Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard 17 SEP 2020

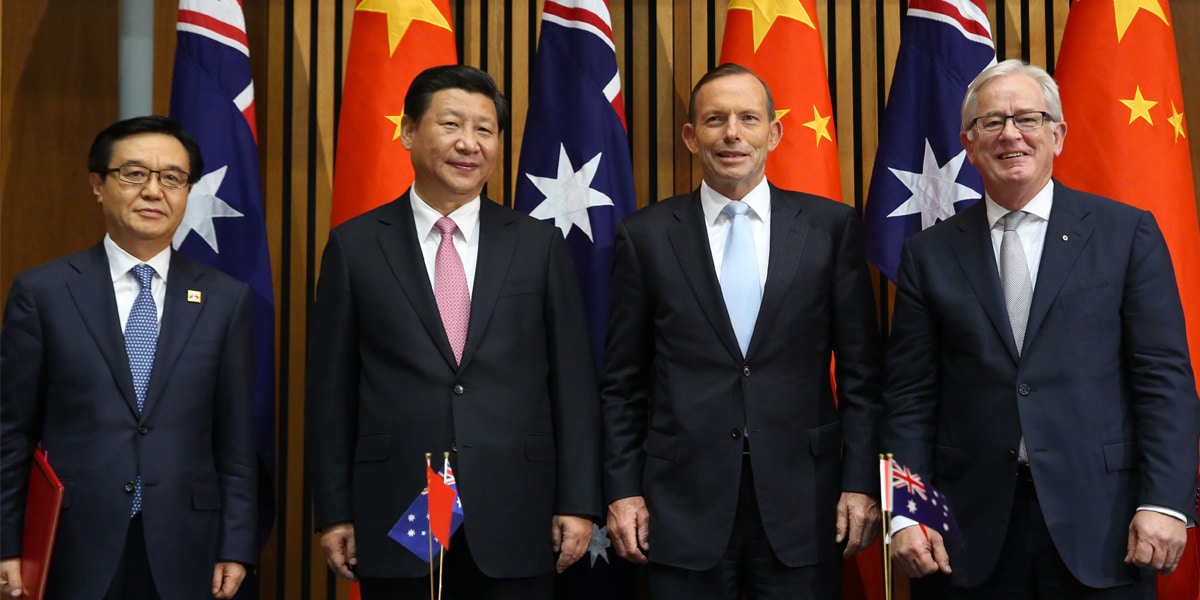

Former Aussie PM Tony Abbott’s recent appointment to an unpaid role as a trade adviser to the Johnson government in the UK has sparked controversy in both countries.

UK government MPs have continually been asked what it means to have a man who is, by the judgement of many in both countries, “a misogynist and a homophobe”, as well as a climate change denier and – more recently – sceptical about coronavirus lockdown measures.

In Australia, politicians, journalists and citizens have all questioned the appropriateness of a former Prime Minister accepting a position that leaves him serving a foreign government. Whilst Abbott has obligations under the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme that are designed to prevent conflicts of interest, there are many who believe Abbott is equipped with too much internal knowledge of Australia’s trade interests, internal party politics and regional issues in the Pacific – accrued as Prime Minister – for him to serve another government.

Given the range of questions that arise around both conflict and character, we made a list of some of the big ethical questions the Abbott situation brings up, and spoke to a few ethicists to help answer them.

1. Abbott is a private citizen now. Shouldn’t he be able to take any job he wants?

“Being Prime Minister isn’t like any other job,” says Hugh Breakey, a Senior Research Fellow at Griffith University’s Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law. “Abbott would have been privy to high level information and forward planning that he is obligated to hold secret.” If a potential employer of Abbott – whether in a paid role or not – would benefit from this situation, Breakey argues that it would give Abbott a conflict of interests.

But it’s not just a question of conflicts of interest. In situations like this, it is reasonable to consider whether this role was given as a “kind of payback for favourable treatment during his time in power,” Breakey says.

However, whilst Abbott’s appointment may generate potential conflicts of interest and are “legitimate lines of ethical inquiry”, Breakey believes they are not problems for Abbott’s appointment.

However, Simon Longstaff, executive director of The Ethics Centre, disagrees. “There just can be no guarantee that Britain’s interests will always coincide with Australia’s. Given this, the fact that one of our former Prime Ministers would ever serve a foreign power almost beggar’s belief,” he said.

2. If Abbott’s trade qualifications make him a good candidate, should we overlook his other beliefs and opinions?

“I believe that a representative of any country, in any honoured capacity like this one, should be a morally upstanding person. Tony Abbott is not that, given his history of misogyny, homophobia, and racism,” says Kate Manne, philosophy professor at Cornell University.

However, Hugh Breakey worries that an approach like this risks jeopardising our commitment to non-discrimination and supporting a diverse set of beliefs and ways of life. Sometimes, he says, ethics might require us to overlook the questionable beliefs of a potential political appointment.

“At least some of the views taken by Abbott on these matters have religious influences, and many similar (and, indeed, far more conservative) views are held by religious devotees across many of the world’s major faiths. Prohibiting from public offices and services all those who hold such views… would allow widespread religious discrimination.”

However, another complication arises when it comes to whose views and personality traits we tend to overlook. Cognitive biases, social norms and systemic beliefs like sexism and racism can mean we’re more likely to overlook controversial beliefs or difficult personalities when they belong to men, people who are straight or white.

Kate Manne suspects that “both women and non-binary people are far less likely to be viewed as truly qualified or competent, unless they’re also perceived as extraordinarily caring, kind, and what psychologists call ‘communal’.” She adds that the tendency to separate the professional and personal/political aspects of someone’s identity is “far less available to women and gender minorities.”

3. Should we label Abbott a misogynist or homophobe based only on his public comments and policies?

“The truth is, few people would know Tony Abbott well enough to say with any confidence what he truly feels or believes, and those who do know him paint a very different picture to the one sketched by his critics,” says Simon Longstaff. “A person can be opposed to same-sex marriage and yet not be a homophobe,” he adds.

However, for Kate Manne, the central question of misogyny or homophobia isn’t whether the person feels a certain way toward women or queer people, it’s what effect they have on those communities.

“Misogyny to me is not a personal failure or an individual belief system: it’s a system that polices and enforces a patriarchal order,” she says. “I define a misogynist in turn as someone who’s an ‘overachiever,’ or particularly active, in this system.”

Manne says, “misogyny on this view is less about what men like Abbott may or may not feel toward women, and more about what women face as a result of their toxic, obnoxious, and contemptuous behaviour.”

For Manne, this means Abbott can be reasonably called misogynist and homophobic on this basis. His status as a former PM and his very public comments have done considerable work to uphold a system that oppresses women and LGBTIQ+ people. She cites examples such as calling abortion the ‘easy way out’, standing next to a ‘ditch the witch’ sign or talking about feeling threatened by gay people as evidence of Abbott’s contributions.

4. How should we balance the need to reject some beliefs because they’re not morally acceptable or legitimate with our commitment to pluralism?

“Democracies gain critically in legitimacy by being able to conduct inclusive deliberations where diverse views can be raised and considered,” says Hugh Breakey.

“Naturally, no-one can or should expect immunity from social consequences for what they say in public discussion, Breakey adds. “The more that institutional sanctions are applied on the basis of positions taken in [controversial] debates the narrower the spectrum of positions that are likely to be defended, and the more that different views will fail to be represented.”

Kate Manne suggests a simple principle to test which voices we should accept as part of our political life: “It’s good to have a variety of voices, but those voices need not to silence or speak over the voices of other people,” she says.

“Abbott’s voice does not meet that simple test. “

Unlike Manne, Breakey doesn’t suggest Abbott’s views sit outside the realm of acceptable political opinions, he agrees with Manne’s principle. “If we want democracy to be more than the tyranny of the majority, or (worse still) rule by elites, then we need more civic tolerance afforded to those who think and speak in disagreeable ways.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights