You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Steve Vanderheiden The Ethics Centre 30 SEP 2015

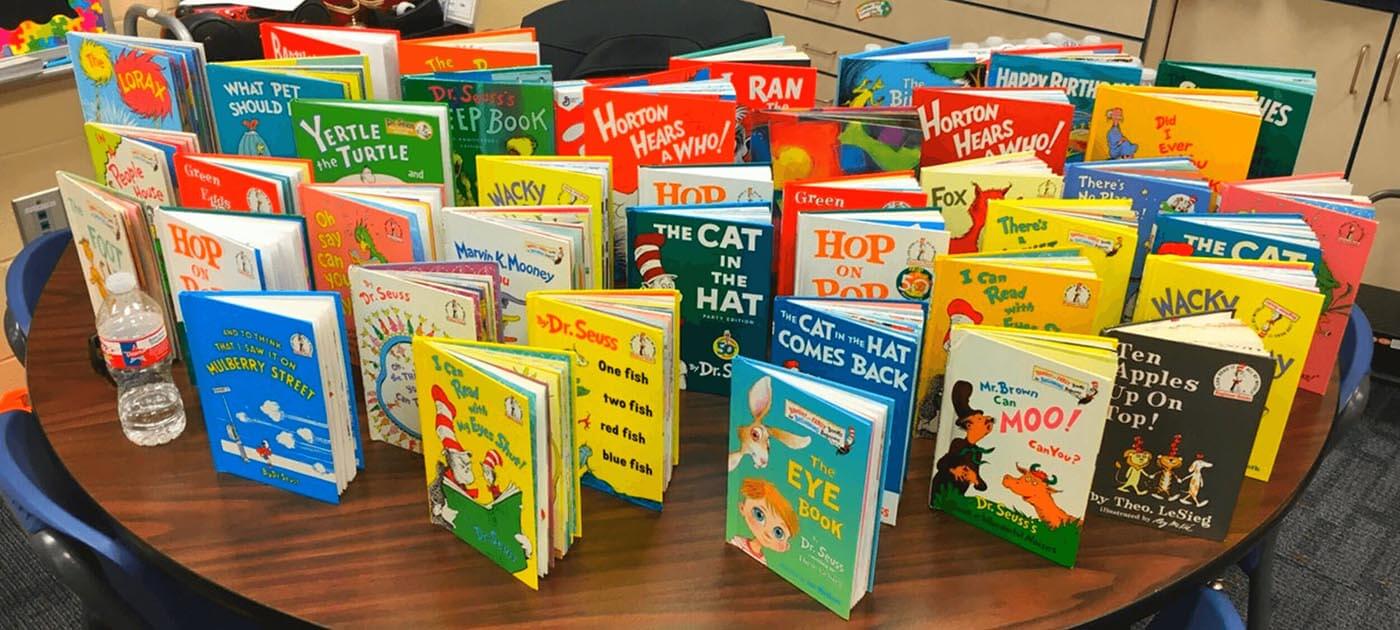

Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax explores the consequences of deforestation and the environmental costs of development. It concludes with the Once-ler, the narrator of the story who is principally responsible for deforestation of the decimated Truffula tree, entrusting its final seed to a young boy. He implores the child, “Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack. Then the Lorax and all of his friends might come back.”

The Once-ler, wracked by guilt for his complicity in this environmental disaster, passes along responsibility for reversing damage done by his generation to a child. The Lorax suggests the young take on duties of planetary stewardship where adults have failed.

Is this fair? Perhaps the generation responsible for mucking up the planet has lost its moral authority to try and save it. So the task of conservation is inherited by those with a longer-term stake in its future.

That adults might vest hope for a better planet in our children is both edifying and deeply troubling. Edifying because the environmental record of the world’s children bests that of adults by default. The young have not yet begun to reproduce the patterns of behavior that implicate their parents – resource depletion, biodiversity loss, climate change…

Troubling because they may reproduce them in future. We cannot realistically expect young people socialised into a world of willful environmental neglect to behave much differently than their parents have. Adults cannot so easily absolve themselves of the responsibility of addressing environmental harm they have caused.

Rather than saving the planet, a more modest objective might be to refrain from making it much worse for our children. Even this is a daunting prospect. Patterns of energy use dependent on fossil fuels all but guarantee that global temperatures will continue to rise. For most, climate change is no longer a debate about “if” but “how severe?”

We may still hope to make the planet better for our children in other ways. For instance, by adding to the richness of human culture and the stock of beneficial technologies. When it comes to climate though, a more appropriate aim might be to refrain from chopping that last Truffula tree. To preserve our remaining forests so our children might be able to see the proverbial Brown Bar-ba-loots, Swomee-Swans or Humming Fish in their native habitats rather than natural history museums.

Doing this will be challenging. It will require an often uncomfortable reflection on what drives global environmental degradation. In Seuss’ tale the insatiable demand for thneeds – the ultimate commodity – drives the Truffula deforestation. This implicates our heedless consumerism in the causal chain of degradation alongside the Once-ler.

When we consume things we don’t need, and when the industry around these commodities is obviously unsustainable despite our obliviousness to this fact, we contribute to resource depletion. What’s more, we add to the attitudes and norms that suggest this is a private matter, answerable only to private consumer preferences and not larger public concerns for equity or sustainability.

Worst of all, we teach our children to do the same.

The first step in reducing our negative impact upon the planet must be to understand how and where we make the impact we do. We need to understand alternatives that yield comparable value to us with a lighter toll upon the planet. Consuming more conscientiously will leave our children a better planet and make them better citizens of it. Though it requires us to consume differently and less.

Thinking about the long-term consequences of our choices will also help. We cannot plausibly claim to value our children’s future while discounting the future value of current investments in sustainable infrastructure or future costs of unsustainable current practices.

To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

Our deeds announce our concern for the welfare of future generations more accurately than our words or thoughts. Thinking about such choices must be accompanied by some changes in course. Citizens must demand better public choices be made rather than acquiescing to worse ones as unavoidable products of political inertia or inviolable market forces.

The tendency to shift problems across borders is no less insidious than passing them to our children or grandchildren. To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

As role models for our children our success in stopping environmental harm will matter less than our sincerity in the efforts we make. If we honestly try to maintain the planet, our example will help make them into the kind of people our planet needs.

For as the Once-ler interprets the Lorax’s cryptic final word, “UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships