Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 MAR 2019

It was not that long ago that publicly disagreeing with your employer’s business strategy or staging a protest without the protection of a union, would have been a sackable offence.

But not today – if you are among the business “elite”.

Last year, 4,000 Google employees signed a letter of protest about an artificial intelligence project with the Department of Defense. Google agreed not to renew the contract. No-one was fired.

Also at Google, employees won concessions after 20,000 of them walked out protesting the company’s handling of sexual harassment cases. Everyone kept their jobs.

Consulting firms Deloitte and McKinsey & Company and Microsoft have come under pressure from employees to end their work with the US Department of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), because of concerns about the separation of children from their illegal immigrant parents.

Amazon workers demanded the company stop selling its Rekognition facial recognition software to law enforcement.

Examples like these show that collective action at work can still take place, despite the decline of unionism, if the employees are considered valuable enough and the employer cares about its social standing.

The power shift

Charles Wookey, CEO of not-for-profit organisation A Blueprint for Better Business says workers in these kinds of protests have “significant agency”.

“Coders and other technology specialists can demand high pay and have some power, as they hold skills in which the demand far outstrips the supply,” he told CEO Magazine.

Individual protesters and whistle-blowers, however, do not enjoy the same freedom to protest. Without a mass of colleagues behind them, they can face legal sanction or be fired for violating the company’s code of conduct – as was Google engineer James Damore when he wrote a memo criticising the company’s affirmative action policies in 2017.

Head of Society and Innovation at the World Economic Forum, Nicholas Davis, says technology has enabled employees to organise via message boards and email.

“These factors have empowered employee activism, organisation and, indeed, massive walkouts –not just around tech, by the way, but around gender and about rights and values in other areas,” he said at a forum for The Ethics Alliance in March.

Change coming from within

Davis, a former lawyer from Sydney, now based in Geneva, says even companies with stellar reputations in human rights, such as Salesforce, can face protests from within – in this case, also due to its work with ICE.

“There were protesters at [Salesforce annual conference] Dreamforce saying: ‘Guys, you’re providing your technology to customs and border control to separate kids from their parents?,” he said.

Staff engagement and transparency

Salesforce responded by creating Silicon Valley’s first-ever Office of Ethical and Humane Use of Technology as a vehicle to engage employees and stakeholders.

“I think the most important thing is to treat it as an opportunity for employee engagement,” says Davis, adding that listening to employee concerns is a large part of dealing with these clashes.

“Ninety per cent of the problem was not [what they were doing] so much as the lack of response to employee concerns,” he says. Employers should talk about why the company is doing the work in question and respond promptly.

“After 72 hours, people think you are not taking this seriously and they say ‘I can get another job, you know’, start tweeting, contact someone in the ABC, the story is out and then suddenly there is a different crisis conversation.”

Davis says it is difficult to have a conversation about corporate social activism in Australia, where business leaders say they are getting resistance from shareholders.

“There’s a lot more space to talk about, debate, and being politically engaged as a management and leadership team on these issues. And there is a wider variety of ability to invest and partner on these topics than I perceive in Australia,” says Davis, who is also an adjunct professor with Swinburne University’s Institute for Social Innovation.

“It’s not an issue of courage. I think it’s an issue with openness and demand and shifting culture in those markets. This is a hard conversation to have in Australia. It seems more structurally difficult,” he says.

“From where I stand, Australia has far greater fractures in terms of the distance between the public, private and civil society sectors than any other country I work in regularly. The levels of distrust here in this country are far higher than average globally, which makes for huge challenges if we are to have productive conversations across sectors.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

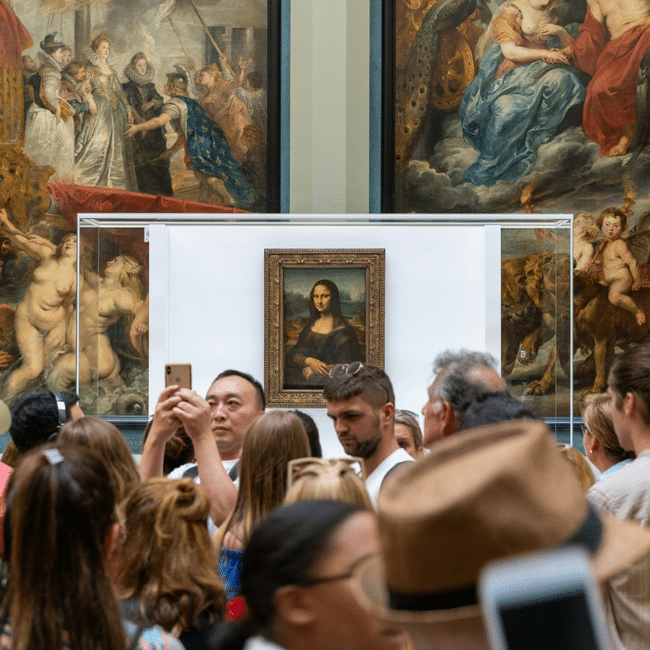

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP