Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Karen Wyld 24 JAN 2019

Like clockwork, every January Australians question when is, or even if there is, an appropriate time to celebrate the nationhood of Australia.

Each year, a growing number of Australians acknowledge that the 26thof January is not an appropriate date for an inclusive celebration.

There are no sound reasons why the date shouldn’t be changed but there are plenty of reasons why the nation needs to change.

I’ve written about that date before, its origins and forgotten stories and recent almost-comical attempts to protect a public holiday. I choose not to repeat myself, because the date will change.

For many, the jingoism behind Australia Day is representative of a settler colonialism state that should not be preserved. A nation that is not, and has never been fair, free or young. So, I choose to put my energy into changing the nation. And I am not alone.

People are catching up and contributing their voices to the call to change the nation, but this is not a new discussion. On 26 January 1938, on the 150thanniversary of the British invasion of this continent, a group of Aboriginal people in NSW wrote a letter of protest, calling it a Day of Mourning. They asked the government to consider what that day meant to them, the First Peoples, and called for equality and justice.

Since 1938, the 26thof January continues to be commemorated as a Day of Mourning. The date is also known as Survival Day or Invasion Day to many. Whatever people choose to call that day, it is not a date suitable for rejoicing.

It was inconsiderate to have changed the date in 1994 to the 26th January. And, now the insensitivity is well known, it’s selfish not to change the date again. The only reasons I can fathom for opposition to changing the date is white privilege, or perhaps even racism.

These antiquated worldviews of white superiority will continue to haunt Australia until a critical mass has self reflected on power and privilege and whiteness, and acknowledges past and present injustices. I believe we’re almost there – which explains the frantic push back.

A belief in white righteousness quietened the voices of reason and fairness when the first fleet landed on the shores of this continent. And it enabled colonisers and settlers to participate in and/or witness without objection decades of massacres, land and resource theft, rape, cultural genocide and other acts of violence towards First Peoples.

The voice of whiteness is also found in present arguments, like when the violence of settlement is justified by what the British introduced. It is white superiority to insist science, language, religion, law and social structures of an invading force are benevolent gifts.

First Peoples already had functioning, sophisticated social structures, law, spiritual beliefs, science and technology. Combining eons of their own advances in science with long standing trade relations with Muslim neighbours, First Peoples were already on an enviable trajectory.

Tales of white benevolence, whether real or imagined, will not obliterate stories of what was stolen or lost. Social structures implanted by the new arrivals were not beneficial for First Peoples, who were barred from economic participation and denied genuine access to education, health and justice until approximately the 1970s.

Due to systemic racism, power and privilege, and social determinants, these introduced systems of justice, education and health still have entrenched access and equity barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Changing the nation involves settler colonialists being more aware of the history of invasion and brutal settlement, as well as the continuing impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It involves an active commitment to reform, which includes paying the rent.

The frontier wars did not result in victory for settler colonialists, because the fight is not over. The sovereignty of approximately 600 distinctly different cultural/language groups was never ceded. Despite generations of violence and interference from settler colonialists, First Peoples have not been defeated.

“You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force. You have almost exterminated our people, but there are enough of us remaining to expose the humbug of your claim, as white Australians, to be a civilised, progressive, kindly and humane nation.”

‘Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights!: A Statement of the Case for the Aborigines Progressive Associations’, The Publicist, 1938, p.3

Having lived on this continent for close to 80,000 years and surviving the violence of colonisation and ongoing injustices of non-Indigenous settlement, the voices of First Peoples cannot be dismissed. The fight for rights is not over.

The date will change. And, although it will take longer, the nation will change. There are enough still standing to lead this change – so all Australians can finally access the freedoms, equality and justice that Australia so proudly espouses.

Karen Wyld is an author, living by the coast in South Australia

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

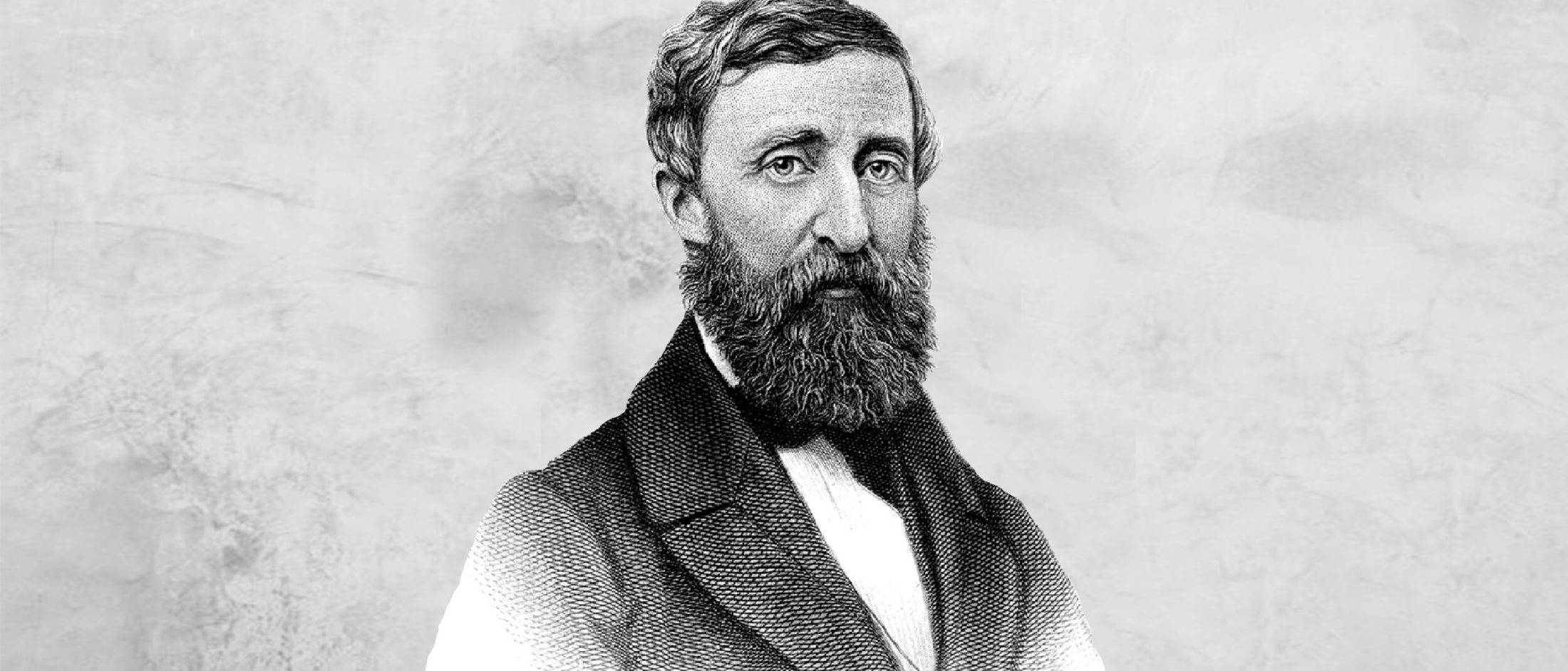

Big Thinker: Henry Thoreau

A tax evader, rebel philosopher and the grandfather of environmentalism, Henry Thoreau (1817—1862) practiced a back-to-nature experience of the natural world while opposing authority.

Though enjoying no great acclaim in his lifetime, today the name Henry David Thoreau resonates across philosophy, literature, political history, natural history and environmental science. His spirit of non-conformity, his rugged individualism and his ‘essentialist’ approach to living, have seen him mythologised as an American hero – and an ancestor of various ‘return to nature’ movements, too.

The son of a pencil maker, Thoreau was born in 1817 in Massachusetts, US. He demonstrated free minded dissent for institutions early in life. While at Harvard, he allegedly refused to pay for his diploma certificate. In his subsequent role as teacher, he rejected a recommendation for corporal punishment – by thrashing a random group of students to make a point, then resigning. Later, he would refuse to pay six years’ taxes. He saw it as surrendering his money to fund slavery and the government’s war in Mexico, both of which he vigorously opposed. For this, he was thrown in jail.

Civil Disobedience

Thoreau’s spirit of resistance coalesced in the libertarian manifesto Civil Disobedience. Unjust governments have no right bending citizens to their arbitrary laws and corrupt systems, he argued in the book. A free, enlightened state was only possible once that state “recognised the individual as a higher and independent power”, and enabled them to be “men first, and subject after”.

Rather than meekly obey, Thoreau said he was obliged “to do at any time what I think right” – even if that meant breaking the law. This idea of self-governance by individual conscience would later inspire Gandhi, Martin Luther King and others who took a principled stance against unjust rule.

It has also been widely critiqued. Violent and bigoted acts can, after all, easily be committed under the banner of self-righteousness. And what if two people divided on a matter by ideology or faith can’t settle their differences?

Lines in Civil Disobedience like, “That government is best which governs not at all” also make some question whether Thoreau’s libertarian politics tended towards anarchism.

Simple living, transcendentalism and the Walden experiment

A fellow resident of his home town, Ralph Waldo Emerson was a pivotal influence on Thoreau. He introduced Thoreau to transcendentalism – a movement which reacted against religious and intellectual trends, and enjoined each individual to forge their own “original relation to the universe”. Thoreau became a key figure in the movement. For him, solitude, simplicity, awareness and harmonious engagement with the wild were concrete ways to forge this relation. His philosophy as well as his science, insisted upon embodied understanding, rather than just a contemplative or discursive one.

In a forest cabin lent to him by Emerson, Thoreau conducted an experiment in simple living which would last two years and two months. His methods and reflections during this time became the classic work Walden – named after a pond which abutted the property. In it, with poetic eloquence, didacticism and free wheeling style, he lays out his view of a resigned, frivolous and wretched humanity, and how one is to instead rise above and “live deliberately”.

To achieve an existence which is pure and meaningful, Thoreau argued a life must be cultivated free from illusion and excess. He practiced a style of subsistence living through radical self-denial. Only essential needs were identified and met. A plausible misanthrope, he forswore conversation, sensuality, coffee, meat and alcohol, advising just one meal a day. To relinquish to the slightest temptation was to open the gates to moral disrepair. He even eschewed a doormat, “preferring to wipe my feet on the sod before my door.”

According to the American author John Updike, “Waldenhas become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible”.

Kathryn Schulz reads Thoreau’s hermitage as rather a renunciation of responsibility, and categorises it as “original cabin porn”.

“Being forever on the alert”

Shorn of distractions, purged of indulgences, Thoreau believed a greater awareness of the universe can bloom. But more vital to his philosophy was an “ethics of perception” – requiring rigorous attentiveness to the outside world as it was uniquely registered on the senses. This could be observing a sunset’s reflection on glass, or the miniaturised battle of ants. Through this expanded and intensified focus, man was empowered to elevate his life, in “infinite expectation of the dawn”.

A surveyor by trade, Thoreau said we must consciously endeavour to practice “the discipline of looking […] at what is to be seen”.He was suspicious of orthodox forms of knowledge and believed the “essential facts of life” come to us through “the perpetual instilling and drenching of the reality that surrounds us”. Truth, then, was deeply individualised communion between self and world, and the product of intuition and revelation, rather than logic or reason.

Natural as intrinsically valuable

Thoreau’s ideas around nature’s intrinsic value have had significant bearing on modern conservationism. The sublime beauty and order that could be perceived in natural phenomena were not, he thought, qualities projected onto it by humans. They were immanent. What’s more, “Whatever we have perceived to be in the slightest degree beautiful is of infinitely more value to us than what we have only as yet discovered to be useful and to serve our purpose”.

In other words, nature cannot be commodified. Priceless, it must be viewed on its own terms, rather than as a resource to serve human agendas and needs. His view was diametrically opposed to the anthropocentricism that characterised the industrial revolution’s frenzied assault upon lands and oceans, which would culminate in the raft of ecological crises facing us today.

Thoreau also drew attention to the hidden benefits and invisible services of plant and animal species. In one example, he considered the squirrel. To the average American, they were a pest. But if we recognised squirrels in a broader ecosystem context, we could honour them as “planters of forests”, noble little workers whose free labour humans couldn’t do without.

Thoreau recognised, too, that our ignorance of these hidden benefits makes us careless. Trampling over nature’s bounty, upending its fragile balance, we are liable to do untold damage – for which we may ourselves pay a dear cost. In this sense, he was prescient.

“I should be glad if all the meadows on the earth were left in a wild state,” he wrote, “if that were the consequence of men’s beginning to redeem themselves.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 24 JAN 2019

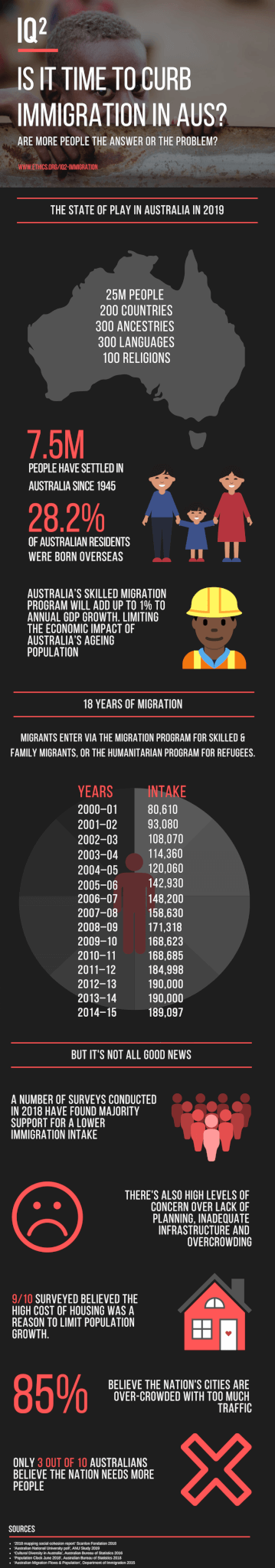

To curb or not to curb immigration? It’s one of the more polarising questions Australia grapples with amid anxieties over a growing population and its impact on the infrastructure of cities.

Over the past decade, Australia’s population has grown by 2.5 million people. Just last year, it increased by almost 400,000, and the majority – about 61 percent net growth – were immigrants.

Different studies reveal vastly different attitudes.

While Australians have become progressively more concerned about a growing population, they still see the benefits of immigration, according to two different surveys.

Times are changing

In a new survey recently conducted by the Australian National University, only 30 percent of Australians – compared to 45 percent in 2010 – are in favour of population growth.

The 15 percent drop over the past decade is credited to concerns about congested and overcrowded cities, and an expensive and out-of-reach housing market.

Nearly 90 percent believed population growth should be parked because of the high price of housing, and 85 percent believed cities were far too congested and overcrowded. Pressure on the natural environment was also a concern.

But a Scanlon Foundation survey has revealed that despite alarm over population growth, the majority of Australians still appreciate the benefits of immigration.

In support of immigration

In the Mapping Social Cohesion survey from 2018, 80 percent believed “immigrants are generally good for Australia’s economy”.

Similarly, 82 percent of Australians saw immigration as beneficial to “bringing new ideas and cultures”.

The Centre for Independent Studies’ own polling has shown Australians who responded supported curbing immigration, at least until “key infrastructure has caught up”.

In polling by the Lowy Institute last year, 54 percent of respondents had anti-immigration sentiments. The result reflected a 14 percent rise compared to the previous year.

Respondents believed the “total number of migrants coming to Australia each year” was too high, and there were concerns over how immigration could be affecting Australia’s national identity.

While 54 percent believed “Australia’s openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation”, trailing behind at 41 percent, Australians said “if [the nation is] too open to people from all over the world, we risk losing our identity as a nation”.

Next steps?

The question that remains is what will Australia do about it?

The Coalition government under Scott Morrison recently proposed to cap immigration to 190,000 immigrants per year. Whether such a proposition is the right course of action, and will placate anxieties over population growth, remains to be seen.

Join us

We’ll be debating IQ2: Immigration on March 26th at Sydney Town Hall, for the full line-up and ticket info click here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

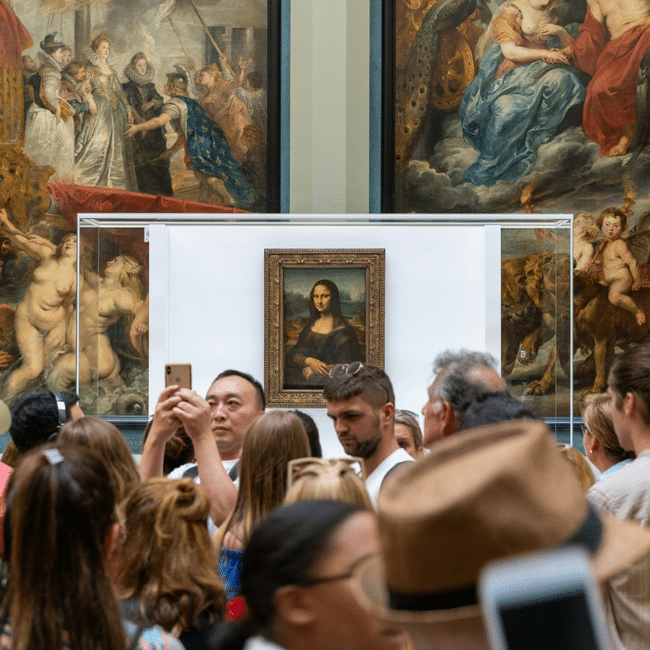

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the philosophical study of art. If you think about what is enjoyable, or valuable about artworks, and why art is important, then you are considering issues to do with aesthetics.

The study of aesthetics is tricky because there are so many different kinds of artworks and it is difficult to think about what they have in common or how they should be categorised or judged. A seminal question in the field of aesthetics is ‘what is art?’ – how ought art be defined? And this question alone has various answers depending on which theory is being applied.

Art defined.

Art includes sculpture, painting, plays, films, novels, dance and music. And it isn’t always clear what the category of art excludes – in large part because artists are always pushing boundaries. The creative nature of art sees works or objects being considered as ‘Art’ that provoke shock, outrage, censorship or exclamations of ‘That’s not Art!’.

Just think about the first time Marcel Duchamp tried to display an artwork called ‘Fountain’ in 1917. The urinal, a ‘found object’ was signed by the artist ‘R. Mutt, 1917’, and caused a riot of disagreement as to whether art must be created or made with one’s own hands or whether it can be intentionally chosen and displayed.

Is it the creation or the reception of the artwork that matters the most?

Who decides whether something is a work of art? Is it ‘the artworld’ of experts and critics? Is it the artist? Or is it the viewer? Many viewers may not understand what they are seeing or may not truly appreciate the skill involved in creating a particular artwork.

For instance, the first time one looks at a Rothko painting, which may appear as a blank canvas painted with a couple of coloured squares, a viewer may think, ‘I could have painted that!’ It is only with an understanding of Rothko’s technique that one may start to appreciate the effort he put in to create it.

And even if we appreciate the skill and effort an artist exerts, we may or may not feel any particular ‘aesthetic experience’ when looking at a piece of abstract or contemporary art, while watching an opera, or while reading a novel by Dostoevsky.

An individual perspective

One’s experience of art is subjective as individual tastes differ. And yet, if we are to claim that some artworks are better than others, or explain why some artworks stand the test of time and are valued by generations, we need to refer to some standards by which to judge them. Are there any features artworks must have to be considered as art? Should artworks be beautiful? Do they need to be moral? And who decides whether or not they meet this criteria?

Despite the historical interference by political and religious leaders who worry about the influence art may have in a society, debates as to what constitutes good art, aesthetically and even morally, has been a matter for debate for aestheticians.

Sometimes it takes time for something to be considered art, let alone to be considered aesthetically valuable. Think about Banksy’s graffiti art. It has been the case that unsuspecting council workers have removed graffiti from the side of a building only to later discover they have inadvertently eliminated a valuable artwork. And yet, not all graffiti is considered art or deemed valuable.

In fact, the opposite is true!

What makes Banksy an exception?

View this post on Instagram. "The urge to destroy is also a creative urge" – Picasso

A post shared by Banksy (@banksy) on

Definitions of art have changed over time. Traditional views of art usually cited ‘beauty’ as an important feature of artworks, but that has since altered. Indeed, is one meant to find the displayed urinal ‘beautiful’? An artwork need not be beautiful to be skilfully executed, meaningful and valuable.

The value of art in society

The defenders of art and its unique role in society usually claim art should be valued for its own sake. Aesthetic value is not to be valued instrumentally, for its financial value or for its status, or even for what we can learn from it or because it is deemed morally ‘good’. It may do any and/or all of these things, or none! Art is valuable because it affords an aesthetic experience.

In its creation and reception, as a form of self expression, imaginative engagement, cognitive as well as affective experience, source of individual and social reflection and contemplation, art has always been central to human life. If it is true that the arts capture and express something unique, and aesthetic experience is intrinsically valuable, then we should consider the place for the arts in society and support and value artists for the important contribution they make.

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is a senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP