Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 1 OCT 2012

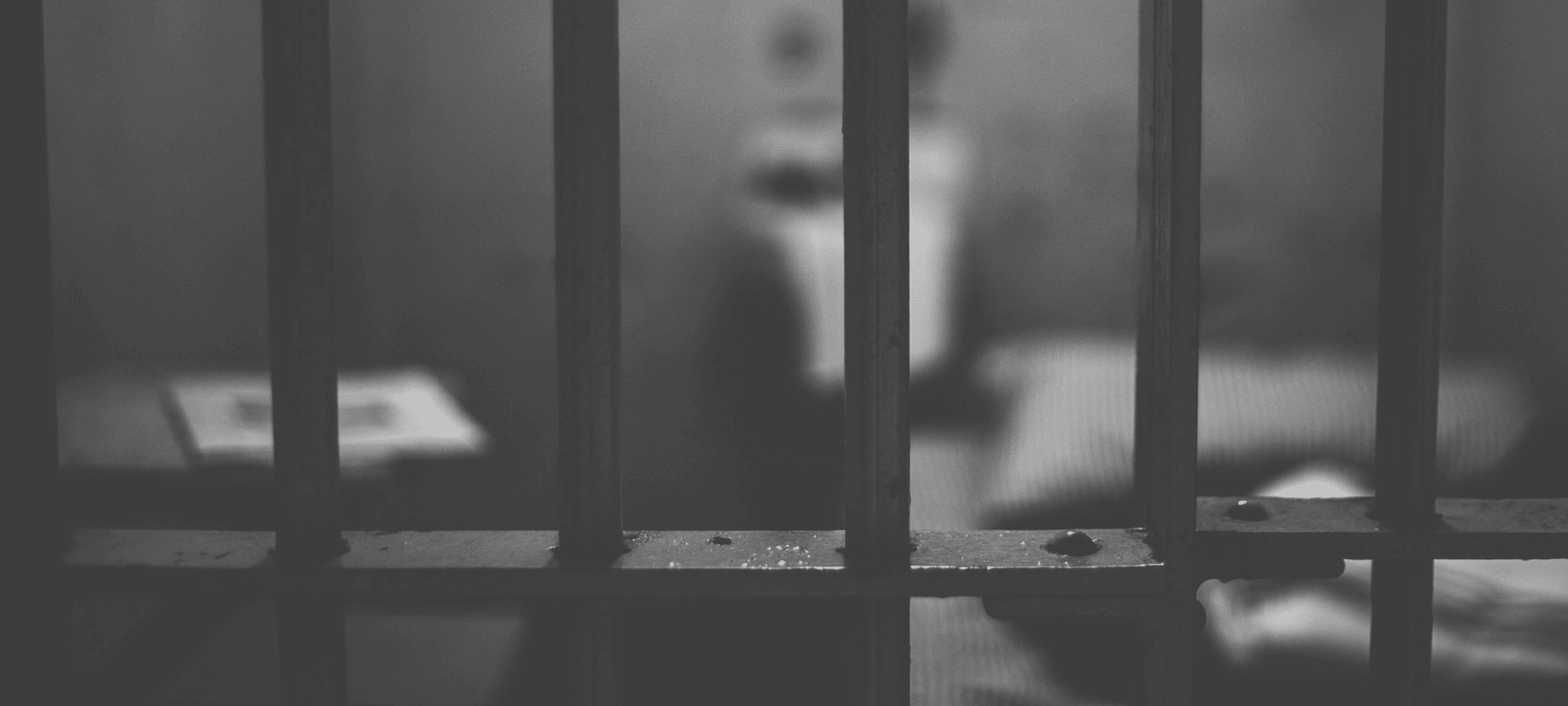

The institutional abuse of children detained by the government of the Northern Territory is a bone-chilling example of what occurs when raw power is exercised without ethical restraint.

The scenes broadcast by the ABC’s Four Corners program in July 2016 were the stuff of nightmares – the kind of thing done by ‘other people’, in ‘other countries’, in ‘other circumstances’. But this nightmare became real, for us – here and now. The prime minister announced a Royal Commission to investigate what had happened and why.

But first, we need to look at the general conditions that made the unthinkable possible. Those conditions do not just apply in the context of juvenile ‘justice’ in the Northern Territory. Australian governments are responsible for the detention of people throughout our states and territories as well as on Manus Island and Nauru. In every case, there is a risk (and often a reality) of people with power exercising it in a manner that fails the test of the most basic standards of decency.

Every person who is detained deserves to be treated with a basic measure of respect – even those who committed the foulest crimes still retain their intrinsic dignity as a ‘person’.

Second, we need to reckon with arguments that the ‘ends justify the means’ and the prisoner or detainee is the author of their own fate – that they ‘deserve what they get’.

Normally, you would expect parliaments in a liberal democracy to place strict curbs on the exercise of power by government officials. But in recent years, the tendency has been to take the opposite path – to smooth the way for excess.

This has been done by creating numerous exceptions to the application of usual legal and ethical restraints that have been designed, over millennia, to tame power – such as judicial oversight, civil and criminal liability, media scrutiny and respect for individual rights like habeas corpus.

Australia has wide exemptions – for members of the intelligence services, for those detaining suspected terrorists, for detention centres and, as evidenced in the Four Corners report, for those guarding juvenile detainees in the Northern Territory.

Section 215 of the Northern Territory’s Youth Justice Act confers a wide-ranging immunity on virtually all people working with juvenile detainees. Specifically it says:

“The person is not civilly or criminally liable for an act done or omitted to be done by the person in good faith in the exercise or purported exercise of a power, or the performance or purported performance of a function, under this Act.”

It is yet to be determined whether or not the behaviour revealed by Four Corners was done ‘in good faith’. If so, then the people responsible can never be held to account. The parliament of the Northern Territory has, for all intents and purposes, written a blank cheque.

Cultural failure is the responsibility of those in positions of authority. It cannot be addressed by lopping off the heads of a few ‘rotten apples’ buried in the depths of the barrel.

These provisions were likely enacted as part of a law-and-order campaign. It probably never occurred to legislators that children might be tear-gassed, bound to chairs (and all the rest) by their guards. I’ve no doubt they are now appalled at what has been done. But their lack of forethought does not lessen their responsibility for what they have made possible. It only deepens it.

Governments bear the ultimate responsibility for the treatment of those they detain. Such responsibilities cannot be outsourced. Every person who is detained deserves to be treated with a basic measure of respect – even those who committed the foulest crimes still retain their intrinsic dignity as a person. If we do not deny this for the worst of humanity, how can it be absent for children? They may be angry. They may be rebellious. They may be violent. Even so, they are children. Our children.

It is almost certainly the case that those responsible for abuse are not monsters. They will be just like most of us – most likely unable to conceive of treating their own children as they have those in detention. It’s an age-old puzzle. How can basically good people end up doing such terrible deeds?

It will be revealing to see if we take a wider look at what made this national disgrace possible and ask where else the same seeds have been planted.

There are a number of factors that were likely at work here:

- The guards could have been conditioned to look at their task through a purely legal lens – ‘if it’s not illegal it’s not wrong’.

- An element of tribalism – people conforming to the norms of a tight (usually isolated) group that overwhelms the dictates of individual conscience.

- A belief they were serving a ‘higher good’ (law and order) and their child victims deserved harsh treatment.

- A belief that the methods employed were ‘best practice’ sanctioned by a ‘respected authority’.

- A sense the children were not deserving of basic respect because they were ‘not like us’ – most likely linked to their Aboriginality.

- And most importantly, people within the group may have questioned what was being done while lacking the moral courage to speak out for fear (usually well-founded) of retribution.

Cultural failure is the responsibility of those in positions of authority. It cannot be addressed by lopping off the heads of a few ‘rotten apples’ buried in the depths of the barrel. Instead, we need to look at the ‘rotten barrel’ – and who made and maintained it.

How we respond to this issue will tell us a lot about Australia and its people. In particular, it will be revealing to see if we take a wider look at what made this national disgrace possible and ask where else the same seeds have been planted.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Settler rage and our inherited national guilt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z’s future

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The value of principle over prescription

The value of principle over prescription

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 1 OCT 2012

As a child, I visited the ski fields of New South Wales but once. So, you would think that my most enduring memory of that vacation would be of snow. But it is not. Rather, I remember a lamb chop—or, more particularly, the circumstances giving rise to a BBQ in a bushland clearing somewhere out of Cooma.

The chop had been purchased from a local butcher who sold his fare from an old-fashioned shop. The butcher operated from within an area enclosed by fly screen and served his customers through a sliding hatch. Inside, activity centred on a large wooden block set on a floor strewn with sawdust producing the earthy scent of freshly sawn timber. Having purchased our chops, we drove on into the country where we found a picnic spot somewhere off the road. In a family ritual, we older children were sent off to gather twigs for kindling and sticks for a fire used to cook our chops on a grill set on rocks surrounding the small fire. Having eaten, we made safe the fire and returned the area to how we had found it before ascending to the snow line.

Sadly, the experiences I describe have been almost regulated out of existence. Butchers can no longer dress their floors with sawdust. Travellers may no longer set small fires to cook their lunch in bushland settings but must find a ‘permanently constructed fireplace at a site surrounded by ground that is cleared of all combustible materials for a distance of at least two metres all around’. The rules preventing such things have been introduced for perfectly good reasons: to promote safe eating and to prevent bushfires. But was it really necessary to impose such uniform rules (e.g. hard surfaces for all butchers)? Or might we have done better to specify some general principles (e.g. around health and safety) and leave butchers and travellers to make responsible decisions about how best to meet their obligations?

There was a time when Australians were more willing to accept risk in return for a larger measure of freedom.

I should clarify two likely points of contention. First, I am not opposed to rules and regulations per se. Comprehensive and consistent regulation makes good sense in some areas of life (aviation standards come to mind). Second, I am not merely pining for a lost golden age of my youth. Life (and society) moves on. Rather, my concern is a deeper one—that Australia and Australians are becoming an overly compliant people and that our archetypal self (the knockabout and resourceful larrikin questioning of authority) now exists only in our rhetoric.

I recently discussed this issue with former Liberal minister, Amanda Vanstone. For the sake of lively conversation, she proposed a radical pruning of the regulatory thicket with all regulation being suspended unless proven to be both necessary and effective. Most proposals for reform are cautious and incremental, aiming only to remove the dead wood. The Vanstone proposal was to replace the whole tree. But what might be planted in its place?

I proposed three general principles that, in my opinion, do the work of most regulations:

- That no person may intentionally or recklessly cause harm to another

- That no person may expose another to harm without their free, prior, and informed consent

- That no person may engage in unconscionable conduct to the detriment of another.

Although Ms Vanstone inclines towards the lawyer’s typical suspicion of broad principle (perhaps concerned about the relative lack of certainty and the attendant scope for judicial activism), she agrees that principles like these would fill the vacuum caused by a serious reduction in regulatory burden.

But then it occurred to us that our entire conversation might have been based on a false assumption: that Australians actually want less regulation. But what if they don’t?

I still recall Peter Costello’s comment, when Federal Treasurer, that business leaders would often demand of him—in one breath—less regulation and more certainty about where ‘the line is drawn’. He could meet one of their demands, but not both. So, what did these leaders really want? They wanted certainty, which led them to prefer regulation. And the wider community? Would it have a greater appetite for the exercise of personal judgement and responsibility? Would it opt for principle over prescription? These are the central questions.

There was a time when Australians were more willing to accept risk in return for a larger measure of freedom. No doubt there were mishaps, but perhaps not as many as some would fear. For the most part, the sawdust on the floor of butchers’ shops was regularly replaced when soiled, and the diligent merchant produced an environment no less hygienic than found amongst the hard surfaces mandated by today’s regulators. Bush fires are a scourge but few are the product of camp fires left unattended or carelessly set. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, natural causes (such as lightning strikes) are the most prevalent. And to the extent that humans cause fires, the real menace lies in the acts of arsonists rather than the accidents of errant campers.

The proposal to do away with the majority of regulation may be unrealistic. However, the guiding sentiment is well-founded. Our world is largely populated by decent people. They are capable of developing a variety of innovative solutions to day-to-day challenges. Life loses some of its magic when creativity is constrained by a one-size-fits-all approach to managing risk.

Would it really be so bad if we were to trust ourselves and each other a little more?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

360° reviews days are numbered

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership