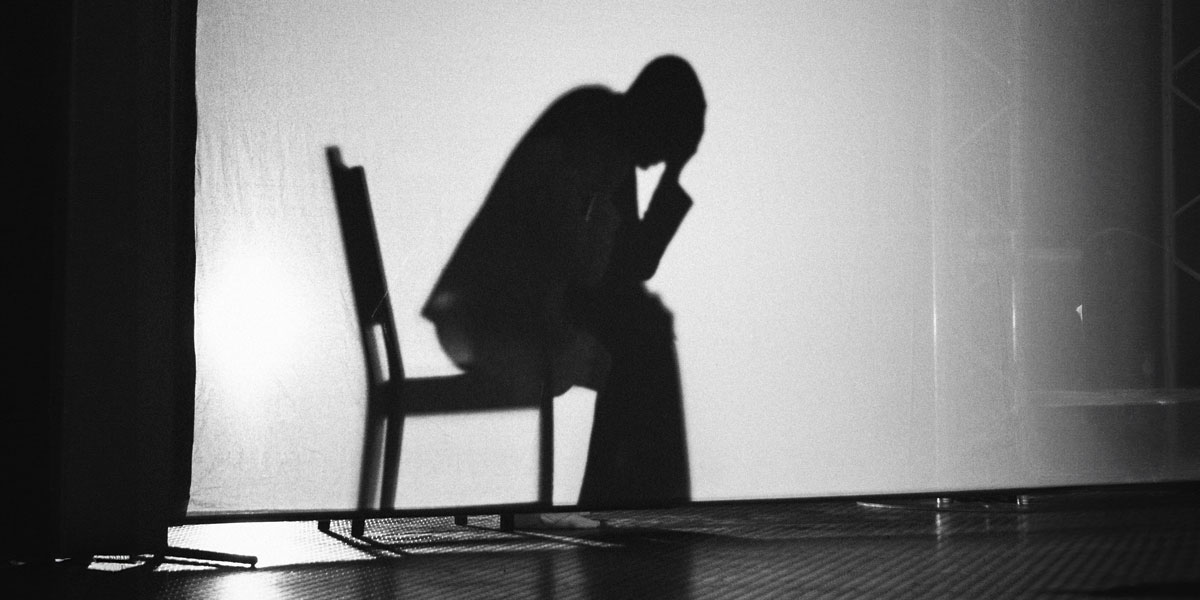

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 24 FEB 2025

In recent years, I have had an increasing number of conversations with people who feel overwhelmed by world events.

They describe the world as wracked by multiple crises of a magnitude such that efforts to reform or repair what is broken is simply futile. This attitude is not confined to those who are poor, oppressed or marginalised. This particular feeling seems to be divorced from personal circumstances – with even the privileged experiencing the same grim outlook.

Especially troubling is the fact that this feeling has been building, despite all of the evidence that Earth has become, on average, a safer, more peaceful place. A decreasing percentage of people live in abject poverty. Infant mortality rates are declining. There are fewer famines and more to eat. As a whole, the ‘four horsemen of the Apocalypse’ have been left playing cards in the stable.

Of course, specific individuals and groups still suffer the full panoply of ills that can afflict the human condition. But, overall, things have been getting better at the same time that people have come to believe that the world is a place of deepening doom and gloom.

One can easily think of an explanation for the divergence between reality and perception. First, is the power of individual stories. A compelling narrative of one person’s suffering can easily be taken as representative of the whole. It’s the same general phenomenon that leads us to feel better whenever we encounter a narrative in which the ‘underdog’ triumphs over the more powerful rival. These figures are swiftly ‘universalised’ to the point that any one of us can see our own possibilities reflected in that of the protagonist. So, when our stories tilt from the positive to the negative we are likely to see our view of the world take on a pessimistic hue.

This brings us to the second reason for this negative outlook. Unfortunately, the media (in all its forms) has ‘discovered’ that ‘bad news’ sells. Or to be more precise, bad news attracts and retains an audience in a way that positive news does not. The implications of this ‘insight’ have been grossly magnified by the emergence of social media – with its insatiable drive for eyes, ears, minds, etc. One of the most depressing stories I have heard, in recent years, is of a publisher that monitors every second of a story’s online life. The moment interest begins to flag, I am reliably advised, the instruction is to ‘bait the hook’ with something that implies ‘crisis’. So, what might properly be considered ‘troubling’ is elevated to the point where it feels like an existential threat posing a risk to all. Few remember the details when (almost inevitably) the more mundane truth emerges. What remains is the feeling – and facts rarely disturb established feelings.

These factors (and a host of others – too numerous to mention here) have combined to help generate a creeping sense that one might as well disengage and let the world go to hell in the proverbial ‘handbasket’. Let’s not bring children into a failing world. Let’s limit our attention to things within our span of control (not much). Let’s not vote – it’s pointless …

The deeply disturbing thing about all of this is that the temptation to withdraw because of the perceived futility of engagement gives rise to a self-fulfilling prophecy grounded in that great enemy of democracy; despair.

The truth of democracy (and markets for that matter) is that even the least powerful individual can change the world when working with others. Remarkably, we don’t even have to plan and coordinate for collective action to have a powerful effect. Indeed, one need not be ‘heroic’ (in the ‘Nelson Mandela’ sense) to be an author of momentous events. It’s just that you are unlikely ever to know when your decision or action tilted the world on its axis. Often it just requires a person to fall just a smidgen on the right side of a question. And when enough people do the same, there is progress.

Despair is the absence of hope that this is possible. It is a deceit that makes us fail – not because we never could succeed but because it destroys our belief in the possibility that we can be effective agents for change.

If we succumb to despair, then our possibilities collapse – not because we are powerless but because we believe ourselves to be.

Australia should aspire to be one of the world’s great democracies. It’s in our bones – dating back to South Australia that, in the late nineteenth century, brought into the world the first modern democracy in which all adults could not only vote but take up public office – irrespective of sex, gender, race or creed. For years, the secret ballot was known as the “Australian Ballot’. In 1900, Australia held more patents per head of population than any other country in the world. Yes, there were all the problems of colonisation, racism, sexism and a plethora of wrongs. And yes, we went backward for a while after Federation. But that reality did not give rise to despair.

Things actually can get better. Democracy is the vehicle for doing so; not because it demands so much of us as individuals – but because it demands so little. We just need to allow ourselves a small measure of hope to defeat despair. We need to take just a small, individual step forwards. Do this together, and nothing can stop us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Rawls

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology