Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2024

In 2001, Marcellus Williams was convicted of killing Felicia Gayle, found stabbed to death in her home in 1998.

Over two decades later, he was given the death penalty, directly against the wishes of the prosecutor, the jury and, notably, Gayle’s family.

Cases like this draw our attention to the nature of punishment and its role in delivering justice. We can think about justice, and hence what is just punishment, as a question about what we deserve. But who decides what we deserve, and on what basis?

There are many ways that people think about punishment, but generally it’s justified in some variation of the following: retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and/or restoration. These are not all mutually exclusive ideas either, but rather different arguments about what should be the primary purpose and mode of punishment

Purposeful Punishment

Punishment is often viewed through the lens of retribution, where wrongdoers are punished in proportion to their offenses. The concept of retributive justice is grounded in the idea that punishment restores balance in society by making offenders ‘pay’ in various ways, like prison time or fines, for their transgressions.

This perspective is somewhat intuitive for most people, as it’s reflected in our moral psychology. When we feel wronged, we often become outraged. Outrage is a moral emotion that often inspires thoughts of harming the wrongdoer, so retributive punishment can feel intuitively justified for many. And while it has roots in our evolutionary psychology, it can also be a harmful disposition to have in a modern context.

The 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant strongly defended retributive justice as a matter of principle, much like his general deontological moral convictions. Kant believed that people who commit crimes deserve to be punished simply because they have done wrong, irrespective of whether it leads to positive social outcomes. In his view, punishment must fit the crime, upholding the dignity of the law and ensuring that justice is served.

However, there are many modern critics of retributivism. Some argue that focusing solely on punishment in a retributive way overlooks the possibility of rehabilitation and societal reintegration. These criticisms often come from a consequentialist approach, focusing on how to create positive outcomes.

One of these is an ongoing ethical debate about the role of punishment as a deterrent. This is a consequentialist perspective that suggests punishment should aim to maximise social benefits by deterring future crimes. This view is often criticised because of its implications on proportionality. If punishment is used primarily as a deterrent, there is a high risk that people will be punished more harshly than their crimes warrant, merely to serve as an example. This approach can conflict with principles of fairness and proportionality that are central to most conceptions of justice. Some also consider it to be a view that misunderstands the motives and conditions that surround and cause common crime.

Other, more contemporary, consequentialist views on punishment focus on rehabilitation and restoration. Feminist philosophers, such as Martha Nussbaum, have proposed a broader, more compassionate view of justice that emphasises human dignity. Nussbaum suggests that a purely punitive system dehumanises offenders, treating them merely as vessels for punishment rather than as individuals with the capacity for moral growth and change.

They argue that this dehumanisation is a primary factor in high rates of recidivism, as it perpetuates the cycle of disadvantage that often underpins crime. Hence, an ability for change and reintegration is seen by some as crucial to developing pro-social methods of justice that decrease recidivism.

Importantly, these views are not inherently at odds with traditional punishment, like prison. However, they are critical of the way that punishment is enacted. To be in line with rehabilitative methods, prisons in most countries worldwide would need to see a significant shift towards models that respect the dignity of prisoners through higher quality amenities, vocations, education, exercise and social opportunities.

One unintuitive and hence potentially difficult aspect of these consequentialist perspectives is that in some cases punishment will be deemed altogether unnecessary. For example, if a wrongdoer is found to be impaired significantly by mental illness (e.g. dementia) to the extent that they have no memory or awareness of their wrongdoing, some would claim that any type of retributive punishment is wrong, as it serves no purpose aside from satisfying outrage. This can be a difficult outcome to accept for those who see punishment as needing to “even the scales”.

Justice and Punishment

The ethical implications of punishment become even more complex when considering factors like bias and the reality of disproportionate sentencing. For example, marginalised groups face more scrutiny and harsher sentences for similar crimes, both in Australia and globally. This disparity is often unconscious, resulting in a denial of responsibility at many steps in the system and a resistance to progress.

If punishment is disproportionately applied to disadvantaged groups, then it is not just. The ethical demand of justice is for equal treatment, where punishment reflects the crime, not the social status or identity of the offender.

Whether our idea of punishment involves revenge or benevolence, it’s important to understand the motivations behind our convictions. All the sides of the punishment spectrum speak to different intuitions we hold, but whether we are steadfast in our right to get even, or we believe an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind, we must be prepared to find the nuance for the betterment of us all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

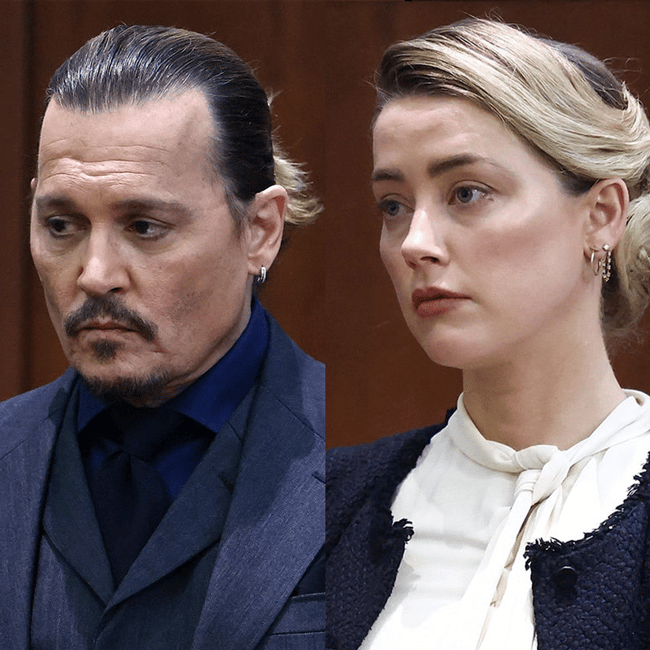

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights