Research shows that physical appearance can affect everything from the grades of students to the sentencing of convicted criminals – are looks and morality somehow related?

Ancient philosophers spoke of beauty as a supreme value, akin to goodness and truth. The word itself alluded to far more than aesthetic appeal, implying nobility and honour – it’s counterpart, ugliness, made all the more shameful in comparison.

From the writings of Plato to Heraclitus, beautiful things were argued to be vital links between finite humans and the infinite divine. Indeed, across various cultures and epochs, beauty was praised as a virtue in and of itself; to be beautiful was to be good and to be good was to be beautiful.

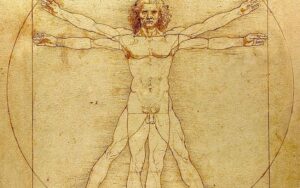

When people first began to ask, ‘what makes something (or someone) beautiful?’, they came up with some weird ideas – think Pythagorean triangles and golden ratios as opposed to pretty colours and chiselled abs. Such aesthetic ideals of order and harmony contrasted with the chaos of the time and are present throughout art history.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c.1490

These days, a more artificial understanding of beauty as a mere observable quality shared by supermodels and idyllic sunsets reigns supreme.

This is because the rise of modern science necessitated a reappraisal of many important philosophical concepts. Beauty lost relevance as a supreme value of moral significance in a time when empirical knowledge and reason triumphed over religion and emotion.

Yet, as the emergence of a unique branch of philosophy, aesthetics, revealed, many still wondered what made something beautiful to look at – even if, in the modern sense, beauty is only skin deep.

Beauty: in the eye of the beholder?

In the ancient and medieval era, it was widely understood that certain things were beautiful not because of how they were perceived, but rather because of an independent quality that appealed universally and was unequivocally good. According to thinkers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, this was determined by forces beyond human control and understanding.

Over time, this idea of beauty as entirely objective became demonstrably flawed. After all, if this truly were the case, then controversy wouldn’t exist over whether things are beautiful or not. For instance, to some, the Mona Lisa is a truly wonderful piece of art – to others, evidence that Da Vinci urgently needed an eye check.

Consequently, definitions of beauty that accounted for these differences in opinion began to gain credence. David Hume famously quipped that beauty “exists merely in the mind which contemplates”. To him and many others, the enjoyable experience associated with the consumption of beautiful things was derived from personal taste, making the concept inherently subjective.

This idea of beauty as a fundamentally pleasurable emotional response is perhaps the closest thing we have to a consensus among philosophers with otherwise divergent understandings of the concept.

Returning to the debate at hand: if beauty is not at least somewhat universal, then why do hundreds and thousands of people every year visit art galleries and cosmetic surgeons in pursuit of it? How can advertising companies sell us products on the premise that they will make us more beautiful if everyone has a different idea of what that looks like? Neither subjectivist nor objectivist accounts of the concept seem to adequately explain reality.

According to philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Francis Hutcheson, the answer must lie somewhere in the middle. Essentially, they argue that a mind that can distance itself from its own individual beliefs can also recognize if something is beautiful in a general, objective sense. Hume suggests that this seemingly universal standard of beauty arises when the tastes of multiple, credible experts align. And yet, whether or not this so-called beautiful thing evokes feelings of pleasure is ultimately contingent upon the subjective interpretation of the viewer themselves.

Looking good vs being good

If this seemingly endless debate has only reinforced your belief that beauty is a trivial concern, then you are not alone! During modernity and postmodernity, philosophers largely abandoned the concept in pursuit of more pressing matters – read: nuclear bombs and existential dread. Artists also expressed their disdain for beauty, perceived as a largely inaccessible relic of tired ways of thinking, through an expression of the anti-aesthetic.

Nevertheless, we should not dismiss the important role beauty plays in our day-to-day life. Whilst its association with morality has long been out of vogue among philosophers, this is not true of broader society. Psychological studies continually observe a ‘halo effect’ around beautiful people and things that see us interpret them in a more favourable light, leading them to be paid higher wages and receive better loans than their less attractive peers.

Social media makes it easy to feel that we are not good enough, particularly when it comes to looks. Perhaps uncoincidentally, we are, on average, increasing our relative spending on cosmetics, clothing, and other beauty-related goods and services.

Turning to philosophy may help us avoid getting caught in a hamster wheel of constant comparison. From a classical perspective, the best way to achieve beauty is to be a good person. Or maybe you side with the subjectivists, who tell us that being beautiful is meaningless anyway. Irrespective, beauty is complicated, ever-important, and wonderful – so long as we do not let it unfairly cloud our judgements.

Step through the mirror and examine what makes someone (or something) beautiful and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for the Ethics of Beauty on Thur 29 Feb 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture