What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Cris Parker 20 MAR 2019

“I am a trusted advisor.” That is how the man described himself when he approached me at the end of a conference.

We had gathered to discuss the implications of the Royal Commission into banking and finance and how that industry could emerge with a stronger ethical backbone.

“What is the best way to get that ethical message across?” asked the man in front of me.

Well, part of the problem was right there on his business card. You can’t self-nominate trust. You have to earn it. You can’t appropriate it yourself with a wishful job title or marketing slogan. You have to do the work and leave it to others to decide if you can be trusted. Or not.

A greater focus on trust itself

Trust has been seen as a top business priority and growing in importance over the past few years, especially after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 where people’s life savings were misused by the people in institutions that had promised to take care of them. The rise of the populist Occupy movement four years later was a warning shot to those in power that resonated globally.

However, much of the conversation since then about the poor reputation of business has failed to come to terms with the enormity of the task ahead. Trust is often spoken about as the currency that allows companies the privilege of taking care of another person’s wealth.

Not so much is said about the process of getting there – or even whether trust is the outcome companies should be focused on.

After all, having people’s trust does not necessarily mean that you are trustworthy.

Dealing in deception

Why should “trust” not be an end in itself? Well, US stockbroker and financial advisor Bernie Madoff was widely trusted by his wealthy investors before they realised they had been collectively fleeced of $US64.8 billion in the largest Ponzi scheme in history.

Closer to home in Australia, conman Hamish McLaren took $7.66 million from 15 separate victims – many of whom were referred to him by friends and family. McLaren was so trusted that one woman handed over her divorce settlement without even asking his last name.

McLaren is the subject of The Australian newspaper’s most recent podcast series “Who the Hell is Hamish?”.

Trust, by itself, is not always what it is cracked up to be.

Restoring confidence and trust

So the question is not “How can we get people to trust us again?”, but should be instead “What can we do to become trustworthy?”. Organisations need to focus on the process of getting there, rather than the result. It will take time, there needs to be consistency in behaviour and there’s an element of forgiveness that needs to be addressed.

Forgiveness means that the forgiver needs to believe that you won’t behave that way again. Declaring your best intentions doesn’t work, it needs to be seen.

Being trustworthy means that people in your organisation behave ethically because it’s the right thing to do, not because it will make people trust them again. A reputation for trustworthiness is, again, not something you can just anoint yourself with.

A solid reputation is bestowed upon you and comes through an accumulation of other people’s personal experiences of you and your work.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has provided the business world with a wealth of pithy and insightful quotes through his annual letters to shareholders.

One is said to be: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently”.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. An initiative of The Ethics Centre, The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

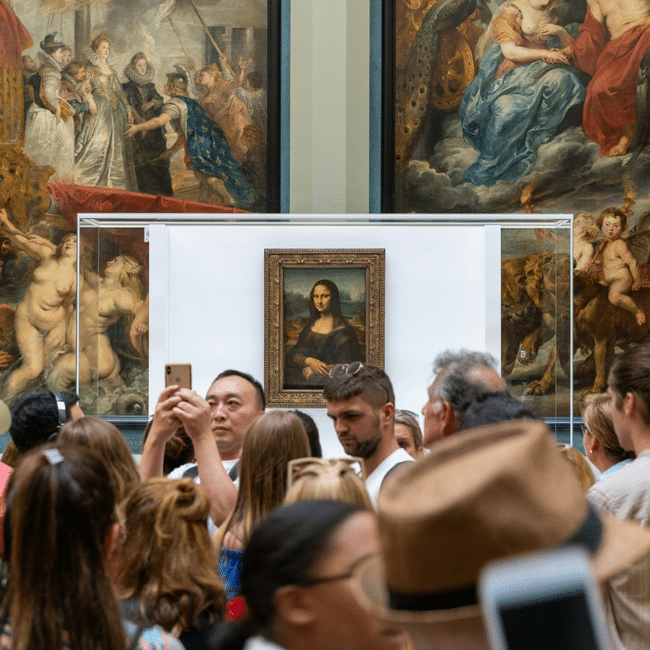

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP