It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Alliance 29 MAY 2023

In order establish more culturally diverse and inclusive workplaces, we need to increase our racial literacy.

We only need to look at the pay gap and underrepresentation in leadership to identify systemic racial issues within our organisations. In 2022, the Everyday Respect Report released from EB & Co identified racism as one of the factors impacting psychological safety and workplace culture. While new research from diversity and consultancy firm, MindTribes uncovered a non-Anglo pay gap within Australian organisations.

Workplace norms, systems and biases have sanitised racism to the point where not only it can affect individual’s mental wellbeing, pay and career progression, but also an organisation’s productivity, culture and consumer response. As ethical leaders we have a responsibility to unveil how racial discrimination plays out in our businesses and what strategies we can use to combat them.

An Ethics Exchange gathering in May 2023, welcomed Diversity Council of Australia (DCA) CEO Lisa Annese and Ethics Alliance members as they shared personal experiences and strategies used when developing Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) programs, and how they recognise and tackle racism within their workplaces.

The DCA has evolved over the last 40 years to become a leading entity which promotes and advances more diverse and inclusive workplaces for the benefit of individuals, organisations and the broader community. Annese says to build strategies that tackle racism in our organisations, we need to start with language.

Let’s start with language

It’s important to understand the difference in language when it comes race and culture, particularly within the Australian D&I context. Culture is defined as a combination of characteristics including ethnicity, ancestry, language, and place of origin, whereas race is generally seen as a social construct related to physical characteristics and group identity.

In response to the White Australian policy there was an effort by Gough Whitlam in the late 1960s to remove “race” from common language in order to reduce racism. This shift resulted in a focus on culture over race, and the country adopted terms such as “non-English speaking background”, embracing the concept of multiculturalism. For instance, since the United Nations created their Elimination of Racial Discrimination Day, Australia is the only country globally that doesn’t use the word race. We instead call it Harmony Day with a focus on harmony for the week. That is what is taught in our public schools and celebrated in our workplaces.

Annese suggests this avoidance of the term “race” in favour of “culture” was also an effort to maintain an existing Eurocentric power structure. For example, the term “culturally and linguistically diverse” was introduced, which broadly referred to anyone who couldn’t trace their origins back to Britain – essentially anyone non-Anglo Celtic. This excludes a large group of people with different experiences and perpetuates a sense of “otherness.”

Once we identify the other it can become easy to treat people differently and not afford them the same respect we would expect ourselves.

While understanding people’s culture is useful, it’s crucial to talk about race and to acknowledge the lived experiences of Australians who experience racism.

DCA research suggests that in Australia today, those who experience racism and racial marginalisation are people from non-European backgrounds, and the main cause of racism has less to do with language and culture and focuses more on race – features such as phenotype, visible difference, religious dress, skin tone, and hair texture.

If we want to build more inclusive and diverse businesses, we need to talk about race. And to do so, we must know what it is.

By developing an understanding of how history has sanitised our language and normalised racism in our workplace, we are able to discuss the concept of race in a way that avoids unnecessary distress. It’s important not to make assumptions that the harm felt by malintent, or overt racism is any different from the racism embedded in well-meaning or curious comments about an individual’s appearance or background.

Principles and a framework that emerged from The Ethics Exchange and DCA research to bring racial literacy to the workplace included:

- Build Racial Literacy: Before tackling racism, businesses must first educate their employees about the concept of race. They should understand what race is, how racialisation occurs, and the impact it has on people. This is important because most people have low levels of racial literacy.

- Build Confidence: The second step involves helping employees become confident in their understanding of race and racial issues. This stage ensures employees feel comfortable discussing these topics and are prepared for the next step.

- Talk About Anti-Racism: The final stage is to discuss what it means to be actively anti-racist. It is important that employees understand how they can contribute to an anti-racist environment. This stage of the process can only be effectively implemented once employees have a clear understanding of race and are confident discussing it.

One of the most impactful ways of understanding racism is to hear it from those who have been subject to it, however this carries a huge burden or cultural load. How can their voices be included to develop strategies to combat racism?

- Centre Voices: The experiences and perspectives of those affected by racism must be central to any initiatives addressing it. For instance, if a business is developing a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) in Australia, it should involve Indigenous employees in the process.

- Respect Cultural Labour: Organisations should acknowledge the cultural emotional and intellectual labour of employees with different social identities involved in initiatives addressing racism.

- Remunerate Appropriately: If individuals are asked to participate in initiatives to combat racism, particularly if they’re asked to share personal experiences or provide additional insights, they should be appropriately compensated.

- Respect Personal Choice: Not everyone will want to be involved in such initiatives, and that choice should be respected.

- Avoid Overgeneralisation and Presumption: One individual cannot represent an entire group. Avoid making assumptions about an entire race or culture based on the perspectives or experiences of one individual.

- Use Available Resources: In an age where information is readily available, it’s possible to educate oneself about different cultures and races without overly relying on individuals from those backgrounds to teach others.

We’d like to thank Lisa Annese and the Ethics Alliance members who contributed to this important conversation.

Find out more about the DCA’s research here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

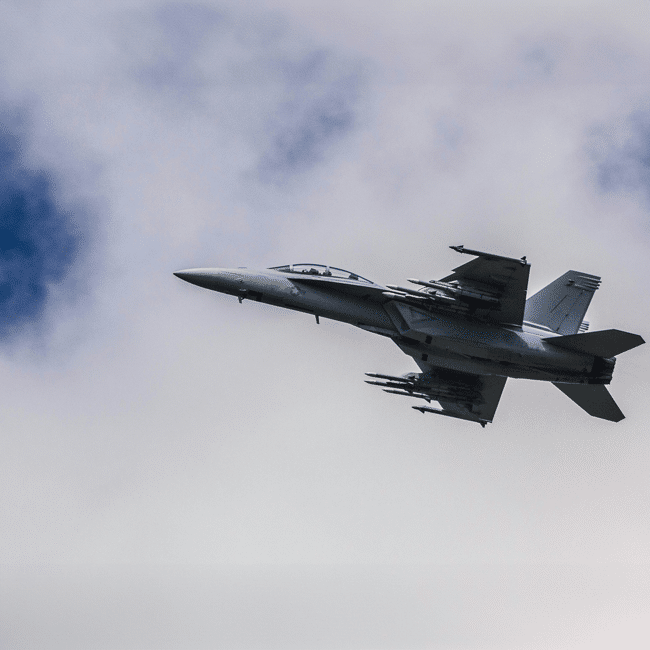

Politics + Human Rights

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture