Where do ethics and politics meet?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 26 APR 2019

In the Western philosophical tradition, ethics and politics were frequently deemed to be two sides of a single coin.

Aristotle’s Ethics sought to answer the question of what is a good life for an individual person. His Politics considered what is a good life for a community (a polis). So, for the Ancient Greeks, at least, the good life existed on an unbroken continuum ranging from the personal through the familial to the social.

In some senses, this reflected an older belief that individuals exist as part of society. Indeed, in many cultures – in the Ancient world and today – the idea of an isolated individual makes little sense. Yet, there are a few key moments in Western philosophy when we see the individual emerging.

St Thomas Aquinas argued that no individual or institution has ‘sovereignty’ over the well-informed conscience of the individual.

René Descartes placed the self-certain subject at the centre of all knowledge and in doing so undermined the authority of institutions that based their claims to superiority on revelation, tradition or hierarchy. Reason was to take centre stage.

Aquinas and Descartes, along with many others, helped set the foundation for a modern form of politics in which the conscientious judgement of the individual takes precedence over that of the community.

Today, we observe a global political landscape in which ethics can be hard to detect. It’s easy to say that many politicians are ruled by naked greed, fear, opinion polls, blind ideology or a lust for power.

This probably isn’t fair to the many politicians who apply themselves to their responsibilities with care and diligence.

In the end, ethics is about living an examined life – something that should apply whether the choices to be made are those of an individual, a group or a whole society.

MOST POPULAR

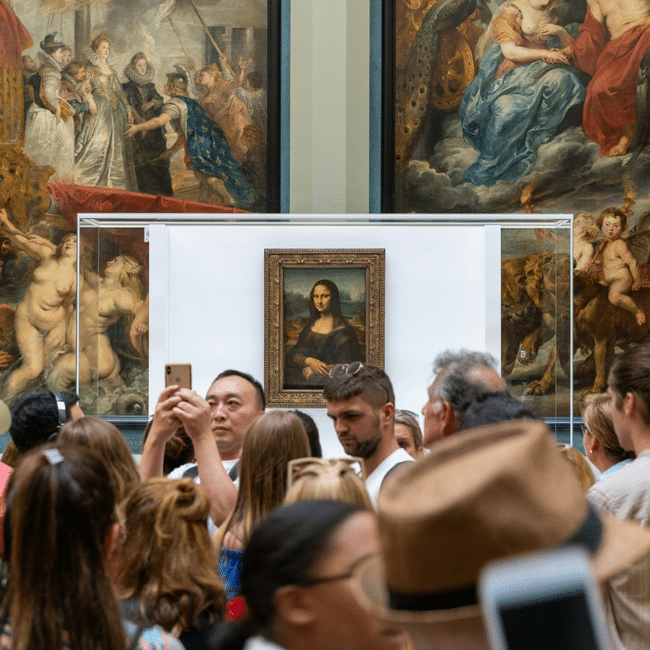

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP