Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Naomi Barnes 22 JUL 2025

This is a story about moral panic: a familiar social pattern where fear swells, villains are cast, and quick solutions race ahead of careful thought. Like any good tale, it begins with a wolf.

Charles Perrault (1628-1703), grandfather of the modern fairy tale, knew that morality could be controlled through stories – such as those later adapted by the Brothers Grimm – like Little Red Riding Hood, where characters like The Wolf are easily understood as folk devils.

But morality plays, where the terrible actions of evil people teach us to be good, aren’t just a staple of fantasy: they are also a key feature of media storytelling. The British sociologist, Stanley Cohen, argued that the media creates moral panics by creating ‘folk devils’, which incite panic in the community. In a way, the media is saying the Big Bad Wolf is real.

We saw this in the 1980s, when the media fuelled the “Satanic Panic” that surrounded the tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons & Dragons, amplifying claims that it led to self-harm and Satanism. In this story, the children who played the game were folk devils, coordinating to corrupt their peers.

Many times, a moral panic is an exaggeration of a social challenge that does exist. It’s often based on real events, but the story is blown out of proportion, especially compared to other, more serious, problems. When something becomes a moral panic, we’re inspired to act fast, often without careful consideration or scrutiny of the narrative we’re fed. Its moral nature can more easily justify a harsh response because the stakes feel so high. This can lead to hasty or bad decisions, which can end up doing far more harm than good.

It’s important that we can identify the signs of a moral panic, so we can respond appropriately. Using a diagnosis tool with embedded ethical questions, like the steps below, can help us think critically about what we are being told. We can think about which bits might be exaggerated or amplified, and whether the solutions offered will actually address the core issue.

Prevention becomes prejudice

The first stage in the creation of a moral panic is the identification of a folk devil. Cohen noted that there are several clusters of who, or what, gets branded as a folk devil, with it often resting on pre-existing prejudices or stereotypes. Common candidates are young people, working class or violent men. Sometimes it’s new media, like rock music, social media or video games. Other times it’s groups that are often the targets of discrimination, such as single mothers, welfare cheats, refugees or asylum seekers.

One of the risks of a moral panic is that it becomes a mask for prejudice. Not all wolves devour grandmothers, just as not all young men are violent, or all childcare workers are predators. Although real danger can exist, moral panic begins when appearance, identity or difference becomes mistaken as a threat.

It is the leap from concern to caricature that makes a folk devil.

Once we know the villain, we construct the story. A challenge to the social order becomes a moral panic because of the way it’s communicated. When the media goes beyond describing something and injects morally judgemental language, using words like “thug” or “bludger” or “monster”, it is more likely to trigger an emotional response.

How the media and community tell the story also determines not just who the suitable enemy is, but who the suitable victim might be. The victim will be someone the public can easily identify, such as children or innocent girls and women, but typically someone everyone knows.

This next stage is crucial to how moral panic is sustained. This is where the media calls on public experts to comment. Religious leaders are often drawn in to help sustain concern about a social challenge as they are already framed as guardians of morality. Sometimes it’s academics or activists or the representative of a non-government organisation who is called upon to argue over the nuances of the case, lending it greater credibility.

Hasty solutions

A moral panic demands solutions. But, just as there is no rescuing Little Red without an axe, solutions can be extreme while temperatures run high. The very urgency of a moral panic can inspire us to look to options we might normally reject due to their high cost or because of the compromises involved. A moral panic might lead to blanket bans, a reduction in civil liberties or even calls for the death penalty.

This leads to the last step in a moral panic, when policymakers get involved. When the media, backyard barbeques, school pick up and letters to MPs are all begging the government to intervene, it’s more likely for the government to do so, lest it look weak or, worse still, complicit in the moral failing. But good policy can take years to develop, but a moral panic demands it is made fast, as seen with the Australian government’s youth social media ban. Sometimes that produces more problems while failing to solve the deeper underlying issues that contributed to the moral panic. Banning Dungeons & Dragons wouldn’t have solved the underlying mental health issues that triggered the panic in the first place.

The Big Bad Wolf never really left the storybooks, we just keep giving him new names, faces and new reasons to panic. There really are wolves out there, and we need to find ways to deal with them. But when temperatures run high, we risk offering fairy tale solutions to real-world problems.

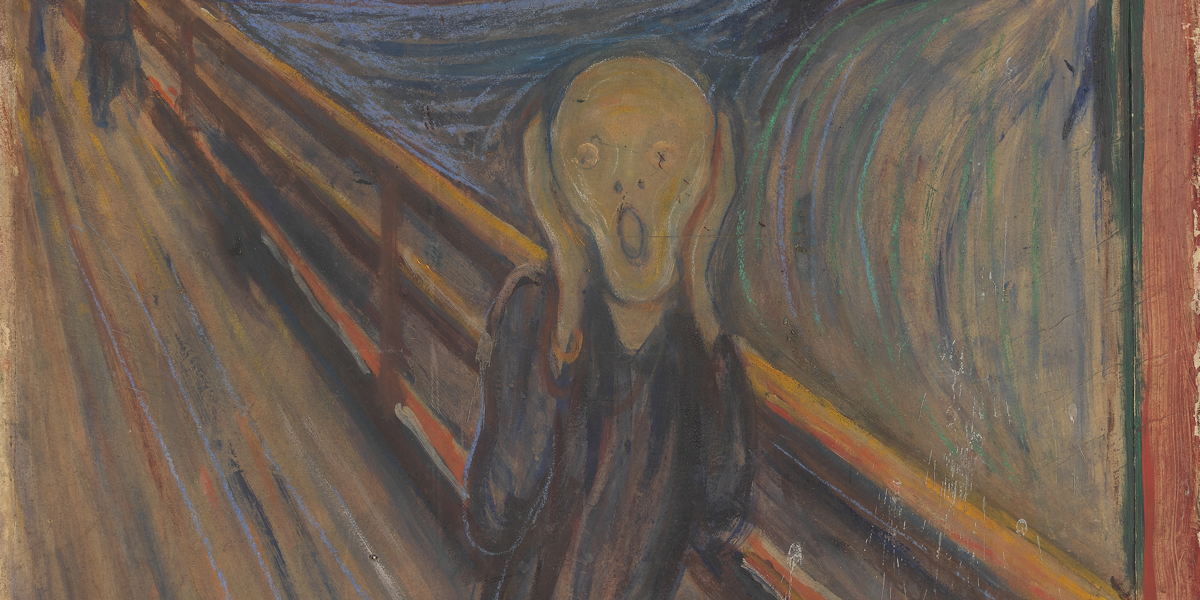

Image: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

BY Naomi Barnes

Associate Professor Naomi Barnes is a researcher at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) interested in how political actors perform and respond to crises. With a specific focus on moral panics and manufactured crises, she focuses on education politics in Australia, the US and the UK. Naomi is editor in chief of a forthcoming International Handbook of Schooling in Times of Crisis. Naomi is regularly asked to comment on how Australian teachers should respond to perceived threats to Australian nationalism, identity, and democracy. Naomi is the co-course co-ordinator of a future-focused Humanities and Social Sciences Curriculum Project at QUT and lectures future teachers in Modern History and Civics and Citizenship.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture