer directly, and thick visual metaphors give Viceits unique personality (wait till you see the scene with the heart). McKay wants you to know he is speaking directly to you. This isn’t a squared off paragraph confined to history books. It is what shaped our present.

Make no mistake: just because it’s opinionated doesn’t mean it isn’t well researched. McKay told the New York Times that the movie encompassed “five decades of Cheney’s life, 200 locations and more than 150 speaking parts”. According to him, a more measured, less confrontational tone wouldn’t have suited the OTT political circus we live in now. “Why be subtle anymore?”

While a conservative backlash is to be expected, this Cheney is no bloodless monster. He’s human. An idealist. His tender love for his daughters and unquestioning devotion to his wife are the same qualities that bond him to the bawdy Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell), and the ranks of a post-Watergate GOP.

He’s a creature of a slower, sweeter time: honed by long scenes of fly-fishing and the vast plains of Wyoming. McKay contrasts this with the energetic, M&M crunching Bush, played by a chameleon-like Sam Rockwell.

Cheney watches and waits. And watches and waits. He leaves no trace. And he is in it for the long haul.

At its core, Vice is a story about democracy. It is a warning that the halls of power rarely grant wishes without demanding a sacrifice, and too often this sacrifice begins with stripping the humanity of the powerless. It is about the special accomplishment of the individual who advances into public life when retreating into privacy is the easiest and most natural thing to do.

It is an admission that envy, chronic discontent and loneliness are intrinsic to democracy, but that its expansive collectivism are how to combat it. It’s all of this, and a demand to keep paying attention.

In his letters, Alexis de Tocqueville speaks of his ambition “to point out if possible to men what to do to escape tyranny and debasement in becoming democratic.”

Philosopher Alexandre Lefebvre offers the following:

“He [Tocqueville] seems to say that tyranny and debasement are part and parcel of becoming democratic. But… [it] works the other way around as well: that in becoming democratic – that is, in becoming properly democratic, democratic in the right way – we can hope to escape the new kinds of tyranny and debasement that democracy brings about…

For as Tocqueville exhorts himself in an unpublished note, we must “use Democracy to moderate Democracy. It is the only path open to salvation to us.”

McKay, and Cheney, would agree.

Vice is released in movie theatres 26 December 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 DEC 2018

Sometimes, good people do bad things. The last year confirmed this. Banks, schools, universities, the military, religious institutions – it seems 2018 left no sector unshaken.

These are the sorts of issues we confront every day at The Ethics Centre. In our reviews and confidential advice we have seen similar patterns repeat over and over again.

Yes, bad apples may exist, but we find ethical issues arise from bad cultures. And even our most trusted institutions, perhaps unwittingly, foster bad behaviour.

That’s why we have an important job. With your support we help society understand why ethical failures happen and provide safeguards lest they repeat.

As The Ethics Centre approaches its 30th birthday, we’d love to say we’re no longer needed. We hoped to bring ethics to the centre of everyday life and think we’ve made a small dent into that task. But there’s no point pretending there’s not a long way to go.

We thank you for supporting us and believing in us and are proud to share the highlights of another busy year with you.

If you’re short on time to read the full report now (and we’d really love you to take a look some time at what a small organisation like ours can achieve), here are seven highlights we’re particularly proud of:

• We launched The Ethics Alliance. A community of organisations unified by the desire to lead, inspire and shape the future of how we do business. In one year, 37 companies have benefited from the innovative tools that help staff at all levels make better decisions.

• We published a paper on public trust and the legitimacy of our institutions. Our conversations with regulators, investors, business leaders and community groups, revealed a sharp decline in the trust of our major institutions. We identify the agenda they need to in order to maintain public trust and contribute meaningfully to the common good.

• We ramped up Ethi-call. Calls to our free, independent, national helpline increased by 74 per cent this year. That’s even more people to benefit from impartial, private guidance from our highly trained ethical counsellors.

• We reviewed the culture of Australian cricket. When the ball-tampering scandal hit the world stage, Cricket Australia asked us to investigate. We uncovered a culture of ambition, arrogance, and control, where “winning at all costs” indicted administrators and players alike.

•We released a guide to designing ethical tech. Technology is transforming the way we experience reality. The need to make sure we don’t sacrifice ethics for growth is more pressing than ever. We propose eight principles to guide the development of all new technologies before they hit the market. You can download it here.

•We redesigned the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. FODI was created to facilitate courageous public conversation. The Ethics Centre and UNSW’s Centre for Ideas collaborated to untether the festival and produce a bold and necessary world-class cultural event. Every session sold out.

• We grew our tenth year of IQ2. We doubled the number of live attendees and tripled the student base showing audiences are more intelligent and hungry for diverse ideas than they are often given credit for. We welcomed a new sponsor Australian Ethical whose values align with our own. There’s never been a better time to support smart, civic, public debate.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Education is more than an employment outcome

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

Climate change. Nuclear war. Artificial intelligence. A new pandemic.

According to the non-profit organisation 80,000 Hours, these are the greatest threats to humanity today. Yet the big movie studios have been calling it for decades and were pondering the ethics behind these threats long ago.

1. Planet of the Apes (1968)

Seeing Charlie Heston scream in despair at a shattered Statue of Liberty still spooks the most apathetic viewer. And it’s as shocking a warning against nuclear weapons now as it was in the middle of the Cold War 50 years ago.

In Planet of the Apes, humans are being hunted. The primates they once experimented on have grown into intelligent, complex, political creatures. Humanity has regressed into primitive vermin to either be killed outright, enslaved, or used in scientific experiments. The strict ape hierarchy demands utility over compassion, holding a mirror up to the same vices that led humanity to destruction.

—————

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

When a survey of living computer science researchers shows half think there’s a greater than 50 percent chance of “high-level machine intelligence” – one that reaches then exceeds human capabilities – it’s right to be concerned.

2001: A Space Odyssey begins with a jaunty trip to Jupiter. An optimistic team is led aboard by HAL 9000, the ship’s computer, but begin to suspect there’s more to the trip than they’ve been told.

After all, there are two sides to the utilitarian coin. What is murder to us is just programming to a robot.

—————

3. The Matrix (1999)

If reality is a simulation by super intelligent sentient machines, what does any self-respecting hacker do? Start a rebellion.

The Matrix goes even further than 2001: A Space Odyssey. Here, the machines are Descartes’ evil demon, unsatisfied with just killing us. Instead, they mine us for energy to survive, and keep us subservient on a diet of virtual reality. A world of love, work, boring parties, and paying bills occupy us while they use us as slaves.

The point of tension in The Matrix centres around the theory of Plato’s Cave. If you know what everyone is experiencing is an illusion, should you tell them?

—————

4. 28 Days Later (2002)

28 Days Later paints a bleak picture of a world unprepared to deal with the effects of an aggressive pandemic. And it’s not as unbelievable as it may seem. According to 80,000 Hours, the money invested into pandemic research isn’t nearly as much as we need.

From HIV-AIDS, Ebola, and Zika, we’ve seen countries drag their feet over who pays to contain one, or struggle to move people and supplies to where they’re needed.

“When you’re in the middle of a crisis and you have to ask for money”, says Dr. Beth Cameron at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, “you’re already too late”.

—————

5. Children of Men (2006)

What is arguably more important than any of these things is hope. And that’s what our last movie recommendation is about.

After two decades of unexplained female infertility, war, and anarchy, human civilisation is on the brink of collapse. Civil servant Theo Faron has lost all hope as the last generation of his species. Then he meets Kee – an illegal immigrant and the first woman to be pregnant in eighteen years.

The hope for a better future, for a future that is more just and more compassionate, adds intangible meaning to our struggles today. It becomes reasonable to struggle, to suffer, and even to die for this kind of hope.

What makes the hope of today different is that we are now closer to “hypotheticals” than we have ever been.

Are we prepared to turn this hope into action? Effective altruism offers one way to find out.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

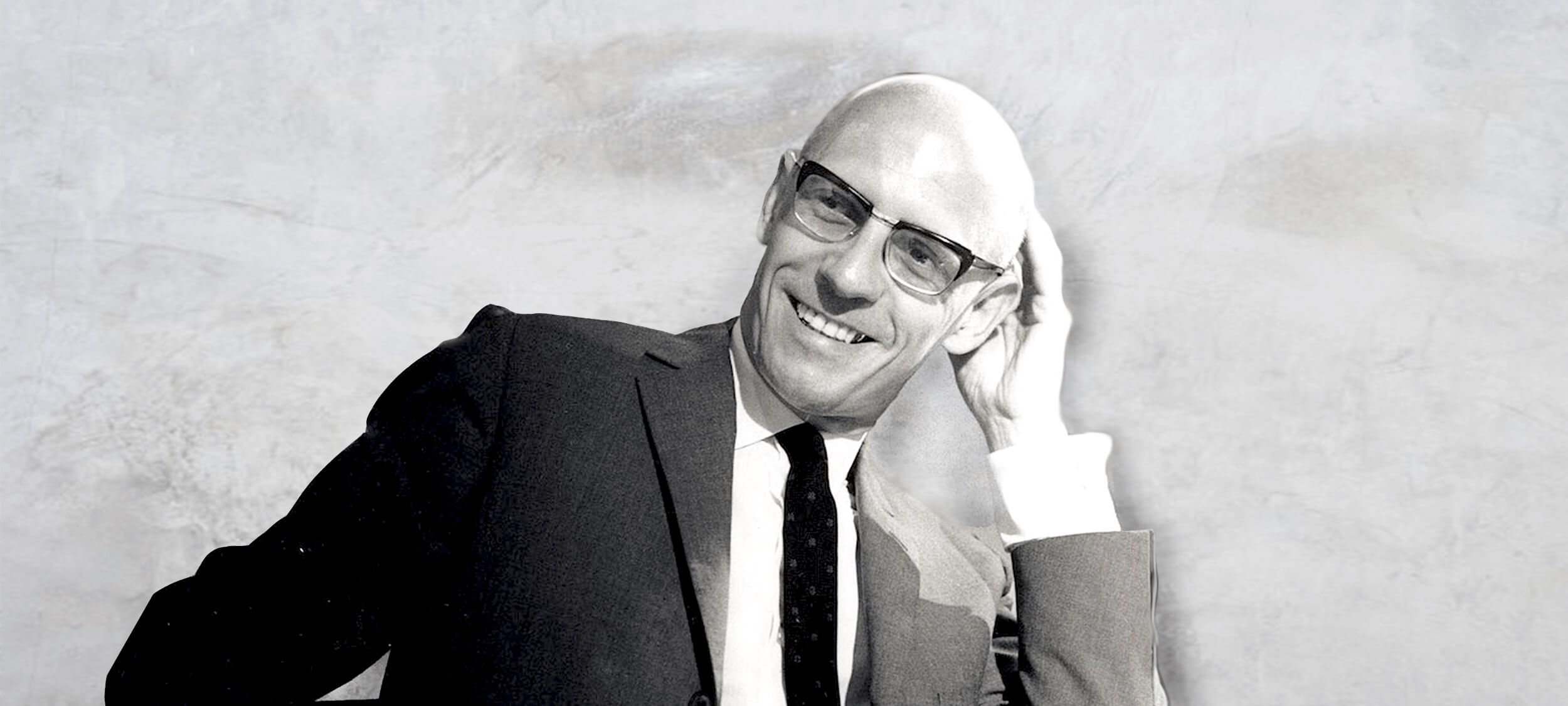

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships