People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kate Prendergast 24 APR 2019

It began in Oakden. Or, it began with the implosion of one of the most monstrously run aged care facilities in Australia, as tales of abuse and neglect finally came to light.

That was May 2017. Two years on, we are in the midst of the first Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, announced following a recommendation by the Scott Morrison government.

The first hearings began this year in Oakland’s city of Adelaide. They have seen countless brave witnesses come forward to share their experiences of what it’s like to live within the aged care system or see a loved one deteriorate or die – sometimes peacefully, sometimes painfully – within it.

In May, the third hearing round will take place in Sydney. This round will hear from people in residential aged care, with a focus on people living with dementia – who make up over 50 percent of residents in these facilities.

With our burgeoning ageing population, the number of people being diagnosed with dementia is expected to increase to 318 people per day by 2025 and more than 650 people by 2056.

Encompassing a range of different illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and Lewy body disease, its symptoms are particularly cruel, dissolving intellect, memory and identity. In essence, dementia describes the gradual estrangement of a person from themselves – and from everyone who knew them.

It is one of the most prevalent health problems affecting developed nations today – and one of the most feared. Contrary to widespread belief, one in 15 sufferers are in their thirties, forties and fifties.

Physical restraints

How do you manage these incurable conditions? How can you humanely care for the remnants of a person who becomes more and more unrecognisable?

One thing the Royal Commission has made clear: you don’t do it by defaulting to dehumanising mechanisms of restraint.

Unlike in the UK or the US, there are currently no regulations around use of restraints in aged care facilities. It is commonly resorted to by aged care workers if a patient displays physical aggression, or is a danger to themselves or others.

Yet it is also used in order to manage patients perceived as unruly in chronically understaffed facilities, when the risk of leaving them unsupervised is seen to be greater than the cost of depriving them their free movement and self-esteem. The problem of how to minimise harm in these conditions is an ongoing and high-pressure dilemma for staff.

Readers may remember the distressing footage from January’s 7.30 Report, in which dementia patients were seen sedated and strapped to chairs. One of them was the 72-year-old Terry Reeves. Following acts of aggression towards a male nurse, he was restrained for a total of 14 hours in a single day. His wife, however, had authorised that her husband be restrained with a lap belt if he was “a danger to himself or others”.

Maree McCabe, director of Dementia Australia, is vocal about why physical restraints should only be used as a last resort.

“We know from the research that physical restraint overall shows that it does not prevent falls,” she says. “In fact it may cause injury, and it may cause death.”

While there are circumstances where restraint may be appropriate McCabe says, “it is not there as a prolonged intervention”. Doing so, she says, “is an infringement of their human rights”.

After the 7.30program aired and one day before the Royal Commission hearings began, the federal government committed to stronger regulations around restraint, including that homes must document the alternatives they tried first.

Restraint by drugging

Another kind of restraint which has come into focus through the Royal Commission is chemical restraint. Psychotropic medication is currently prescribed to 80 percent of people with dementia in residential care – but it is only effective 10 percent of the time.

“We need to look at other interventions,” says McCabe. “The first to look at is: why is the person behaving in the way that they are? Why are they responding that way? It could be that they’re in pain. It could be something in the environment that is distressing them.”

She notes people with dementia often have “perceptual disturbances” – “things in the environment that look completely fine to us might not to someone living with dementia”. Wouldn’t you act out of character if your blue floor suddenly became a miniature sea, or a coat hanging on the door turned into the Babadook?

“It’s about people understanding of what it’s like to stand in the world of people living with dementia and simulate that experience for them,” says McCabe.

Whether through physical force or prescription, a dependence on restraint shows the extent to which dementia is misunderstood at the detriment of the autonomy and dignity of the sufferers. This misunderstanding is compounded by the fact that dementia is often present among other complex health problems.

Yet, and as the media may sensationally suggest, the aged care sector isn’t staffed by the callous or malicious. It is filled with good people, who are often overstretched, emotionally taxed and exhausted.

Dementia Australia is advocating for mandatory training on dementia for all people who work in aged care. This covers residential aged care, but could also extend to hospitals. Crucially, it encompasses community workers, too.

“Of the 447,000 Australians living with dementia, 70 percent live in the community and 30 percent live alone,” notes McCabe. “It’s harder to monitor community care, it’s less visible and less transparent. We have to make sure that the standards are across the board.”

It is only through listening to people living with dementia – recognising that while yes, they have a degenerative cognitive disease, they deserve to participate in the decision-making around their life and wellbeing – that our approach to it has evolved. Previously, people believed that it was dangerous to allow sufferers to cook, even to go out unaccompanied.

Likewise, it is crucial that we continue to afford people with dementia the full rights of personhood, however unfamiliar they may become. Only then can meaningful reform be made possible.

Besides, if for no other reason (and there are many other reasons), action is in our own selfish interest. The chances, after all, that you or someone you love will develop dementia are high.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

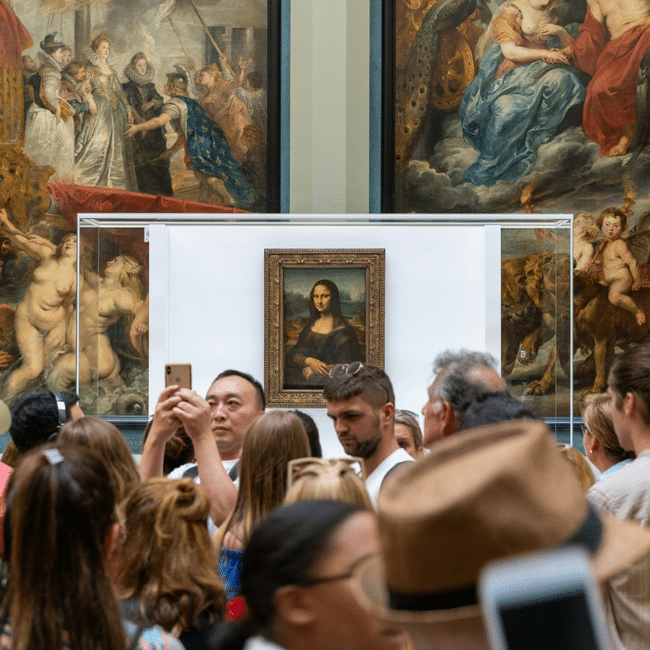

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP