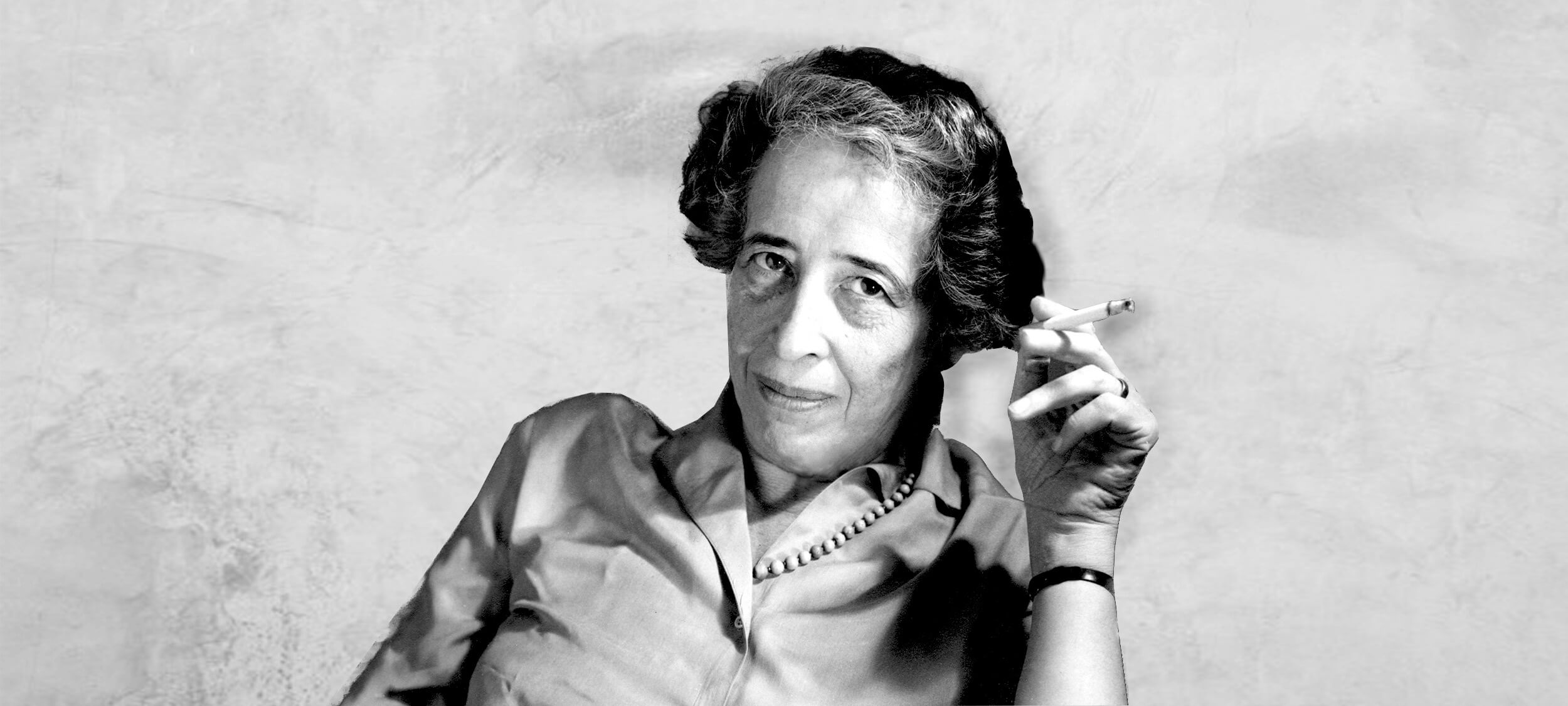

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades.

We are still learning from this seminal political theorist. Her book The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon in 2017, more than 60 years after it was first published.

Evil doesn’t need malicious intentions

Arendt’s most well known idea is “the banality of evil”. She explored this in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat who shared the first name of Hitler, Adolf Eichmann. This later became a book called Eichmann in Jerusalem: Reflections on the Banality of Evil.

In Eichmann, Arendt found a man whose greatest crime was a lack of thinking. His role was to transport Jewish people from German occupied areas to concentration camps in Poland. Eichmann did not kill anyone first hand. He was not involved in designing Hitler’s final solution. But he oversaw the trains that took millions of people to their deaths. They were gassed in chambers or died along the way or in camps due to starvation, overwork, illness, cold, heat, or brutality. Eichmann’s only defence for his involvement in this atrocity was obedience to the law and fulfilling his duty.

Eichmann was so steadfast with this line of reasoning he even referenced the philosopher Immanuel Kant and his theory of moral duty. Kant argued morality was acting on your obligations, not your emotions or what will bring you benefit. For Kant, the person who helps the beggar out of empathy or a belief assisting is a pathway to heaven is not doing an act of good. Kant felt everyone is morally obliged to help the beggar, and they are especially virtuous if they act on this duty despite feeling repulsed or no rewarding sense of doing good.

This does not really suit Eichmann’s argument because Kant was emphasising our ability to reason above emotion. This is precisely where Eichmann failed. We can only guess but it seems likely he did his job without asking questions while feeling a sense of comfort in the safety of his salary and senior position during volatile times.

Arendt believed it was this lack of true thinking and questioning that paved the way to genocide. Evil on the scale of Nazism required far more Adolf Eichmanns than Adolf Hitlers.

Totalitarianism needs political apathy

In studying the causes of WWII, Arendt came across “the masses”. She believed totalitarian regimes needed this to succeed.

By “the masses”, she meant the enormous group of people who are politically disconnected from other members of society. They don’t identify with a particular class, religion, or group. Their lack of group membership deprives them of common interests to demand from government. These people have no interest in politics because they don’t have political clout. They are an unorganised cohort with different, often conflicting desires whose needs are easily disregarded by politicians.

But although these people take no active interest in politics they still hold expectations for the state. If politicians fail those expectations they face “the loss of the silent consent and support of the unorganised masses”. In response, they “shed their apathy” and look for an outlet “to voice their new violent opposition”.

The totalitarian leader emerges from this “structureless mass of furious individuals”. With the political apathy of the masses turned to hostility, leaders will rise by breaking established norms and ignoring the way politics is usually done. Arendt dramatically says they prefer “methods which end in death rather than persuasion”. In short, they’re less likely to build politics up than they are to tear it down because that’s what the masses want.

If this all sounds depressing, there is a solution embedded in Arendt’s writing: political engagement. The masses arise when individuals are lonely and politically disconnected. They are defined by a lack of solidarity or responsibility with other citizens.

By revitalising our political community we can recreate what Arendt sees as good politics. This is when people feel a sense of personal and political responsibility for the nation and are able to band together with other citizens who have common interests. When citizens are connected in solidarity with one another, the mass never occurs and totalitarianism is held at bay.

When work defines you, unemployment is a curse

Not all Arendt’s work was concerned with war and totalitarianism. In The Human Condition, she also offers a general critique of modernity. Drawing on Karl Marx, Arendt thought the industrial age transformed humanity from thinkers into “working animals”.

She thought most people had come to define themselves by their work – reducing themselves to economic robots. Although it’s not a central point of Arendt’s analysis, this reduction is a product of the same forces she sees in the banality of evil. It’s a triumph of ‘doing’ over ‘thinking’ and of humans finding easy ways to define themselves.

Arendt wasn’t just concerned because people were reducing themselves to working drones. She also worried the industrial age which had just redefined them was also about to rob them of their new identities. She believed within a few decades, technology would replace factory jobs. Many people’s work would vanish.

“What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of labourers without labour, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.”

In a time when automation now threatens over half of jobs on average in OECD countries, Arendt’s predictions seem timely. Can we shift our identity away from work in time to survive the massive job reduction to come?

Published February 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights