What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Cris Parker 20 MAR 2019

“I am a trusted advisor.” That is how the man described himself when he approached me at the end of a conference.

We had gathered to discuss the implications of the Royal Commission into banking and finance and how that industry could emerge with a stronger ethical backbone.

“What is the best way to get that ethical message across?” asked the man in front of me.

Well, part of the problem was right there on his business card. You can’t self-nominate trust. You have to earn it. You can’t appropriate it yourself with a wishful job title or marketing slogan. You have to do the work and leave it to others to decide if you can be trusted. Or not.

A greater focus on trust itself

Trust has been seen as a top business priority and growing in importance over the past few years, especially after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 where people’s life savings were misused by the people in institutions that had promised to take care of them. The rise of the populist Occupy movement four years later was a warning shot to those in power that resonated globally.

However, much of the conversation since then about the poor reputation of business has failed to come to terms with the enormity of the task ahead. Trust is often spoken about as the currency that allows companies the privilege of taking care of another person’s wealth.

Not so much is said about the process of getting there – or even whether trust is the outcome companies should be focused on.

After all, having people’s trust does not necessarily mean that you are trustworthy.

Dealing in deception

Why should “trust” not be an end in itself? Well, US stockbroker and financial advisor Bernie Madoff was widely trusted by his wealthy investors before they realised they had been collectively fleeced of $US64.8 billion in the largest Ponzi scheme in history.

Closer to home in Australia, conman Hamish McLaren took $7.66 million from 15 separate victims – many of whom were referred to him by friends and family. McLaren was so trusted that one woman handed over her divorce settlement without even asking his last name.

McLaren is the subject of The Australian newspaper’s most recent podcast series “Who the Hell is Hamish?”.

Trust, by itself, is not always what it is cracked up to be.

Restoring confidence and trust

So the question is not “How can we get people to trust us again?”, but should be instead “What can we do to become trustworthy?”. Organisations need to focus on the process of getting there, rather than the result. It will take time, there needs to be consistency in behaviour and there’s an element of forgiveness that needs to be addressed.

Forgiveness means that the forgiver needs to believe that you won’t behave that way again. Declaring your best intentions doesn’t work, it needs to be seen.

Being trustworthy means that people in your organisation behave ethically because it’s the right thing to do, not because it will make people trust them again. A reputation for trustworthiness is, again, not something you can just anoint yourself with.

A solid reputation is bestowed upon you and comes through an accumulation of other people’s personal experiences of you and your work.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has provided the business world with a wealth of pithy and insightful quotes through his annual letters to shareholders.

One is said to be: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently”.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. An initiative of The Ethics Centre, The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleSOCIETY + CULTURE

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

ArticleBeing Human

The problem with Australian identity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath.

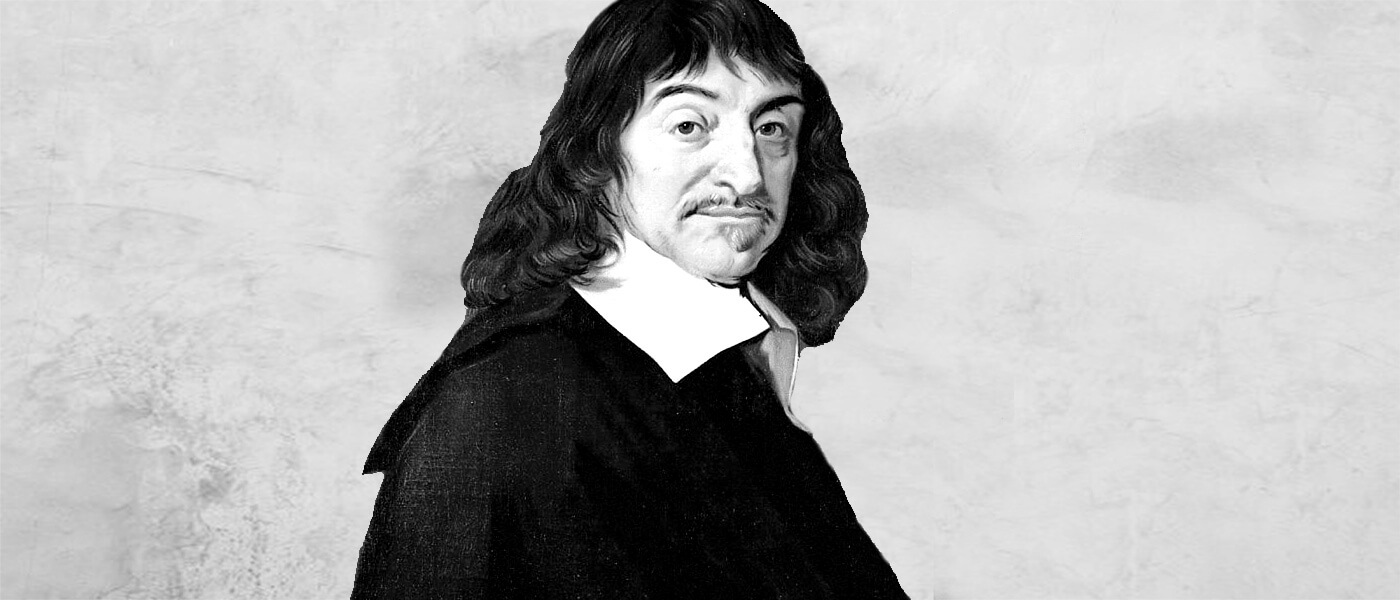

Big Thinker: René Descartes

René Descartes (1596—1650) is famous for the phrase, “I think, therefore I am”. He was a Frenchman writing in the early 17th century and was preoccupied with the question: What can we know for certain?

Descartes details a method of doubt in his key text Meditations on First Philosophy, published in 1641. It becomes crucial for rationalists that seek infallible knowledge. Rationalists rest their epistemological claims on pure reason, without recourse to the senses or experience (unlike the empiricists). Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowledge.

At a time when scholars were writing in Latin, Descartes wrote in French so anyone who was literate in the common language of his place could read his work. His writing style is friendly and approachable, so it feels as though you are having a conversation with him. His sceptical inquiry into what we can know commences with the question:

Can my senses be trusted?

Descartes describes himself sitting in front of a log fire in his wood cabin, smoking a pipe and questioning whether or not he can be sure that he is awake and alert as opposed to asleep and dreaming. How can we know the difference, he asks, when sometimes, in our dream state, we feel as though we’re awake even though we’re not?

Using the first person point of view, Descartes ponders on the fact that he tends to use his senses to be sure he exists and that the world around him is real, but the senses can sometimes be deceived. Our eyes often play tricks on us – as proven by any optical illusion – so how can we trust something that tricks us even once?

Cartesian scepticism (Cartesian being the adjective to describe the school of Decartes’ thought) concludes ultimately all I can be truly sure of is that I am a thinking thing. Descartes’ famously declared:

“Cogito ergo sum: I think therefore I am.”

Descartes posits the only thing I can be sure of is that I exist because even when I doubt that, there is an “I” doing the doubting. The “I” that thinks or doubts, must surely exist, he claims.

For Descartes the mind is more knowable than the body, and he equates the human Soul with the mind. For him, the mind is the essence of a person.

As a mathematician and a ‘natural scientist’ Descartes sought to prove that truths of the world were as immutable as rational, logical mathematic proofs. After he has proven that “I think, therefore I am” is as secure a foundation for knowledge as “1 + 1 = 2” Descartes goes on to use a thought experiment in order to consider whether we can be sure God exists.

The Evil Genius thought experiment

Descartes’ thought experiment of the evil genius asks us to imagine there exists, instead of an entirely good and powerful God, an entirely powerful, all-knowing Malevolent Demon. The idea here is that this Demon could make us think we are experiencing the world as it truly is, but we aren’t really. We could be tricked by this Evil Genius, and we may not be able to trust any knowledge we receive about the world from our senses. Ultimately Descartes relies upon an Ontological or Rational Argument to prove that God exists and if God exists, then we can trust our senses as God would not fool us in such a way as the Evil Demon might.

The incredibly powerful questions Descartes asks still inform many of our science fiction fears as we wonder whether or not the world truly is as it appears to us. We can still see the power of doubting and if we take this worry too seriously, we can imagine being paralysed with fear, unable to do anything! Many of us accept that our senses can be tricked but we know that we just have to go on trusting them anyway and hope for the best.

This sceptical method Descartes outlines whereby we check what we believe to be true and question what we assume to be real is useful if we think of it in terms of seeking evidence for the beliefs we are taught and the assumptions we hold. Considered in this way, Descartes offers us a great tool for self-reflection. However, if we take this thought experiment seriously we may never be sure that even we ourselves exist!

In the 18th century, David Hume suggested that even the assumption of an ‘I’ that doubts is an illusion. Hume says all we have to go on is a string of conscious experiences. Whether we are truly awake or dreaming right now is something we may not be able to answer with absolute accuracy, a doubt played out in famous films like The Matrix and Inception.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology