Ethics Explainer: Ownership

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 5 JUL 2017

Where lying is the abuse of truth and harm the abuse of dignity, philosophers associate theft with the abuse of ownership.

We tend to take property for granted. People own things, share things or have access to things that don’t belong to them. We rarely stop to think how we come to own things, whether there are some things we shouldn’t be allowed to own or whether our ideas of property and ownership are adequate for everybody.

This is where English philosopher John Locke comes in.

Locke believed that in a state of nature – before a government, human made laws or an established economic system – natural resources were shared by everyone. Similar to a shared cattle-grazing ground called the Commons, these were not privately owned and so accessible to all.

But this didn’t last forever. He believed common property naturally transformed into private property through ownership. Locke had some ideas as to how this should be done, and came up with three conditions:

- First, limit what you take from the Commons so everyone else can enjoy the shared resource.

- Second, take only what you can use.

- Third, that you can only own something if you’ve worked and exerted labour on it. (This is his labour theory of property).

Though his ideas form the bedrock of modern private property ownership, they come with their fair share of critics.

Ancient Greek philosopher Plato thought collective property was a more appropriate way to unite people behind shared goals. He thought it was better for everyone to celebrate or grieve together than have some people happy and others sad at the way events differently affect their privately-owned resources.

Others wonder if it is complex enough for the modern world, where the resource gap between rich companies and poor communities widens. Does this satisfy Locke’s criteria of leaving the Commons “enough and as good”? He might have a criticism of his own about our current property laws – that they’ve gone beyond what our natural rights allow.

Some critics also say his theory denies the cultivation techniques and land ownership of groups like the Native Americans or the Aboriginal Australians. While Locke’s work serves as a useful explanation of Western conceptions of property ownership, we should wonder if it is as natural as he thought it was.

On the other hand, it’s likely Locke simply had no idea of the way in which Indigenous people have managed the landscape over millennia. Had he understood this, then he may have recognised the way Indigenous groups use and relate to land as an example of property ownership.

Karl Marx, and the closely associated philosophies of socialism and communism, prioritise common or collective property over private forms of property. He thought humanity should – and does – move toward co-operative work and shared ownership of resources.

However, Marx’s work on alienation may be a common ground. This is when people’s work becomes meaningless because they can’t afford to buy the things they’re working to make. They can never see or enjoy the fruits of their labour – nor can they own them. Considering the importance Locke places on labour and ownership, he may have had a couple of things to say about that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

READ

Business + Leadership

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

It’s time to consider who loses when money comes cheap

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

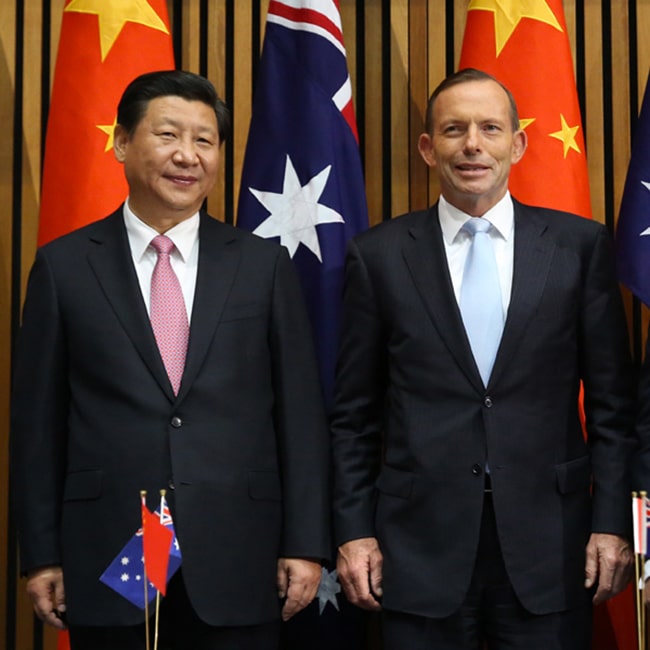

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership