Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 APR 2024

Any country wishing to advance or defend its strategic interests has recourse to two types of power: hard and soft.

Richard Marles’ release of the government’s most recent Defence Strategic Review, coming as it does just before Anzac Day, provides an opportunity to examine how well Australia is positioned in relation to the oft-neglected “defensive” aspect of soft power.

Any potential adversary knows that a low-risk way to wound a diverse, multicultural society is to pick it apart until it turns against itself. They are right. Look at the cracks that have opened up at home under the strain of a distant war between the state of Israel and Hamas. It has led to a massive rise in antisemitism and a resurgence in Islamophobia.

Indeed, the first thought of many was that the murderous rampage at Bondi Junction was a terrorist attack connected to conflict in the Middle East. Two days later, a surge of communal violence was unleashed in response to the wounding of two clerics in a terrorist incident.

Thanks to good management by police, politicians and community leaders, our worst fears were not realised. However, we should be warned. Malicious actors will have been encouraged by evidence of how easy it would be to ignite the tinder of a larger conflagration. They will be readying themselves to stoke the embers with their weapons of choice: misinformation and disinformation. How can we defend against this?

There are two aspects of soft power in its defensive form that we must deploy now to build resilience for the future. First, we must work to restore trust in our private and public institutions. Second, we need to harness the power of unifying narratives.

The first of these tasks is essential if we are to protect ourselves against the corrosive effects of misinformation and disinformation. Our current approach mostly relies on regulation and surveillance to control the worst of it.

However, a liberal democracy with a commitment to free speech will always fight with the equivalent of one hand tied behind its back. So, we need to work twice as hard; investing in the development of individuals and institutions who can be trusted to offer sound guidance at times when it really matters.

Trustworthiness needs constant effort

When natural disasters strike, we all tend to look to the ABC for critical information – even those who are concerned about the national broadcaster and its editorial stance. Trust in our public institutions should not be the exception. It needs to become the norm. This will happen only if those institutions are consistently trustworthy.

Becoming trustworthy is an acquired skill. It needs constant effort. Trustworthiness is not something that can be produced by anti-corruption commissions, by regulation or surveillance. It requires investment in a positive commitment to ethics.

As a public, we need to know that our leaders merit our trust at times when it really matters. No matter what those dedicated to sowing the seeds of dissension might tell us, no matter what conspiracy theories might be abroad, we need good reason to believe that when it comes to the crunch, our leaders have the knowledge, skills and character to be relied on. In short, we need to invest in the nation’s “ethical infrastructure”.

Second, we need to make far more of our “secular myths”. Like all such stories, their power resides in something larger than the immediate facts. They speak to something deeper – which brings me to Anzac Day. Many nations ground their identity in stories of triumph, whether it be the defeat of an armed foe or the overthrow of an illegitimate or oppressive regime. Anzac Day offers something different.

Those of us who celebrate Anzac Day not only remember the fallen. We also find meaning in a striking example of “noble failure”.

To try your best. To venture all, even if you fail. To maintain honour, even to the end. These are ideals to which anyone can aspire – even if, in reality, we so often fall short.

This ideal is not bound by religion, culture, language or heritage. About 70 First Nations people fought at Gallipoli. The Turks, who won the engagement, still honour what took place – despite the horrors of war. People of all faiths and none have found moments of inspiration in a story that does not glorify war – only the spirit of those “warriors” who try to be and to do their best, even when they fail.

Of course, this is just one narrative. How many others are out there waiting to be deployed for the common good?

We spend billions of dollars on the implements of hard power. But on Anzac Day we should remember its complement – the soft power of a shared ethos that underpins a cohesive society and safety at home.

This article was originally published in The Australian Financial Review.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

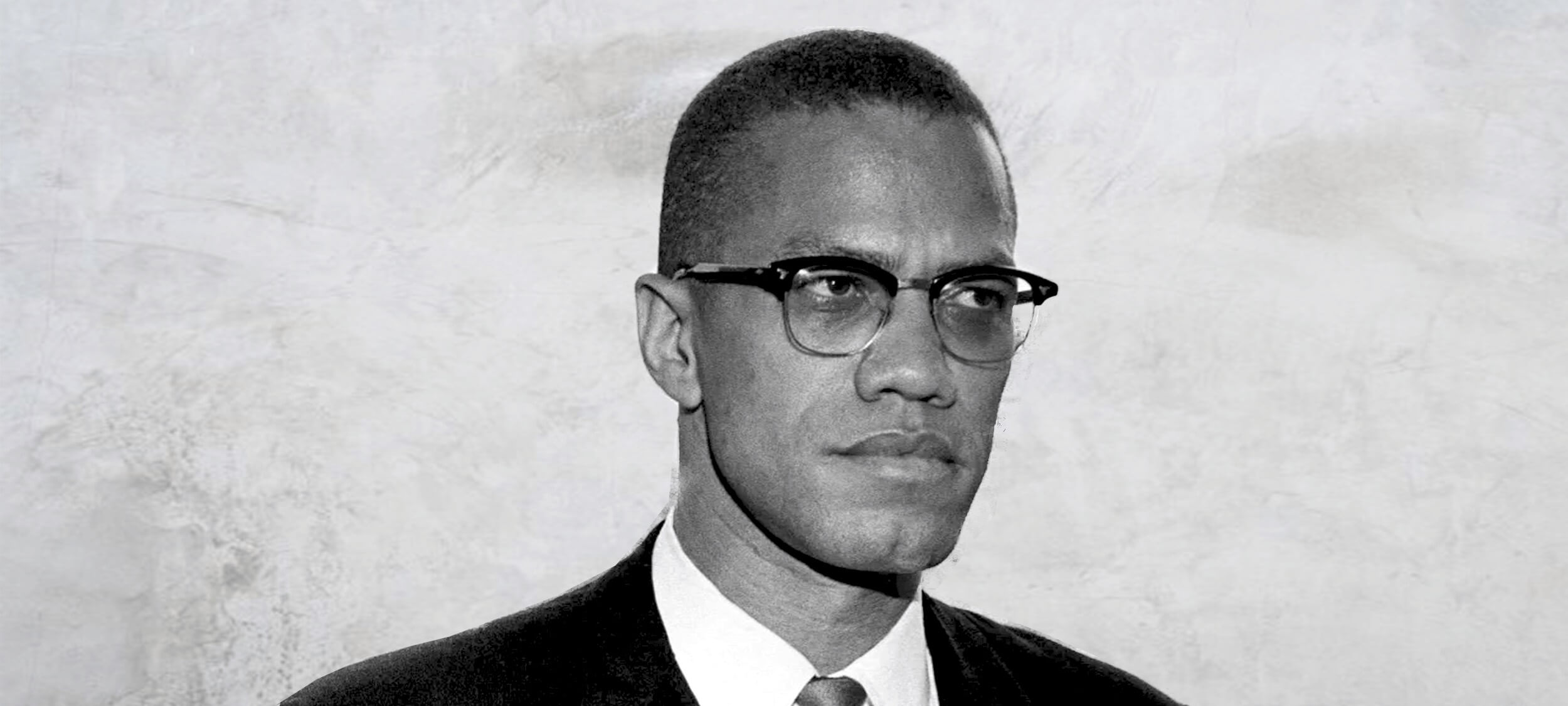

Big Thinker: Malcolm X

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Education is more than an employment outcome

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights