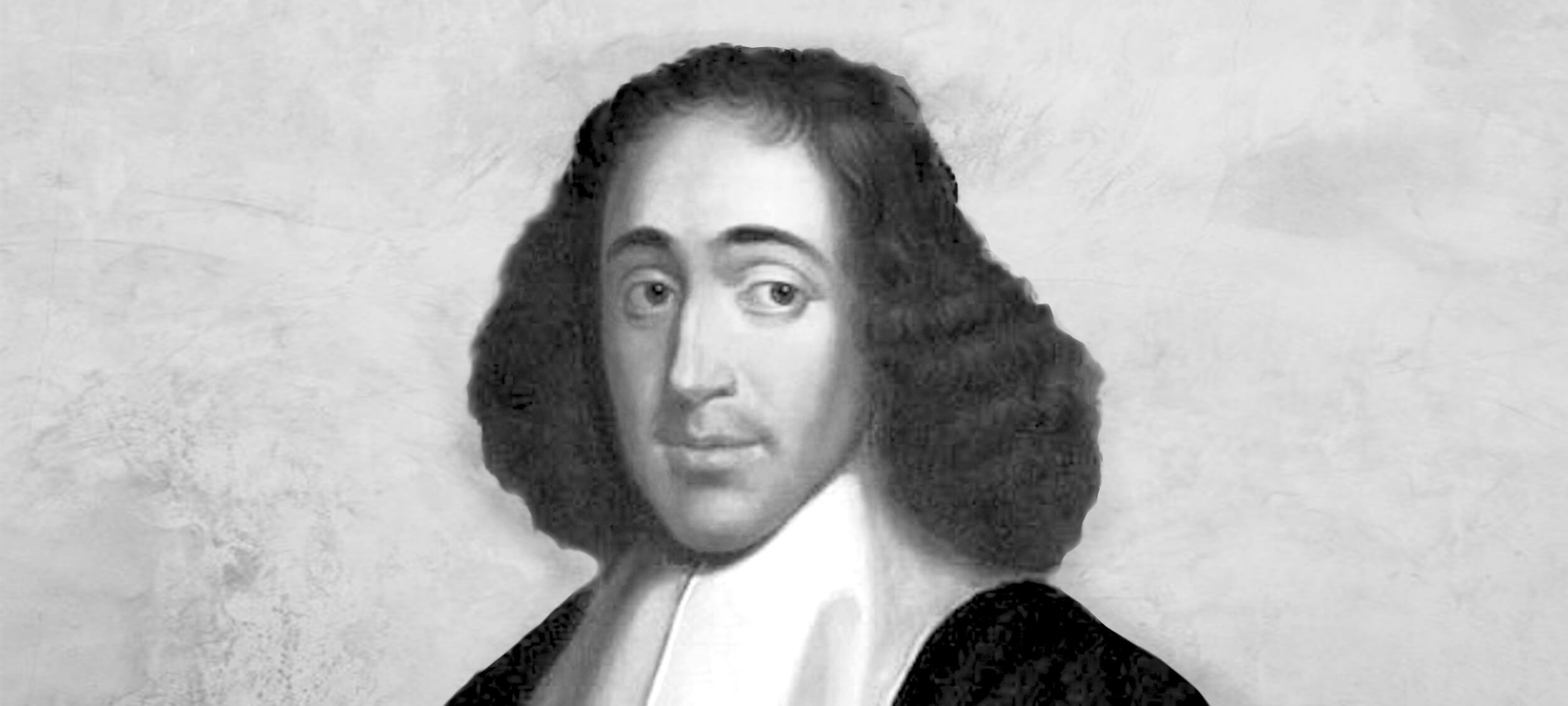

Baruch Spinoza was a 17th century Jewish-Dutch philosopher who developed a novel way to think about the relationship between God, nature, and ethics. He suggested they are all interconnected in a single animating force.

While Spinoza had a reputation for modesty, gentleness, and integrity, his ideas were considered heretical by religious authorities of the time. Despite excommunication by his own community and rabid denunciations from religious authorities, he remained steadfast to his philosophical outlook, and stands as an exemplar of intellectual courage in the face of personal crisis.

Jewish upbringing

Spinoza was born in 1632 in the thriving Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. His family were Sephardic Jews who fled Portugal in 1536, after being discovered practicing their religion in secret.

He was a studious and intelligent child and an active member of his synagogue. However, in his later teenage years, Spinoza began reading the philosophies of Rene Descartes and other early Enlightenment thinkers, which led to him to question certain aspects of his Jewish faith.

The problem with prayer

For the young Spinoza, prayer signified everything that was wrong with organised religion. The idea that an omnipotent being would listen to one’s prayers, take them into consideration, and then change the fabric of the universe to fit these individual desires was not only superstitious and irrational, but also underpinned by a type of delusional narcissism.

If there was any chance of living an ethical life, Spinoza reasoned, the first idea that would have to go was the belief in a transcendent God that listened to human concerns. This also meant renouncing the idea of the afterlife, admitting that the Old Testament was written by humans, and denouncing the possibility of any other type of divine intervention in the human world.

God-as-nature

Despite this, Spinoza was not an atheist. He believed there was still a place for God in the universe, not as a separate being who exists outside of the cosmos, but as a type of pervasive force that is inextricably bound up with everything inside it.

This is what Spinoza called “God-as-nature”, which suggests that all reality is identical with the divine and that everything in the universe composes an all-encompassing God. God, according to Spinoza, did not design and create the world, and then step outside of it, only to manipulate it every now and then through miracles. Rather, God was the world and everything in it.

Spinoza’s formulation of “God-as-nature” attracted many of the brightest minds of Europe of his time. The great German philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, visited Spinoza in Amsterdam to talk the theory over and concluded that Spinoza had a “strange metaphysics full of paradoxes. He thinks God and the world are one thing and that all created things are only modes of God.”

An ethical life of intellectual inquiry

Ultimately, Spinoza believed that replacing the idea of a transcendent God with “God-as-nature” was a step towards living a truly ethical life. If God was nature, then coming to know God was a process of learning about the world through study and observation. This pursuit, Spinoza reasoned, would draw people out of their narcissistic and delusional ways of understanding reality to a universal perspective that transcended individual concerns. This is what Spinoza called seeing things from the point of view of eternity rather than from the limited duration of one’s life.

For Spinoza, the ethical life was therefore the equivalent of an intellectual journey. He thought that learning about the world could lead a person towards understanding their connection to all other things. This, in turn, could lead one to see their interests as essentially intertwined with everything else. From such a perspective, the world no longer appears to be a hierarchy of competing individuals, but more like a web of interlocking interests.

Intellectual courage

These ideas got Spinoza into a lot of trouble. He was excommunicated from the Jewish community of Amsterdam when he was 23 and was considered by the Church to be an emissary of Satan. Nevertheless, he refused to compromise on his philosophical outlook and remained an outsider for the rest of his life. He eventually found refuge among a group of tolerant Christians in The Hague where he spent the rest of his life working as a lens grinder and private tutor.

A few months after his death in 1677, Spinoza’s philosophies were published as a collection called The Ethics. Its key ideas became very important for subsequent Enlightenment philosophers, who somewhat distorted his message to make them fit with their own radical atheism, despite his belief in “God-as-nature”.

Throughout the centuries, his ideas and life have continued to inspire not only philosophers but also scientists. Einstein wrote:

“I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”

In our current day, it is hard to fathom what made Spinoza’s ideas so radical. To equate the divine with nature or to talk about the cosmic interconnectedness of all things are more or less New Age platitudes. And yet, in Spinoza’s day, these ideas challenged not only an orthodox conception of God, but the entire social and political structure that depended on the transcendent authority of the divine order.

For this reason, studying Spinoza and his life not only provides an outline of ethics as an intellectual journey, but also demonstrates how much courage it takes to formulate and then hold steadfast to new ideas.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture