Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith 1 JAN 2018

Nick Naylor is a man who is comfortable being despised. In the movie Thank You for Smoking, he is the spokesman for the tobacco lobby and happily admits he fronts an organisation responsible for the deaths of 1,200 people every day.

While he excuses his employment as a lobbyist by unconvincingly adopting the “Yuppie Nuremberg defence” of having to pay a mortgage, the audience learns that his real motivation is that he loves to win.

The bigger the odds, the better.

Naylor is not the sort of man who would struggle with ethical distress or moral injury from the work he chooses to do. This work “requires a moral flexibility that is beyond most people”, he says.

He likens his role to that of a lawyer, who has to defend clients whether they are guilty or not.

Partner of law firm Maurice Blackburn, Josh Bornstein, says the convention in law that everyone deserves legal representation can certainly assist lawyers called upon to defend people whose actions they find morally reprehensible – however that argument does not work for everyone.

‘If I don’t, someone else will’

Bornstein says there is no way of knowing how many lawyers refuse to work on cases because of moral conflict, but it happens from time to time. “Not every week or every month”, he adds.

“Do [lawyers] have moral crises? Some people have a strong sense of morality and others try and sweep that to one side and consider that, as professional lawyers, they shouldn’t dwell on moral concerns”, says Bornstein, who specialises in workplace law.

Bornstein is well known for his advocacy for victims of bullying and harassment, however, he has also acted for people accused of those things.

“I’ve found myself, from time to time, acting in matters that have been very morally confronting”, he says.

As a young lawyer, when he was expressing his disapproval of the actions of a client, his mentor told him to stop moralising and indulging himself.

“He said that when people like that get into that trouble, that is the time they need your assistance more than any other. Your job is to help them, even when they have done the wrong thing”, says Bornstein.

Bornstein says ethical distress can occur in all sorts of professions. “I would think the same would occur for a psychologist, social worker, doctors, and maybe even priests.

“Consider the position if you were lawyers for the Catholic Church over the last three decades, dealing with horrific, ongoing cases of child sexual abuse.”

Distress or injury? Making a distinction

The CEO of Relationships Australia NSW, Elisabeth Shaw, says when seeking to understand the psychological damage wrought by such conflicts, a distinction should be made between ethical (or moral) distress and moral injury.

Ethical or moral distress occurs when someone knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.

This definition is often used in nursing, where staff are conflicted between doing what they feel is right for the patient and what hospital protocol and the law allows them to do. They may, for instance, be required to resuscitate a terminally ill patient who had expressed a desire to end the pain and die in peace.

Moral injury is a more severe form of distress and tends to be used in the context of war, describing “the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioural, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations”.

The St John of God Chair of Trauma and Mental Health at the University of New South Wales, Zachary Steel, says most moral injuries stem from “catastrophic traumatic encounters”, such as military and first responder types of duties and responsibilities.

He says he sees moral injury as a variant of post-traumatic stress disorder and distinguishable from the kind of moral harm wrought by bullying and highly dysfunctional workplaces.

Tainted by your compliance

This distinction does not diminish the distress experienced by those who are torn between what they are expected to do, and what they know they should do.

Shaw, who has volunteered at The Ethics Centre’s Ethi-call hotline for eight years as team supervisor, says the service handles around 1,500 calls per year and a typical request for advice may come from an accountant who is pressured to sign off on dodgy records.

“After [complying], you may feel a lesser version of yourself. You may feel you didn’t have a choice, but also feel quite tainted by those actions”, she says.

“Even if you went to great lengths to do all the things that could be seen to be correct, you can still feel very injured at the end of it.”

For some people, it is the nature of the organisation they work for, or its culture, that creates a problem.

“Some people feel like they are part of an organisation that is, perhaps, habitually part of shabby behaviour”, says Shaw.

Someone working for a tobacco company (like the fictional Nick Naylor) may start by shrugging off concerns, reasoning that they need the job and if they don’t do it, someone else will. However, over time, embarrassment grows and they become more aware of the disapproval of others and they start to feel morally compromised, says Shaw.

“And then there is a point where it feels like [your job] has injured your sense of self … or even your professional identity and, in fact, might make you feel less than yourself.”

There are also professions where people sign up for noble reasons, in a not-for-profit, for instance, but then find unjustifiable things are happening.

“You start to feel like there is a huge dissonance – that can no longer be resolved – between what you say you are doing and what you are actually caught up in.”

Can’t tell right from wrong

Burnout and mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression can result from this stress and some people become so ethically compromised they lose their moral compass and no longer can tell right from wrong, she says.

Moral distress is one of a range of factors contributing to the poor record of the law profession when it comes to the incidence of mental health issues, says Bornstein.

A third of solicitors and a fifth of barristers are understood to suffer disability and distress due to depression.

Some of the more “sophisticated” firms encourage their people to seek assistance and offer employee assistance programs, such as hotlines.

Maurice Blackburn has a “vicarious trauma program” for lawyers who may, for instance, work with people dying from asbestosis or medical mishaps or accidents.

“Even in my area of employment [workplace law], vicarious trauma is a real risk and problem”, he says.

“So, we have tried to change our culture to be very open about it, speak about it, to regularly review it, to work with psychologists, to have a program to deal with it, to know what to do if a client threatens suicide or self-harm. But it is an ongoing challenge.”

Bornstein has, himself, sought guidance from the Law Institute on ethical dilemmas.

“The other underestimated, fantastic outlet is to confer with colleagues you respect who are, hopefully, one step or more removed from the situation and can give wise counsel. Another is to seek similar support from barristers, I’ve done that too, and then there is friends and family.”

Bornstein says even though he is not aware of any law firm offering a “moral repugnance policy” that would allow people to avoid working on cases that could cause ethical distress, he is aware there would be little benefit in forcing a lawyer to take one.

“It may be resolved by [getting] someone else working on the case.”

The value of a strong ethical framework

Social work is another area that is fraught with ethical dilemmas and, like lawyers, social workers often see people at their worst.

However, the profession has a developed an ethical framework and support system that ensures workers are not left alone to tackle difficult dilemmas, says Professor Donna McAuliffe, who has spent the past 20 years teaching and researching in the area of social work and professional ethics.

“The decisions that social workers have to make can be very complex and distressing if they are not made well”, says McAuliffe, who is Deputy Head of School at the School of Human Services and Social Work at Griffith University.

Social workers have a responsibility, under their code of ethics, to engage professional supervision provided by their employer.

Because social work in Australia is a self-regulated profession, it is important to have a very robust and detailed code of ethics to give guidance around practise, she says.

“We educate social workers to not go alone with things, that consultation and support of colleagues are going to be the best buffers against burn out and distress and falling apart in the workplace – and there is evidence to show good collegial, supportive relationships at work is the thing that buffers against burnout in the best way.”

McAuliffe says employers in business may think about building into their ethical decision making frameworks some consideration of the emotions, worldview, and cultures of the people affected by difficult workplace choices.

“The decision may still be the same … but the [employee] will feel a hell of a lot better about it if they know they have thought about how the person at the end of that decision can be supported.”

Shaw cautions that people should try and seek other perspectives before making decisions about situations that make them feel morally uncomfortable.

“Part of the process of ethical reflection is to work out, ‘Do I have a point?’

“Because we are all developed in different ways ethically, just because you have a reaction and you are worried about something and you feel ethically compromised doesn’t make you correct.

“What it means is that your own moral code feels compromised. The first thing to do is spend some time working out, is my point valid? Do I have all the facts?

“What do I do about the fact that my colleagues and bosses don’t feel bothered? Should I look at their point of view?

“Sometimes, when you feel like that, it really is a trigger for ethical reflection. Then, on the basis of your ethical reflection, you might say, ‘You know what? Now that I have looked at it from many angles, I think, perhaps I was over-jumpy there and I think if I take these three steps, I could probably iron this out, or if I spoke up, change might happen.’

“And then the whole thing can move on.

“Having a reaction to what feels like an ethical trigger is really just the beginning of a process of self-understanding and the understanding in context.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

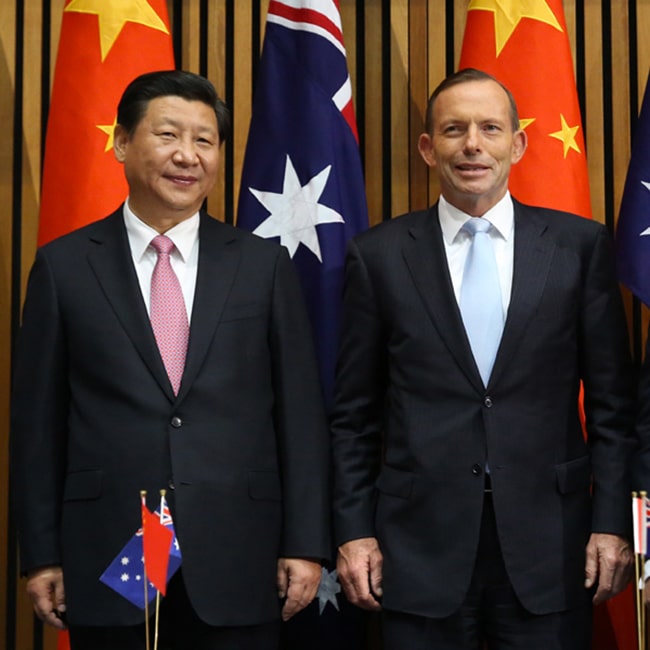

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership