The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipClimate + Environment

BY Isabella Vacaflores 22 MAR 2022

Consumer responses are crucial to holding businesses accountable for their social and environmental responsibilities.

As of this year, over half of the highest polluting companies in Australia have committed to net-zero emissions targets. Meanwhile, in the Twitter-verse, dating apps and chocolate bars proclaim an end to police brutality, sexism, and the Uighur genocide.

Out of nowhere, big business has seemingly grown a social consciousness – and an impressive marketing budget to match. From fast fashion to mining, you’d be hard-pressed to find a company that doesn’t claim to be doing the right thing by their employees and the environment.

Moral grandstanding: When businesses fail to put their money where their mouth is

Unfortunately, a lot of this moral messaging is nothing more than opportunistic marketing, designed to profit from a societal shift towards conscious consumption. As recent reporting by Greenpeace highlights, of those Australian companies that claim to be going green, only a small fraction are actually taking effective steps by switching to cleaner energy sources.

Likewise, many brands divert attention from dubious business operations by aligning themselves with the popular side of trending moral discourse, tweeting out support for social justice movements while simultaneously being accused of the very issues they rally against. As in the following advertisement, which seemingly suggests that the solution to America’s police brutality problem is drinking Pepsi, even at best case, such messaging can come across as offensively tone-deaf.

This phenomenon is what philosophers Justin Tosi and Brandon Warmke describe as ‘moral grandstanding’ – the insincere use of principled arguments to self-promote or seek status. Similarly, the terms ‘virtue signalling’, ‘performative activism’, ‘green-washing’ and ‘woke capitalism’ describe how moral concerns can be deployed as a front for self-serving behaviour.

Ultimately, all these phrases describe the same thing, which is the failure of businesses to practice what they preach.

This hypocrisy is a problem because it prevents meaningful change from occurring while simultaneously misleading consumers into believing that we are well on the way to a better world when actually, progress flounders.

Doing something is better than doing nothing, except when it isn’t

Consequentialism asserts that actions are good if they cause more benefit than harm. Using this line of reasoning, many argue that insincerity is a small price to pay for having big business commit to less harmful commercial practices, which diminishes moral grandstanding to a largely trivial concern.

Yet, when we contemplate the opportunity cost of accepting such half-baked behaviour from those who have the most power to affect change, this argument quickly becomes self-defeating. Consider what would happen if businesses diverted the money and resources spent on advertising their moral character towards researching and enacting reforms that put substance behind these self-proclaimed progressive values.

As consumers, we cannot accept anything less than this because to do so would cause our planet and people to needlessly suffer – a harm that far outweighs any benefit gained from morally grandstanding promises to “do better”.

Additionally, from a deontological perspective, it can be argued that the intention behind moral actions is what truly determines their worth. Since morally grandstanding companies aren’t motivated by a principled duty, but rather, by a profit outcome, they can hardly be considered good (in a Kantian sense, anyway).

How to spot a moral grandstander

In the past half-decade, energy giant AGL has heavily advertised their pledge to decarbonise while simultaneously remaining Australia’s largest greenhouse emitter. Meanwhile, companies such as Woolworths, Coles and Telstra have quietly gotten on with transitioning to almost 100 per cent renewable energy.

Greenpeace campaign takes aim at AGL. Image by Monster Children Creative

Evidently, some businesses are being genuine with their environmental and social commitments. The problem with moral grandstanders is that they take the spotlight away from such efforts. As consumers, we can have a meaningful impact on our world by choosing to spend our money with the former, but the question remains of how to distinguish between the two:

- Consumers can start by asking themselves about the nature of the company which is making the moral appeal –are harmful business practices embedded in the industry they operate in? Does the business themselves have a poor social or environmental track record? If the answer to either of these questions is ‘yes’, then their claims should be viewed suspiciously.

- Be on the lookout for weasel words – buzz-wordy claims which are deliberately vague. Saying something is “green” or “eco-friendly” isn’t a qualifiable statement. Also, note that the validity of some credentials relating to fair trade and carbon emissions are being increasingly challenged.

- As with any investment, if you’re going to put your money into a business based on their moral claims, fact-checking is always a good idea. This can be done through a quick internet search or a skim through related news results.

Remember that in many countries (including Australia), consumer rights laws exist to ensure companies cannot get away with making false claims about their products. Holding businesses to account for their moral grandstanding is therefore not just an ethical imperative – but a legal one also.

Kendall Jenner advertisement and images courtesy of Pespi

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

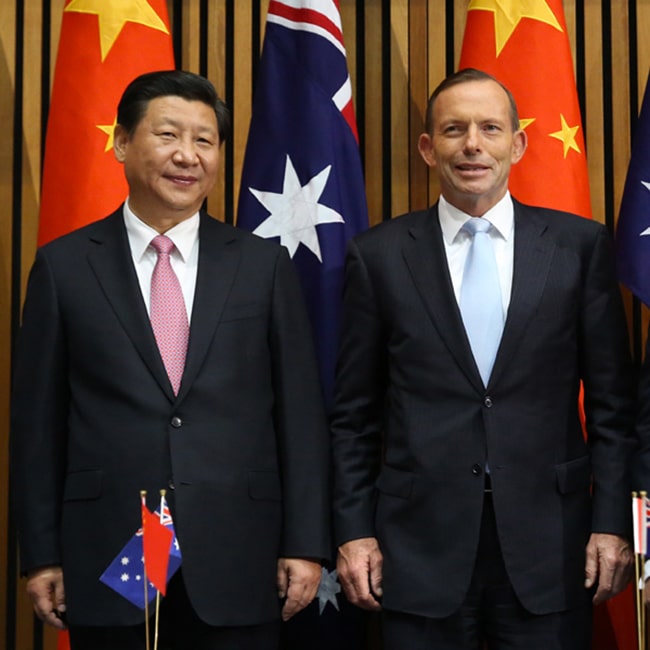

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Hindsight: James Hardie, 20 years on

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership