A critical thinker’s guide to voting

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 14 APR 2025

In Australia, we have no formalised method of teaching people about politics, voting and elections. Most people vote the same way as their parents in their first elections, and won’t receive any more education beyond how-to-vote cards and electoral ads.

People under the age of 25 make up about 10% of all voters – that’s about ten thousand per electorate. They’re the most underrepresented group in political discourse and in elections. Not only that but young people will have to live with the consequences of these policies far longer than any other demographic.

Given that some elections come down to only a few hundred votes, the way we vote really does matter.

Our votes matter beyond the current election – they affect future elections too. The Australian Electoral Commission provides funding for every candidate or group that receives more than 4% of first preference votes. This means that even small groups can become big factors, influencing future elections and swaying the balance of power in parliament.

Finally, democracy works because it’s about communicating our needs and visions of the future. The major parties pay attention to how and why people vote. The Labor and Liberal parties have issues that they care about but others they overlook. A vote can shift the way the policy platforms of the major parties to discuss the issues we care about.

Here is a practical guide to critically think about your vote.

Step 1: Ignore the hype

Political parties are really good at demonising each other. They’ll accuse each other of being craven, lying, baby eating monsters. None of this is useful information. Almost every piece of political messaging from every party is propaganda designed to get your vote. They’ll frame the issues in terms of economics, jobs, the environment or tradition. This anchors our thinking in a way that is unhelpful for choosing a candidate, making it difficult to consider nuance and complexity.

Step 2: Value democratic integrity

Our democracy cannot function if our representatives are known liars, are demonstrably corrupt, or engage in unscrupulous mudslinging against other candidates. Everyone believes they are morally correct but if the candidate spends their time hurling insults, they’re actively toxic to our democracy. If the candidate is willing to say or do anything to get elected, they can’t be trusted to further the public good and should come last on the ballot.

Our democracy only functions if its processes are open, fair and honest. Recent changes to the ways political candidates are allowed to fundraise means that it may be easier for incumbents to stay in power, and harder for newcomers to challenge them. It’s worth looking into whether your member of parliament supported these changes, or aims for a level playing field.

Step 3: Think about your values

The most fundamental part of knowing who to vote for is knowing what your values are. There are an endless number of beliefs that we might hold. We might believe in universalism and benevolence (welfare for all, tolerance and understanding), which lead to policies like a universal basic income, investment in public broadcasters like the ABC, and increasing foreign aid. Values such as self-direction and achievement are more important to us (pursuing and gaining personal success) lead to policies that minimise taxation and deregulation. Voting against same-sex marriage or changes to the constitution to include First Peoples are examples of valuing tradition, whereas policies that block foreign investment or advocate turning back asylum seeker boats prioritise security.

There’s no such thing as ‘having bad values’, but it’s important to know what we believe, why we believe it, and prioritise these when it comes to elections. Ask yourself how important each of your principles and goals are in turn, and if your vote will move you further towards them.

Step 4: Think about what you’d like for the country

Now that you understand your values, think about how they inform the kind of country you want Australia to become. Political parties offer massive packages of policies containing aspects we agree with or may not like. Vote compasses can be useful at this point in this task – they have specific policy directions that allow us to precisely target what we would want to achieve in the country. This is an important step because we might agree with a party’s stated views but if their policies don’t match up, we’re not going to be represented well.

It’s common to agree with only part of a party’s political package. This is why we need to learn about all the candidates’ parties, their aims, and which best aligns with our own views. Preferential voting is a way of creating an order of best fit – with your number 1 preference going to the party that most aligns with your views, and each subsequent preference being the next best fit. The party that least represents your views should get your last preference.

Step 5: Learn about the parties

Labor and the Liberals are the most powerful and oldest parties in Australia. They aren’t exactly the same platforms as they once were, which is why second hand information from others may be out of date. The Greens are also a significant party and often hold the balance of power in the Legislative Assembly. There are many other parties that will be in your division and it’s worth looking into what they value and what their aim is specifically. There are many parties that focus on single issues that are important to them.

Step 6: Discover the candidates’ credentials and goals

The Australian Electoral Commission provides information about all currently enrolled candidates. Additionally, blogs like The Tally Room track candidates for each division and provide links to all of their personal websites.

A person’s qualifications and work history will tell us a bit about who someone is. Do they own a business? Ran a not-for-profit? Have they been a teacher or academic or front line retail worker? Have they been bankrupt? This is useful for telling us what kind of person we’re voting for and how they think.

Another important aspect is how clearly they’ve articulated their goals. Every party is in favour of good economic management, green technology and low unemployment figures. What matters is which they prioritise given the current context. It’s also worth considering what they plan in the long term – do they have a vision for Australia in 20 years? In 50? A party that only sees the future one electoral cycle ahead is one that will make short sighted decisions.

Lastly, if they can’t concisely say that they aim to enact a specific law or to increase a certain tax, we have reason to question their competence. A candidate can talk about the value of freedom all they want – without a stated goal, they either haven’t thought about it or they’re dog whistling.

Step 7: Judge the incumbent’s track record

The member of parliament for your division has a higher burden for gaining re-election because they have to defend their record. What have they done so far? What have they accomplished? How have they voted in the House of Representatives or Senate? Hansard is the official record of parliamentary speeches and votes. They Vote for You is a not-for-profit independent non-partisan organisation which tracks how the current member of parliament has voted (from Hansard). This includes their attendance (how often they do their job), and what they vote consistently for and against. This is particularly useful for us if we care about a specific issue – we can discover if the sitting member supports or votes against it in parliament.

A final thought

There are no wrong choices except those which are made with inaccurate information. This guide will take less than an hour and that’s not much to be conscientious about your vote once every three years. Democracy isn’t just about voting. It is in our civil discourse itself and how we share our perspectives.

Think about whether the status quo should stay the same or change based on your values and goals, then vote for the candidate that you believe represents your view. When you talk to people about who you’re voting for, be curious about their values and their perspective. From these together, you’ll have a thoughtful and well considered perspective.

This article has been updated since its original publication in 2022. Image by AEC photo.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Academia’s wicked problem

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 1 APR 2025

Political campaigns are mechanisms of persuasion – they aim to convince you to give them your vote.

However, they often use underhanded and bad faith tactics – not because they’re sneaky (though they can be) but because humans don’t naturally process and interpret information rationally.

This isn’t usually bad news for us – by thinking more quickly and reactively, we’re able to identify threats and safety immediately. But when it comes to elections, thinking logically is a different beast altogether. We have to slow down our thoughts, order information, make connections between ideas, discern truth from lies.

Political messaging relies on us using our simple thinking habits rather than the more rational process. Mean-spiritedness, name-calling, and catch-phrases are all tactics used to make us unconsciously lean towards or against voting for someone. Some strategies are deliberately designed to put us into specific emotional states – like anger or fear – to coax us into agreeing with the politician.

It’s more important now than ever that we recognise the tactics and strategies used so we can avoid being reactive and non-deliberative when voting. By slowing down our thinking – being more rational, and processing our emotions after we’ve examined a political message, we can come to the best possible decision come election time.

Here are some tactics that are often used, and tools that can help us combat them:

Branding and slogans

Slogans – especially catchy rhyming ones – make political messages easy and fast to understand. “Back on track” is being used by the Liberal Party in Australia this year, with “Building Australia’s Future” as the Labor party’s mantra. You might have heard an assortment of even simpler brands like “woke”, “groomer”, “degeneracy” or “traditional”.

These phrases are meant to be emotionally evocative and more importantly, be easily repeated. When scrolling social media, it’s far more likely that a person will absorb this idea unconsciously and feel a certain way. “Building Australia’s Future” evokes a sense of optimism in the audience. Similarly, “Australia Back on track” has an embedded sense of hope but also includes a slight sense of unease about the current system. Anxiety guides the thought – and it’s more likely that we won’t be thinking too deeply about which policies we agree with or what where we’d like the country to go.

At a minimum, branding and slogans don’t allow for nuanced conversations. Engagement goes up, but deep understanding goes down.

What you can do: Be mindful of your emotions

All political advertising is designed to make us feel a certain way. After reading or watching the content, check in with yourself. What are you feeling right now? Optimistic? Slightly anxious? Outraged? Recognise that the ad meant to evoke that and influence you.

Avoid taking the emotional bait. Try to avoid reacting and instead take a moment to consider why they’ve chosen that feeling for the ad. Positive emotions aim to build loyalty and trust, whereas negative emotions create a sense of urgency and amplify the downsides. Finally stay objective – consider what it is that’s factually true about this issue.

Priming

Priming is the practice of putting people in a certain frame of mind before discussing a political issue. For example, a common and volatile topic of debate is that of transgender people in sports. We often see public outcry at how unfair it is to have transgender women competing against cisgender women – transgender athletes are seen as having unfair biological advantages at best, or are ‘pretending’ to be women at worst – all just for a win.

This topic has been primed in a certain way – primed to lean on preexisting ideas of fairness and gender.

It’s reasonable to have strong feelings about what makes sports fair after all. But how would the conversation change if it started by talking about the bullying transgender people endure just for trying to play sports? What if the discussion started with the disproportionate mental health struggles they face compared to the wider population? This priming shifts the tenor of the entire conversation.

An argument that needs priming is one that is playing on our prejudices and biases – an obvious sign of a weak and unconvincing argument. Compelling ideas don’t need to rely on this kind of tactic to be persuasive.

What you can do: Reframe your thinking

After engaging with the material, take a moment to reflect. Are you being led to support a specific side? Are you valuing one piece of evidence more than another?

Avoid jumping to conclusions based on the presented viewpoint. Instead, ask yourself why the content is framing certain ideas favourably. Balanced content usually considers multiple perspectives while biased content steers you toward one.

Framing

Framing shapes how we see an issue, often making it seem overly simple or emotional. For example, the term ‘pro-life’ frames opponents as ‘anti-life,’ which is misleading. Abortion as a topic is filled with complex ideas around bodily autonomy, medical privacy, and beliefs around when life begins – framing this issue as simple removes all ability to explore it with any nuance.

Another way framing can be harmful is that it encourages feeling, rather than thinking. Fear of immigrants is a classic tactic used for hundreds if not thousands of years, and Australian politics is no different. Immigrants are depicted as a threat to jobs, culture and safety. The fear frame is meant to get people feeling like there’s an imminent danger when facts and common sense say otherwise.

What you can do: Deepen your thinking about the world and understanding of yourself

Consider whether you’re being encouraged to examine the complexities of an issue or merely agree with a simplified viewpoint. Recognise that interactions, such as liking or sharing or responding to a post, will amplify the original idea – even if you disagree with it.

Avoid simply nodding along. Instead, take the time to reflect on the broader implications, possible outcomes, and alternative perspectives. Be open to being wrong and ready to hear differing opinions.

Also consider whether you’re being pressured to conform to a single group, person, or ideology. “Us vs them” narratives rarely reflect our complexities as people or societies. Messages that simplify to that degree focus on our differences, rather than attending to our common problems.

No identity or belief system is infallible or beyond criticism – our own beliefs are our biggest blind spot. Embrace the diversity within yourself and others, acknowledging that multiple perspectives can coexist and contribute to a richer understanding of the world.

Image: Martin Berry / Alamy Stock Photo

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

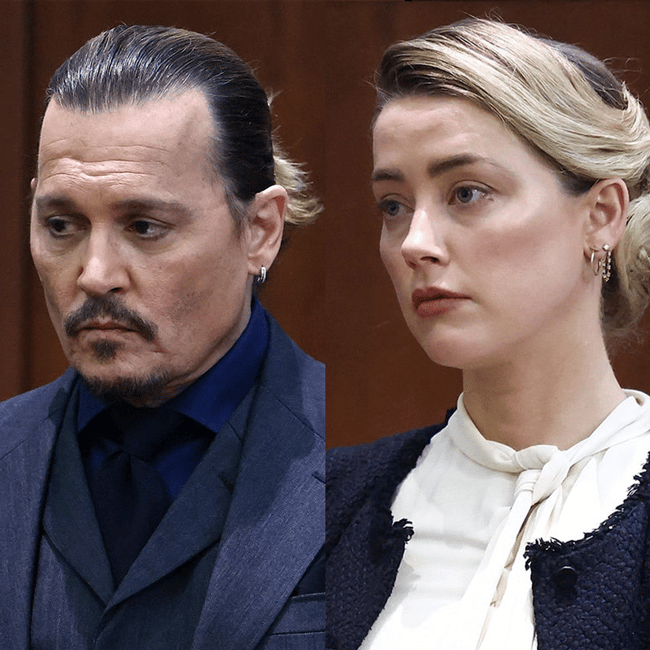

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Standing up against discrimination

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 3 FEB 2022

When the Prime Minister says classrooms shouldn’t be political and students should stay in school, that’s an implicit argument about what kinds of citizen he thinks we should have.

It’s not unreasonable. The type of citizen who has not gone out to protest will have certain habits and dispositions that are desirable. Hard-working, diligent, focused. However, the question about what it means to be a citizen and how to become one is complicated and not one that any one person has the truth about.

Let’s go back to basics though. What’s the point of education? It’s to prepare children for life. Many would claim it’s to get children ready for work, but if that was the case we would put them in training facilities rather than schools. Our education systems have many tasks – to make children work ready to be sure, but also to develop their personhood, to allow them to engage in society, to help them flourish. Every part of the curriculum, from its General Capabilities of critical and creative thinking to the discipline specific like technologies, is designed to provide young people with the skills, knowledge and dispositions necessary for being 21st century citizens.

What many don’t realise is that learning what it means to be a citizen isn’t localised to the curriculum. Interactions with parents, teachers, with each other, with news and social media – all of these contribute to the definition of a citizen.

Every time a politician says that children should be seen and not heard, that’s an indication of the type of citizen they want.

Most politicians don’t want kids out protesting after all – not only is it disruptive to whatever is in school that day, it looks really bad on the news for them. Protests are bad news for politicians in general and if children are involved, there’s no good way to spin it.

But we do want children to learn how to protest. We want them to be able to see corruption and have discussions and heated debates and embrace complexity. Everyone should have the ability to say their piece and be heard in a democracy. This is something that we’ve already recognised as persuasion is a major part of education and has been for years.

However, when we talk about this, we need to recognise that we aren’t just talking about skills or knowledge. This isn’t putting together a pithy response or clever tweet. It’s about being capable of contributing to public discourse, and for that, we need children to hold certain intellectual virtues and values.

An intellectual virtue refers to the way we approach inquiry. An intellectually virtuous citizen is someone who approaches problems and perspectives with open-mindedness, curiosity, honesty and resilience; they wish to know more about it and are truth seeking, unafraid of what terrors lie in it.

If virtues are about the willingness to engage in inquiry, intellectual values are the cognitive tools needed to do so effectively. It’s essential in conversation to be able to speak with coherence; an argument that doesn’t meaningfully connect ideas is one that is confusing at best, and manipulative at worst. If we’re not able to share our thoughts and display them clearly, we’re just shouting at each other.

Values and virtues are difficult to teach though. You can’t hold up flash cards and point to “fallibility” and say “okay, now remember that you can always be wrong”. We have cognitive biases that stand between us and accepting a virtue like “resilience to our own fallibility” – it feels bad to be wrong. The way we learn these habits of mind is through practice, through acceptance and agreement. Teachers, parents and adults can all develop these habits explicitly through classroom activities, and implicitly by modelling these behaviours themselves.

If a student can share their ideas without fear of being shut down by authority, they’ll develop greater clarity and coherence. They’ll be more open-minded about the ideas of others knowing they don’t have to defensively guard their beliefs.

To the original question of what it means to be a good citizen in a global context: we want our children to develop into conscientious adults. A good citizen is able to communicate their ideas and perspectives, and listen to the same from others. A good citizen can discern policy from platitude, and dilemmas from demagoguery.

But it takes practice and time. It takes new challenges and new contexts and new ideas to train these habits. We don’t have to teach students the logistics of organising a revolution or how to get elected.

And if we’re not teaching them when or why they should protest, we’re not teaching them to be good citizens at all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships