Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 19 MAY 2025

A few weekends ago, I made a parenting mistake. I didn’t realise in the moment. The penny didn’t drop, until a good friend made a comment afterwards.

My family was hosting a brunch with several other families. After a few hours in the noisy, sticky, fray, one of our kids asked to retreat. Sensing my hesitation, he pointed out that none of the other guests were of his age.

Partly in acknowledgement, and partly because the retreat he had in mind involved attacking the thistles taking over our front lawn, I let him slip away.

Shortly afterwards, sitting with a group of parents, watching syrup-crazed children run riot out the back, I explained his absence. One parent stopped me at the words “no one my age”. He was wondering, aloud, why age was relevant – let alone a reason to retreat.

The friend who stopped me was one who’d moved to Australia as an adult. He saw the culture he was living in, and the one he’d left, with the benefit of fresh, discerning eyes. Before he finished making it, I saw his point.

Why not expect our kids to socialise with others, regardless of age? Why not encourage them to enjoy the company of those younger than them, and the company of those older than them?

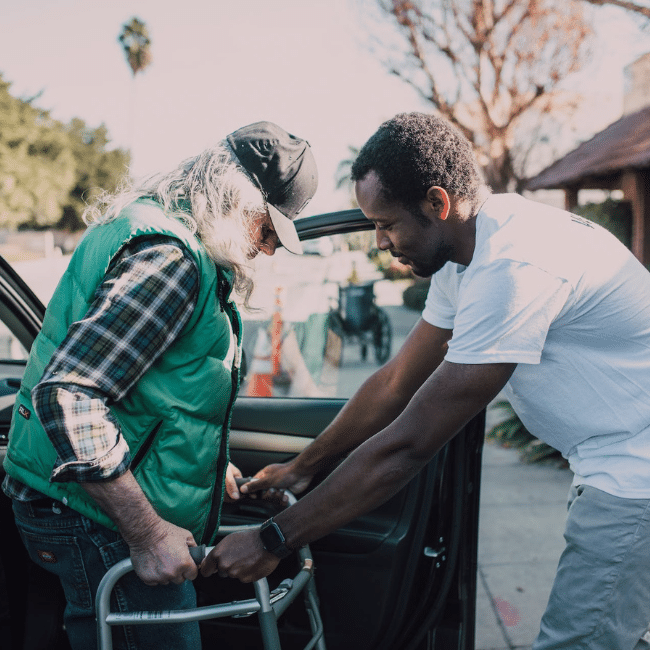

The friend in question told us he’d noticed this propensity to segregate by age before, and resolved not to succumb. He said he makes a point of crossing age divides, of greeting and conversing without discriminating, at social gatherings. Children, in particular, often seem puzzled by his attention. Sometimes they don’t return a greeting, or answer a question, they just stare. The stare might be translated to mean, “Why is this old dude talking to me?” or, “Why would I talk to this old dude?”. Sometimes they mutter something before running off, sometimes they just run off.

As the friend spoke, I recalled a social event where the child who’d just retreated had ended up deep in conversation with a grandparent he’d never met. I wished this image had come to mind earlier, prompted by the words “no one my age”. I knew both he and that grandparent had enjoyed their conversation, maybe as much as the cake, maybe more. It was proof age needn’t be a barrier.

Age needn’t be a barrier, but my friend’s description of children giving him quizzical looks when he acknowledges them suggests us adults are making it one. It suggests so few adults – not counting relatives – take the time to talk to them, that when one does it’s an anomaly.

I consider how much attention I pay to children who aren’t my own at social gatherings.

Sometimes, my attention is on fellow grown-ups and I don’t think to make an effort. At other times, I think to – then I overthink. I see a child and a compliment comes to mind but it’s based on their appearance, or a stereotype, so I censor myself. Or a question comes to mind, but the child in question is a teen and I imagine it will either induce a deep inward groan – “Not another adult asking what I’ll do post-school, how should I know?” – or defensiveness, or self-consciousness, or insecurity…

What lame excuses! If I want my kids to enjoy and initiate interactions and relationships with people of all ages, to throw age-related bias out the window, I should too – even if it requires a little bit of extra effort, creativity, or risk. Who cares if I induce an eye-roll or a groan? What matters is that I don’t just take a genuine interest, and show genuine interest, in adult’s lives, but in the lives of children, too.

I’m sure political philosopher David Runciman also attracts plenty of eye-rolls, as he did at last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas, when arguing that children as young as six should be allowed to vote. After acknowledging that many people find the idea laughable, he turns the question around. “Why shouldn’t they vote?” he asks. “They’re people; they’re citizens; they have interests; they have preferences; there are things that they care about.” Children might make irrational, ill-informed decisions, they might follow their tribe unthinkingly, they might dismiss facts that challenge pre-existing beliefs, but, he points out, adults might too.

“You can’t generalise about children any more than you can generalise about adults,” Runciman says, noting that being well-informed isn’t a prerequisite for voting. Being capable is, and six-year-olds, he argues, are.

Runciman speaks from experience – he once spent a term in an English primary school talking to kids as young as six about politics. Treating them “like they were full citizens”, he arranged for them to participate in the kind of focus groups political parties run for adults. The professional facilitator who ran them said one was among the most inspiring focus group sessions she’d ever been part of.

I’m not convinced children as young as six should be allowed to vote; I am convinced that when we assume we can’t learn from, or socialise with, or befriend them – when we widen the generational divide instead of closing it – we do ourselves and our society a disservice.

I was grateful, and I’m grateful still, that the friend who drew my attention to my parenting mistake didn’t let concern about how it might come across stop him from speaking his mind. Frank honesty is a quality some associate with children. Either way, it’s one that I admire.

I admired his persistence too – despite all those puzzled looks from kids, he’s persevered.

That persistence has paid off. It’s taken months, it’s taken years, but now some children run to him, or look for him at social gatherings. Now some consider him a friend.

For more, tune into David Runciman’s FODI talk, Votes for 6 year olds:

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why hard conversations matter

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY Tim Dean 19 MAY 2025

Arts organisations need to strengthen their ethical decision making and communication if they’re to avoid getting caught in controversy.

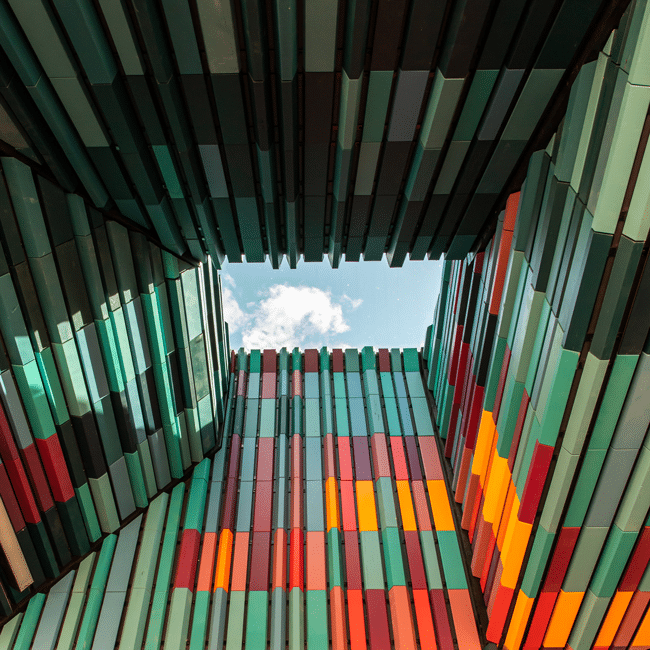

Which value should arts organisations prioritise? Artistic expression? Or the creation of safe and inclusive spaces, free from divisive issues and the possibility of offence? They often have to choose one because it’s impossible to prioritise both.

Yet, rightly or wrongly, arts organisations are facing demands that they promote both values, with some voices calling for them to prioritise safety at the expense of expression. The sheer impossibility of attempting to satisfy both values – or at least not failing in one of them and triggering a costly backlash – must be keeping the leaders of arts organisations across the country up at night.

There has always been an inherent tension between the values of artistic expression and safety (broadly defined), so there will inevitably be situations where maximising one will compromise the other. Push expression to the extreme and art can be dehumanising or promote hatred. Push safety to the fore and art would lose its power to challenge dominant narratives. This is why the arts have always had to balance the two, often leaning in favour of artistic expression, but with red lines that make things like bigotry or hate speech off-limits.

The challenge today is that we live in an increasingly fractious, polarised and volatile environment, where issues such as the conflict in Gaza are dividing communities and eroding trust and good faith. Where, in times past, onlookers might have treated an ambiguous artwork with charity, now they see endorsement of terror. Where an artist might once have been forgiven for making an off-hand remark in support of a humanitarian cause they believe in, they are now interpreted as promoting hate. This milieu has contributed to many voices – often powerful voices – calling to lower the bar for what is considered “unsafe” and, as a result, seeking to overly constrain expression.

How are arts organisations to continue to fulfil their mandate in such an environment? Given that the issues facing them are fundamentally ethical in nature, the answer comes in strengthening their ethical foundations. One way of doing that is formally adopting a clearly articulated set of values (what they think is good) and principles (the rules they adhere to) that become the sole standard for judgement when individuals make decisions on behalf of their organisation.

Couple that with robust processes for engaging in ethical decision making, and the organisation benefits from making better decisions – and avoiding hasty ones driven by panic or expedience – and is also better able to justify those decisions in the public sphere. There might still be some who criticise the decision, but even a cynic will be forced to acknowledge the consistency and integrity of the organisation.

Of course, arts organisations are not monolithic entities. Leaders and staff will inevitably vary in what they personally think is good and bad or right and wrong. And while individuals have a clear right to decide whether or not they will work with or support a particular organisation, no person can impose their own personal values and principles on those they work with. So, organisations need to have internal processes that allow this diversity to be acknowledged, while arriving at a single set of values and principles that can guide the organisation’s decisions.

And they need to do this without allowing “shadow values and principles” to subvert them. Many organisations have a lovely list of words pinned to the wall or splashed across the ‘About’ page on their website. But their internal culture promotes a different set of values by rewarding or punishing certain behaviours. As a result, it’s possible for an organisation to say it prioritises artistic expression but its actions show it values the patronage of wealthy supporters more, and it’s willing to compromise the former to satisfy the latter.

A truly ethical organisation will be self-aware enough to recognise shadow values and principles when they emerge, and a truly enlightened leadership will be able to redirect the culture towards promoting their stated values and principles.

All of this requires work. But it can be done. I have seen it first hand. I’ve worked with multiple arts organisations to help them better understand the values and principles that they wish to promote, and workshopped a range of scenarios to put its decision making processes to the test.

What would they do if an artist they’ve programmed posts something inflammatory on social media a week before they’re scheduled to perform? What if it was a controversial work from a decade ago? What are the red lines in terms of expression and what are they willing to defend? What would they do if a high-profile donor threatens to pull funding if they don’t deplatform an artist they object to? How should they treat an artist who uses the platform they’ve been given by the organisation to make a political comment unrelated to their work?

The organisations I’ve worked with have answers to these questions. The answers might not satisfy everyone, and they might involve compromises, but they are consistent with the values and principles that drive the organisation.

There may be no single correct answer to many of the ethical challenges that arts organisations face, but there are better and worse answers. Having a robust ethical framework and decision making processes won’t make arts organisations immune to controversy, but it will help them avoid much of it, and enable them to respond with integrity to whatever comes their way.

If you’re an individual or an organisation facing a difficult workplace decision, The Ethics Centre offers a range of free resources to support this process. We also offer bespoke workshops, consulting and leadership training for organisations of all sizes. Contact consulting@ethics.org.au to find out more.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

A radical act of transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

It’s time to consider who loses when money comes cheap

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership