Twitter made me do it!

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingScience + Technology

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 5 SEP 2016

In a recent panel discussion, academic and former journalist Emma Jane described what happened when she first included her email address at the end of her newspaper column in the late nineties.

Previously, she’d received ‘hate mail’ in the form of relatively polite and well-written letters but once her email address was public, there was a dramatic escalation in its frequency and severity. Jane coined the term ‘Rapeglish’ to describe the visceral rhetoric of threats, misogyny and sexual violence that characterises much of the online communication directed at women and girls.

Online misogyny and abuse has emerged as a major threat to the free and equal public participation of women in public debate – not just online, but in the media generally. Amanda Collinge, producer of the influential ABC panel show Q&A, revealed earlier this year that high profile women have declined to appear in the program due to “the well-founded fear that the online abuse and harassment they already suffer will increase”.

Twitter’s mechanics mean users have no control over who replies to their tweets and cannot remove abusive or defamatory responses.

Most explanations for online misogyny and prejudice tend to be cultural. We are told that the internet gives expression to or amplifies existing prejudice – showing us the way we always were. But this doesn’t explain why some online platforms have a greater problem with online abuse than others. If the internet were simply a mirror for the woes of society, we could expect to see similar levels of abuse across all online platforms.

The ‘honeypot for assholes’

This isn’t the case. Though it isn’t perfect, Facebook has a relatively low rate of online abuse compared to Twitter, which was recently described as a “honeypot for assholes”. One study found 88 percent of all discriminatory or hateful social media content originates on Twitter.

Twitter’s abuse problem illustrates how culture and technology are inextricably linked. In 2012, Tony Wang, then UK general manager of Twitter, described the organisation as “the free speech wing of the free speech party”. This reflects a libertarian commitment to uncensored information and rampant individualism, which has been a long-standing feature of computing and engineering culture – as revealed in the design and administration of Twitter.

Twitter’s mechanics mean users have no control over who replies to their tweets and cannot remove abusive or defamatory responses, which makes it an inherently combative medium. Users complaining of abuse have found that Twitter’s safety team does not view explicit threats of rape, death or blackmail as a violation of their terms of service.

The naïve notion that Twitter users should battle one another within a ‘marketplace of ideas’ . . . ignores the way sexism, racism and other forms of prejudice force diverse users to withdraw from the public sphere.

Twitter’s design and administration all reinforce the ‘if you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen’ machismo of Silicon Valley culture. Social media platforms were designed within a male dominated industry and replicate the assumptions and attitudes typical of men in the industry. Twitter provides users with few options to protect themselves from abuse and there are no effective bystander mechanisms to enable users to protect each other.

Over the years, the now banned Milo Yiannopoulos and now imprisoned ‘revenge porn king’ Hunter Moore have accumulated hundreds of thousands of admiring Twitter followers by orchestrating abuse and hate campaigns. The number of followers, likes and retweets can act like a scoreboard in the ‘game’ of abuse.

Suggesting Twitter should be a land of free speech where users should battle one another within a ‘marketplace of ideas’ might make sense to the white, male, heterosexual tech bro, but it ignores the way sexism, racism and other forms of prejudice force diverse users to withdraw from the public sphere.

Dealing with online abuse

Over the last few years, Twitter has acknowledged its problem with harassment and sought to implement a range of strategies. As Twitter CEO Dick Costolo stated to employees in a leaked internal memo, ‘We suck at dealing with abuse and trolls on the platform and we’ve sucked at it for years’. However, steps have been incremental at best and are yet to make any noticeable difference to users.

How do we challenge the most toxic aspects of internet culture when its norms and values are built into online platforms themselves?

Researchers and academics are calling for the enforcement of existing laws and the enactment of new laws in order to deter online abuse and sanction offenders. ‘Respectful relationships’ education programs are incorporating messages on online abuse in the hope of reducing and preventing it.

These necessary steps to combat sexism, racism and other forms of prejudice in offline society might struggle to reduce online abuse though. The internet is host to specific cultures and sub-cultured in which harassment is normal or even encouraged.

Libertarian machismo was entrenched online by the 1990s when the internet was dominated by young, white, tech-savvy men – some of whom disseminated an often deliberately vulgar and sexist communicative style that discouraged female participation. While social media has bought an influx of women and other users online it has not displaced these older, male-dominated subcultures.

The fact that harassment is so easy on social media is no coincidence. The various dot-com start-ups that produced social media have emerged out of computing cultures that have normalised online abuse for a long time. Indeed, it seems incitements to abuse have been technologically encoded into some platforms.

Designing a more equitable internet

So how do we challenge the most toxic aspects of internet culture when its norms and values are built into online platforms themselves? How can a fairer and more prosocial ethos be built into online infrastructure?

Changing the norms and values common online will require a cultural shift in computing industries and companies.

Earlier this year, software developer and commentator Randi Lee Harper drew up an influential list of design suggestions to ‘put out the Twitter trashfire’ and reduce the prevalence of abuse on the platform. Her list emphasises the need to give users greater control over their content and Twitter experience.

One solution might appear in the form of social media app Yik Yak – basically a local, anonymous version of Twitter but with a number of important built-in safety features. When users post content to Yik Yak, other users can ‘upvote’ or ‘downvote’ the content depending on how they feel about it. Comments that receive more than five ‘down’ votes are automatically deleted, enabling a swift bystander response to abusive content. Yik Yak also employs automatic filters and algorithms as a barrier against the posting of full names and other potentially inappropriate content.

Yik Yak’s platform design is underpinned by a social understanding of online communication. It recognises the potential for harm and attempts to foster healthy bystander practices and cultures. This is a far cry from the unfettered pursuit of individual free speech at all costs, which has allowed abuse and harassment to go unaddressed in the past.

It seems like it will require more than a behavioural shift from users. Changing the norms and values common online will require a cultural shift in computing industries and companies so the development of technology is underpinned by a more diverse and inclusive understanding of communication and users.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

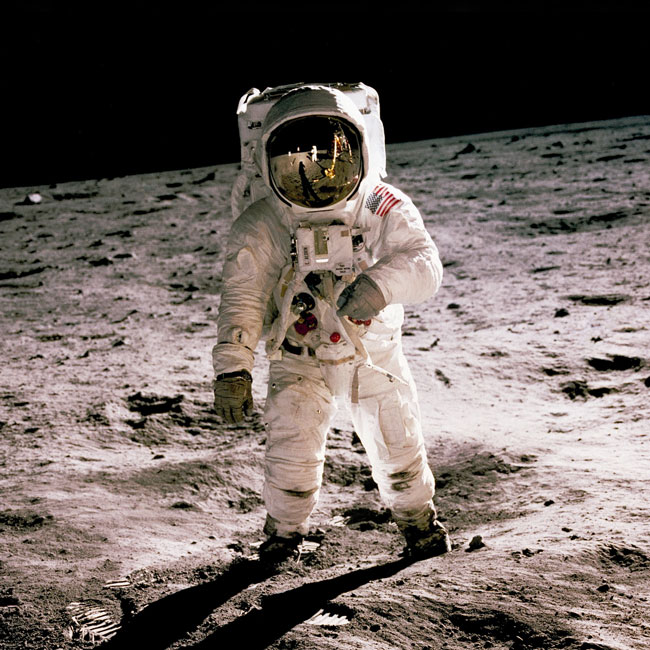

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture