Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 9 FEB 2023

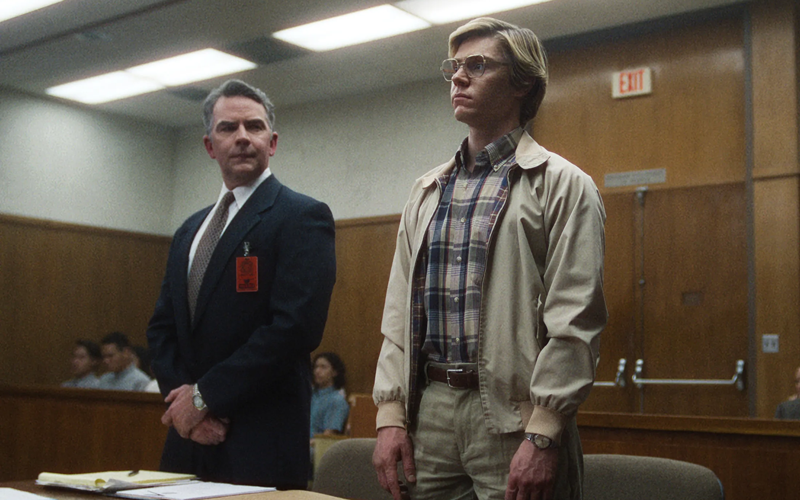

In January 2023, actor Evan Peters took to the stage to accept a Golden Globe for his performance as Jeffrey Dahmer in the surprise streaming success Monster – The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

It was a moment of odd contrast. There was Peters, dressed in a Dior suit, surrounded by opulence of the highest order and luxuriating in the most comfort and security imaginable — rich, safe, protected — accepting an award for his portrayal of a serial killer. More than that, the families of Dahmer’s victims were nowhere to be seen. As the actor collected the gong, those whose lives had been forever shaped by the crimes of a serial killer — second-order victims, whose narratives had been used for art — were off-screen.

It was a moment that crystalised the strangeness of our modern obsession with true crime, an obsession that is taking over the entertainment industry, and swamping podcast feeds and our small screens. In swathes of the Western World, we are safer than ever before from the threat of another Dahmer — and yet, in our post-Making A Murderer world, ripped from the headlines stories of violence and immorality are everywhere, even as such experiences are becoming, for most of us, as alien as stories set on Mars.

And such stories have real-life victims who are still with us; still alive, and in many cases, still grieving. These people who deserve emotional security are being ignored and overwritten by Hollywood.

Why then can’t we get enough of Ed Gein, and Ted Bundy, and the mountain of murderers that fill up our screens? What are the ethics of engaging with these traumas casually, over dinner, or on our way to work? And what can we do to make this immensely popular sub-genre genuinely ethical?

Why Are We Getting Off On Murder?

It would be wrong to suggest that our current moment of true crime consumption is a total deviation from past trends. Stories of horror and amoral behaviour have been with us since at even earlier than the time of the Brothers Grimm — most oral storytelling revolved around bloodshed, deviants, and murder.

It would also be wrong to suggest that true crime is an empty or useless art form. Art is therapeutic because it allows us to explore and imagine heinous violence and immorality from the safety of our homes. It’s a tool for processing collective fear; collective horror. It’s a way for us to explore how we feel about our own moral systems, by examining the lives and actions of those who deviate from those systems.

However, it’s the “based on a true story” tag that makes true crime distinct. It is hard to imagine that Monster would have the same impact on the mass culture if it was a total fiction. The “true” in “true crime” is part of the sell.

Engaging in the world of true crime means engaging in a world where serial killers lurk around every corner. For those of us living in cities in the Western World, that is far from true. Serial killers were always the aberration to the rule. Now, they’re positively alien — in the U.S., serial crime makes up less than one percent of all crimes recorded. For those of us with class privilege, our deaths will come, most likely, from heart disease, not a sociopath in oversized glasses who will later mummify our heads.

Why true crime has blossomed in the context of these cultural shifts is hard to say. Could it be a result of the passivity baked into entertainment these days? So much of us binge shows to tune off, switch out, and relax on the couch. True crime is excitingly different. Podcasts like My Favourite Murder, or smash hits like Making A Murderer gives audiences an opportunity for further engagement that extends after the credits roll. You can read Wikipedia pages. You can listen to more podcasts; watch spin offs; read testimonies. And that means you can become a sort of detective of your own, sniffing out leads, becoming not just a watcher, but a researcher.

Blood On Whose Hands?

The cultural context for our obsession with true crime adds a string of ethical dilemmas to consuming it. For a start, our obsession is coming a time where we are more able than ever to educate ourselves on the crooked and fundamentally broken nature of the police force. Most true crime is ‘copaganda’, saturating the populace with the myth that most police officers are inventive, savvy artists stringing together clues, rather than overfunded, inadequate mental health professionals at best, and the violent arm of the state at worst.

True crime also plays uncomfortably into pre-existing racial divides. In most true crime shows produced in the United States, Australia and the UK, the victims come from ethnic backgrounds that are not white. The cops, by contrast, are white. The looming threat of the white savior narrative is thus unavoidable. Just as problematically, race is an unspoken presence in most true crime, rarely acknowledged, and glossed over by artists in favour of the flashier, gorier elements of these stories.

Finally, real-life crime means real-life victims. Dahmer’s victims have children; friends. These crimes leave intergenerational traces – there is a legacy of pain that drips down bloodlines after a life is cruelly and inhumanely snuffed out. Not only have these second-order victims lost a loved one, they’ve seen that loved one turned into newspaper headlines and bit players in a swathe of miniseries and podcasts.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families. The reason for this responsibility is two-fold. Firstly, these stories would, devastatingly, not have happened were it not for the victims. In the worst, most painful way, Dahmer was who he was because of the people he killed. His story is their story, and any Hollywood creative who tells that story and makes a dime is profiting off the pain of victims. Ryan Murphy, Monster’s creator, has a net worth of $150 million. Evan Peters has a net worth of $4 million. Both have enjoyed significant financial success from Monster that the second-order victims of Dahmer have not.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families… The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment.

The pain of those whose lives were affected by Dahmer provides the second reason for the responsibility of true crime artists — these victims and their families are just that. Victims. The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment. All the award shows that Peters and Murphy get to swan about at seem actively exploitative, given the human suffering that they took from real-life, and fashioned for the screen.

The way to resolve this responsibility is proper financial remuneration. These families deserve to be compensated for their stories, and for their pain. Moreover, such an obligation extends beyond just those involved with Monster, and implicate all true art creators, no matter the medium. How often have you listened to a true crime podcast, in which a grisly murder is being detailed, only to have your experience interrupted by a jocular advert for mattresses and at-home meal kits? These moments sit the grisly murder next to the adverts that make the creators of such content wealthy – throwing into focus that the true crime industry is just that — an industry.

Sure, in a capitalist system, all art has to be commercially minded to some extent – art is expensive to make, and artists deserve to be compensated. But the integration of advertising into true crime feels particularly craven. The money must be shared. Those who deserve to be paid should be paid.

None of this is an argument for shutting down true crime art, or censoring it or banning it in any way. True crime, for its flaws, serves a purpose. It can make us think about class; about context; about law. But to be truly ethical, true crime must shift its relation to the victims who are involved in these stories. Otherwise, there’s blood on the hands of more than just the murderers.

For more insights into our consumption of true crime, tune into the FODI22 discussion, The Crime Paradox

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships