How far should you go for what you believe in?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Cameryn Cass 28 MAR 2023

Do we all have a right to protest? And does it count if it doesn’t result in radical change? Grappling with its many faces and forms, philosopher Dr Tim Dean, and human rights lawyer and chair of Amnesty International UK, Dr Senthorun (Sen) Raj unpack what it means to ethically protest in our modern society.

In the wake of 2023 World Pride and Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, Raj and Dean reflect on a fundamental question present in all protest: What is it you’re protesting?

The first challenge is in agreeing on what the problem is: Is it freedom we’re fighting for? Equal rights? Sustainability? From there, you’ve got to expose the fault to enough people who are motivated to join in on the resistance.

“We can hope for a better future, but is it enough to just hope?” – Sen Raj

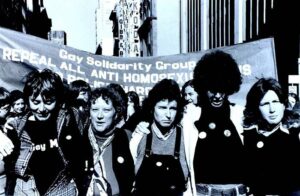

Even if a protest is small in numbers, it can be lasting in impact; just consider Sydney’s first Mardi Gras. It was a relatively modest event that’s now grown to nearly 12,500 marchers and 300,000 spectators. But it began with a fraction of those numbers. Late in the evening on 24 June 1978, a group marched toward Hyde Park with a small stereo system and banners decorating the back of a single flat-bed truck, like a scaled-down parade float. The march intentionally coincided with anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall riots, which remains a symbol of resistance and solidarity among the gay and lesbian community. As the night progressed, police confiscated the truck and sound system. Eventually, 53 people were charged – despite having a permit to march – after they fought back in response to the police violence. To this, Ken Davis, who helped lead the march, said, “The police attack made us more determined to run Mardi Gras the next year.”

“Protest” has multiple meanings

A meaningful protest doesn’t have to be major like Mardi Gras. Sometimes, protests by brave individuals alone have extraordinary impacts.

Thích Quảng Đức, a Mahayana Buddhist monk, famously burned himself to death at a busy intersection in Vietnam on 11 June 1963. In the height of the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam, Quảng Đức performed this self-immolation to protest Buddhist persecution. The harrowing photo of him calmly seated while burning alive touched all corners of the globe and inspired similar acts of sacrifice in the name of religious freedom.

Protests need not be so drastic, though, to have an impact. On 16 December 1965, a group of American students protested the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands with peace signs on them to school. When administrators told the students to remove the bands and they refused, they were sent home. Backed by their families, the Iowa school’s barring of student protest reached the Supreme Court. The famed Tinker v. Des Moines decision held that students don’t “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Tinker case is proof that protests, no matter how minor, can give rise to reformation. But we shouldn’t enter all protests with an expectation of radical change. Dean and Raj agree the assumption that transformation is the mark of a successful protest ought to be re-examined, as a clear outcome isn’t the only metric of success. As Raj said, “There is a tendency at times to assume that a protest will have a very clear message – a defined endpoint or outcome.”

Though progress might prove slow, it’s progress, nonetheless. We should act with the intention of spreading a message and entering a larger conversation that may or may not modify the status quo. Does a protest count for nothing if it doesn’t result in sweeping change? Is it not enough to ignite the spirit of defiance in just one soul? Or to simply express your authentic self even if it has no impact?

“For me, being queer, being trans, being part of a community that is marginalised and stigmatised for who you are or what you do, in itself, is a form of protest.” – Sen Raj

For members of the LGBTQIA+ community, Raj highlights how, “by virtue of existing, these individuals are being policed.” He says, “For me, being queer, being trans, being part of a community that is marginalised and stigmatised for who you are or what you do, in itself, is a form of protest.” So by refusing to conform and loving who they want, not holding themselves to gender or sexual norms, LGBTQIA+ people protest every day. It’s not a large mass gathering, but it’s a kind of protest, nonetheless. Authentic expression begets liberation; we ought not trivialise the importance of any protest, big or small, as it takes real courage to take part in something larger than yourself.

Does violence have a place in protests?

Just as protests can manifest in many forms, they can also be carried out differently.

Because tragedy and injustice are what usually catalyse protests, they’re often charged with strong – and sometimes overwhelmingly negative – emotions. It’s no surprise, then, that some protests turn violent.

But is violence ever permissible in a protest? And if police instigate it, do protesters have a right to protect themselves?

During the racial tensions in 1960s America, many protests ended in violence, especially by police. Images capture the savage behaviour in Birmingham, Alabama, where police unleashed high-powered hoses and dogs on Black protesters. In spite of such violence, they had no space to defend themselves; fighting back meant certain arrest. As Dean and Raj detailed in the discussion, sometimes authorities use this tendency towards self-defence to provoke violence and thus justify further oppression. Race riots persist in America as the fight against systematic racism and police brutality continues. The Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), founded in 2013 and popularised after a policeman wrongfully killed George Floyd in 2020, continues the fight for Black rights.

The fragility of protesting

The right to protest isn’t guaranteed and must be protected. In the absence of protest, the government and other institutions could operate unchallenged.

In Hong Kong, China enacted a new national security law in 2020 that’s a major barrier to protesting. Already, hundreds of protesters have been arrested. On paper, the law protects against terrorism and subversion, but in practice, it criminalises dissent. In the absence of protest, the powerful can ignore and silence the concerns of the masses. If a system is broken, binding together and protesting is an essential step in fixing it. Without protests, a broken system will remain broken.

“That’s what gives rise to protests, is that refusal. That refusal to allow for social or political worlds that oppress you to continue unchecked, and to say ‘Enough’.” – Sen Raj

Anti-protest laws aren’t a uniquely Hong Kong phenomenon. In April 2022, the New South Wales government passed more stringent legislation that punishes both protests and protesters that illegally dissent on public land. By blocking protests that prevent economic activity, critics say it’s an extremely undemocratic measure and threatens protests at large. Plus, it creates a hierarchy among protests, where some are viewed as valid while others aren’t. This raises the larger question of whether it’s the government’s place to determine which protests should be allowed. Does asking permission to protest do an injustice to the demonstration?

A way forward

It’s important to note that there’s no one way to protest. The textbook protest of a group of angry, fed-up citizens waving signs and shouting in the streets doesn’t always hold true. And so we’ve got to remember that protest need not look a certain way or foster radical change to be successful. It need not be a grandiose display of floats and intricate costumes parading down Oxford Street, like today’s Mardi Gras; sometimes it’s enough for one person to speak their mind.

Raj reminds us that protest ought to be messy, joyous and painful but should include care, respect and solidarity. He encourages us to abandon the stereotypical depiction of protest and embrace the possibility of many protests. It’s limiting to try and definitively define what it means. “Protest” is encapsulating of so many movements, minor and mammoth. Instead of trying to box it into one definition, let’s find beauty in its vastness.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Politics + Human Rights

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights