Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Jack Hume The Ethics Centre 8 DEC 2016

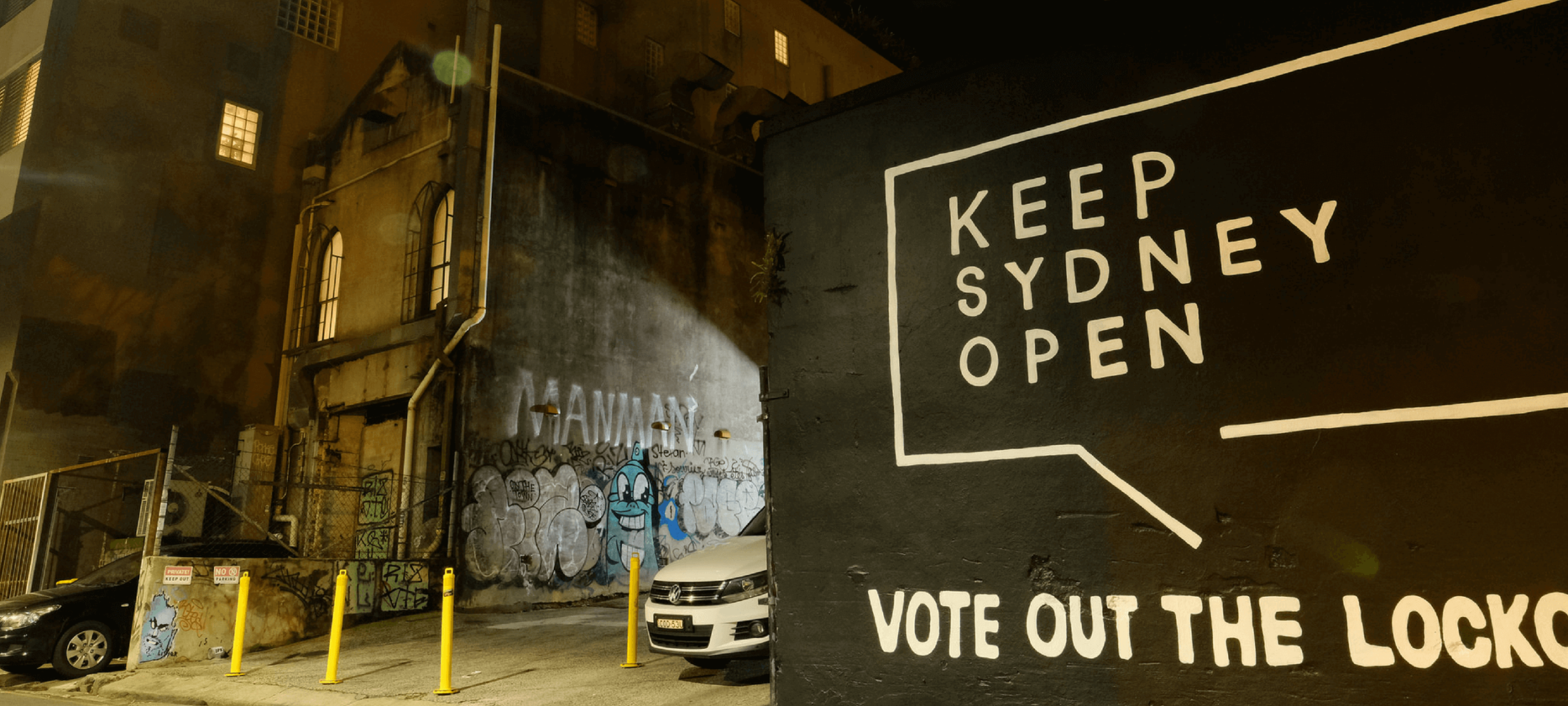

The New South Wales lockout laws were introduced in early 2014 in the wake of a great tragedy – the loss of human life to alcohol-fuelled violence.

Following the recommendations of an independent inquiry by Ian Callinan QC in 2016, the government decided to soften them. It shows that when we legislate in the wake of a tragedy, our judgement can be reactive. In the future, let’s measure our reactions against evidence.

When lockout laws were introduced in Sydney, alcohol related violence was on a downward trend. Even if people were afraid of becoming victims of violence, they were actually less likely to be attacked than in the past.

There is something to be learned from reflecting on the climate in which these laws were passed. We should be thinking about risks in terms of their likelihood, not in terms of how much we fear them. But that’s very hard, as we can see with another example – shark attacks.

People overestimate the likelihood of a shark attack in the same way they do other events they seriously fear, like terrorism and natural disasters. A study on Australian perception of sharks found that Sydneysiders believe shark attacks occur twice as often as they actually do, and fatal ones four times as often.

“Exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe they occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.”

This isn’t surprising. Research tells us we believe things are more likely to occur if we can easily call to mind examples of when they’ve occurred. And disturbing examples are easier to recall. The process of judging the probability of an event by how easy we find it to think of examples is known as the availability heuristic.

Emotional information is easier to remember, and so the availability heuristic has an interesting relationship with news coverage. Emotional news content prompts our attention, invariably placing demands on further coverage, which we will remember more easily.

News media is highly responsive to issues its audiences are interested in, and as a result those issues get more coverage. This pulls people into a feedback loop whereby their demands for further coverage lead them to believe events are more probable than they really are.

“Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line.”

For example, exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe crimes occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.

Knowing all this, we should expect people to overestimate the probability of events that provoke fear – violence, terrorism, plane crashes and natural disasters – particularly while they’re fresh in our memory. This effect is seen not just in how we speak and think about probability, but in how we act to protect ourselves, which brings us back to NSW policy.

Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line. Lockout laws are said to have been bad for Sydney’s culture and night-time economy. The public backlash forced the review that recommended loosening the reins of the lockout laws.

“Once news providers and their audience are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.”

The point is not whether lockout laws are effective in decreasing the threat of violence (which they have been in Sydney CBD), but the conditions through which they came about. These included media coverage on disturbing and unusual events – in particular, ‘one-punch’ killings – which caused fear and demanded attention, plus a campaign to increase awareness.

When the media reports on disturbing and unusual events at the same time that campaigns are run to increase awareness for them, the basic ingredients for a feedback between news media and its audiences are met. Once news providers and their audiences are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.

Shark nets are installed with the expectation of reducing the risk of shark attacks but they do this at the expense of marine life. They come as a response to the fact Australia has an above average incidence of shark attacks, which appear to be increasing. But let’s put this in perspective – the risk posed by sharks is still extremely low, accounting for two deaths in 2016 and one death in 2017.

The availability heuristic has unconscious components. Usually, people aren’t aware they’re estimating probability based on their fallible and selective memory. When people are unaware of how emotions, personal experiences and exposure to similar events can affect their judgements, they make unconsciously biased decisions.

Without appropriate consideration, people are at risk of basing important decisions on forces they aren’t consciously aware of. They may be led to support invasive or expensive regulations to protect themselves from risks that are highly unlikely. Where these regulations have undesirable side effects, like marine animal deaths, cultural damages to nightlife or the closure of businesses, this can mean real consequences for unreal problems.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The Ethics Alliance: Why now?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Consent

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership