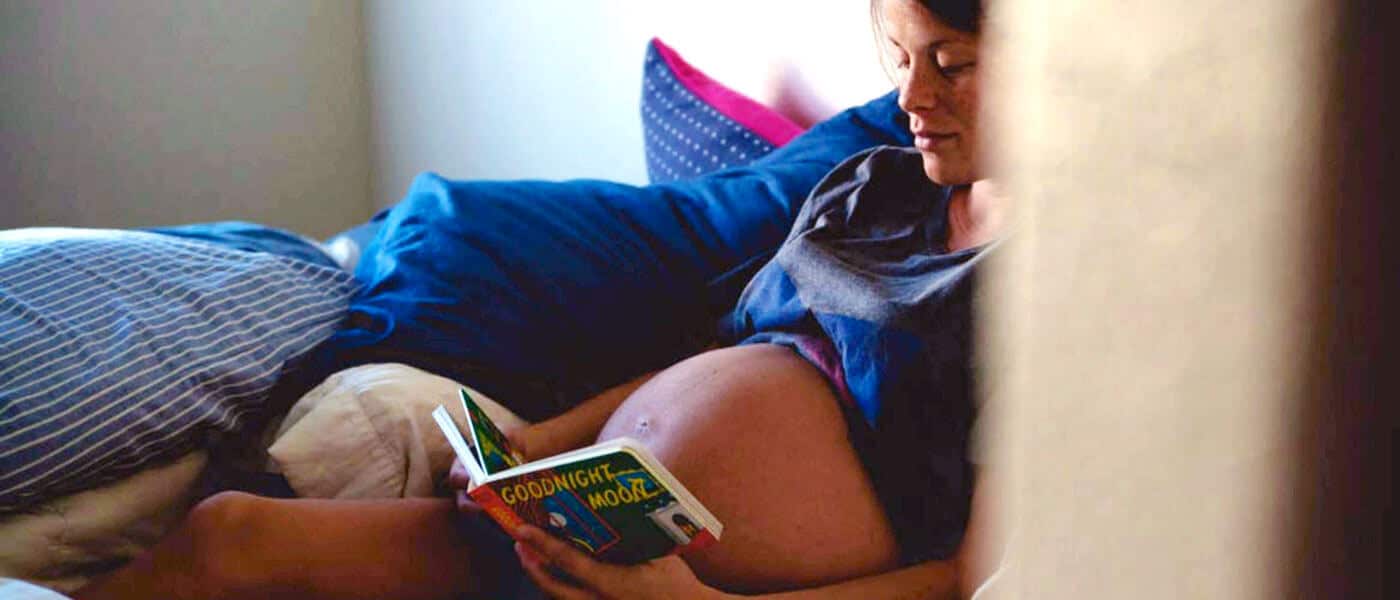

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Hannah Dahlen The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2016

Just try mentioning ‘birth plans’ at a party and see what happens. Hannah Dahlen – a midwife’s perspective

Mia Freedman once wrote about a woman who asked what her plan was for her placenta. Freedman felt birth plans were “most useful when you set them on fire and use them to toast marshmallows”. She labelled people who make these plans as “birthzillas” more interested in birth than having a baby.

In response, Tara Moss argued:

The majority of Australian women choose to birth in hospital and all hospitals do not have the same protocols. It is easy to imagine they would, but they don’t, not from state to state and not even from hospital to hospital in the same city. Even individual health practitioners in the same facility sometimes do not follow the same protocols.

The debate

Why the controversy over a woman and her partner writing down what they would like to have done or not done during their birth? The debate seems not to be about the birth plan itself, but the issue of women taking control and ownership of their births and what happens to their bodies.

Some oppose birth plans on the basis that all experts should be trusted to have the best interests of both mother and baby in mind at all times. Others trust the mother as the person most concerned for her baby and believe women have the right to determine what happens to their bodies during this intimate, individual, and significant life event.

As a midwife of some 26 years, I wish we didn’t need birth plans. I wish our maternity system provided women with continuity of care so by the time a woman gave birth her care provider would fully know and support her well-informed wishes. Unfortunately, most women do not have access to continuity of care. They deal with shift changes, colliding philosophical frameworks, busy maternity units, and varying levels of skill and commitment from staff.

There are so many examples of interventions that are routine in maternity care but lack evidence they are necessary or are outright harmful. These include immediate clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord at birth, episiotomy, continuous electronic foetal monitoring, labouring or giving birth laying down and unnecessary caesareans. Other deeply personal choices such as the use of immersion in water for labour and birth or having a natural birth of the placenta are often not presented as options, or are refused when requested.

The birth plan is a chance to raise and discuss your wishes with your healthcare provider. It provides insight into areas of further conversation before labour begins.

I once had a woman make three birth plans when she found out her baby was in a breech presentation at 36 weeks. One for a vaginal breech birth, one for a cesarean, and one for a normal birth if the baby turned. The baby turned and the first two plans were ditched. But she had been through each scenario and carved out what was important for her.

Bashi Hazard – a legal perspective

Birth plans were introduced in the 1980s by childbirth educators to help women shape their preferences in labour and to communicate with their care providers. Women say preparing birth plans increases their knowledge and ability to make informed choices, empowers them, and promotes their sense of safety during childbirth. Some (including in Australia) report that their carefully laid plans are dismissed, overlooked, or ignored.

There appears to be some confusion about the legal status or standing of birth plans. Neither is reflective of international human rights principles or domestic law. The right to informed consent is a fundamental principle of medical ethics and human rights law and is particularly relevant to the provision of medical treatment. In addition, our common law starts from the premise that every human body is inviolate and cannot be subject to medical treatment without autonomous, informed consent.

Pregnant women are no exception to this human rights principle nor to the common law.

If you start from this legal and human rights premise, the authoritative status of a birth plan is very clear. It is the closest expression of informed consent that a woman can offer her caregiver prior to commencing labour. This is not to say she cannot change her mind but it is the premise from which treatment during labour or birth should begin.

Once you accept that a woman has the right to stipulate the terms of her treatment, the focus turns to any hostility and pushback from care providers to the preferences a woman has the right to assert in relation to her care.

Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this.

Care providers who understand the significance of the human and legal right to informed consent begin discussing a woman’s options in labour and birth with her as early as the first antenatal visit. These discussions are used to advise, inform, and obtain an understanding of the woman’s preferences in the event of various contingencies. They build the trust needed to allow the care provider to safely and respectfully support the woman through pregnancy and childbirth. Such discussions are the cornerstone of woman-centred maternity healthcare.

Human Rights in Childbirth

Reports received by Human Rights in Childbirth indicate that care provider pushback and hostility towards birth plans occurs most in facilities with fragmented care or where policies are elevated over women’s individual needs. Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this. If anything, greater planning would facilitate smoother outcomes in the event of unanticipated eventualities.

In truth, it is not the case that these care providers don’t have a birth plan. There is a birth plan – one driven purely by care providers and hospital protocols without discussion with the woman. This offends the legal and human rights of the woman concerned and has been identified as a systemic form of abuse and disrespect in childbirth, and as a subset of violence against women.

It is essential that women discuss and develop a birth plan with their care providers from the very first appointment. This is a precious opportunity to ascertain your care provider’s commitment to recognising and supporting your individual and diverse needs.

Gauge your care provider’s attitude to your questions as well as their responses. Expect to repeat those discussions until you are confident that your preferences will be supported. Be wary of care providers who are dismissive, vague or non-responsive. Most importantly, switch care providers if you have any concerns. The law is on your side. Use it.

Making a birth plan – some practical tips

- Talk it through with your lead care provider. They can discuss your plans and make sure you understand the implications of your choices.

- Make sure your support network know your plan so they can communicate your wishes.

- Attending antenatal classes will help you feel more informed. You’ll discover what is available and the evidence is behind your different options.

- Talk to other women about what has worked well for them, but remember your needs might be different.

- Remember you can change your mind at any point in the labour and birth. What you say is final, regardless of what the plan says.

- Try not to be adversarial in your language – you want people working with you, not against you. End the plan with something like “Thank you so much for helping make our birth special”.

- Stick to the important stuff.

Some tips on the specific content of your birth plan are available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights