The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 15 DEC 2023

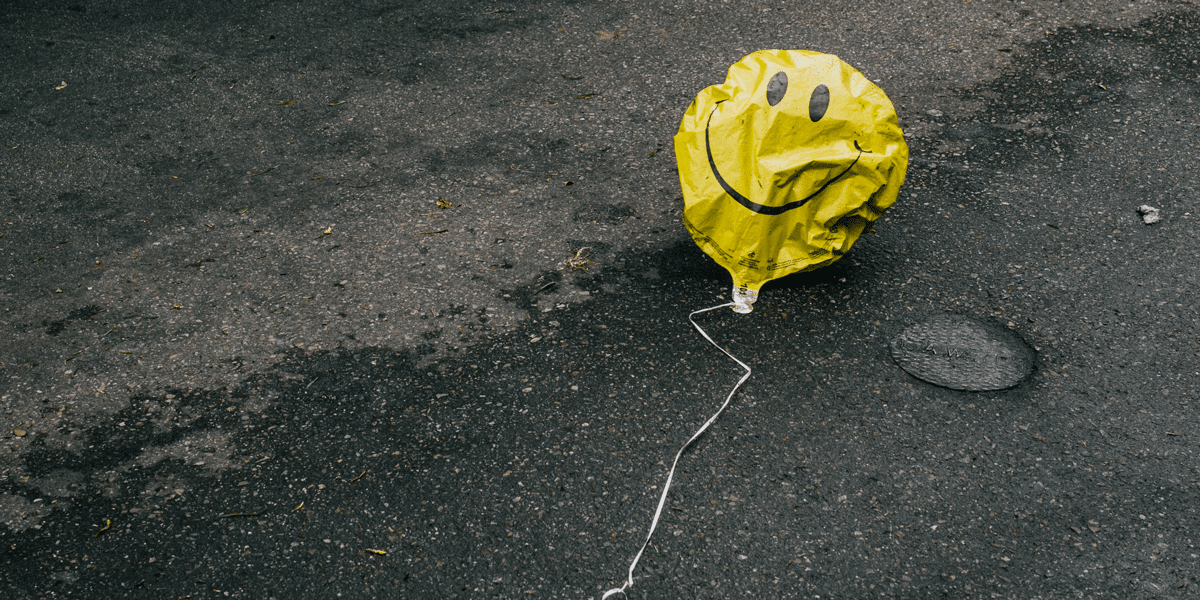

Can we be too nice? On the surface, it seems absurd to say we should put a cap on how nice we should be. But if we overdo it, we can end up shirking our other ethical obligations.

Skim the headlines or scroll through social media and you’d be forgiven for concluding that there’s a serious deficit of niceness in the world today, and if only people were a little more kind, compassionate and giving, then the world would be a much better place.

Imagine a nicer world where other drivers consistently backed off to let you merge lanes, or shrugged off your occasional failure to check a blind spot with a smile and a wave. Imagine a workplace where everybody lifted each other up, and covered for you when you needed a break. Imagine a world with more Dumbledores and fewer Snapes. Imagine a world without Karens.

Most philosophers have sought such a world by urging us to cultivate niceness. Confucious promoted the foundational virtue of ren, often translated as benevolence or humanity. Aristotle argued that the path to flourishing lay in cultivating virtues like magnanimity, generosity and patience. Christian scholars promoted temperance was a cardinal virtue. In more modern times, Peter Singer has said we ought to take the compassion we feel towards close family and friends and expand it to cover all sentient creatures, human and animal. In short: be nice.

But there’s also a catch with niceness. If we take it to excess, we can leave ourselves vulnerable to exploitation, fail in our ethical duties and even undermine the very moral foundations of our community.

This is because a world where everyone is fully trusting and selflessly giving is a ripe hunting ground for those who are willing to abuse that trust and get ahead by stepping on the backs of others.

The paradox of niceness

This phenomenon can be modelled using the popular game theoretic thought experiment, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine a situation where two bank robbers are arrested and held in separate cells, unable to communicate with each other. The police have no other witnesses, so they’re relying on the suspects’ testimony to prove the case against them. If both suspects confess, they’ll both receive a five-year sentence. If they both remain silent, then the police will only be able to charge them with a minor offense carrying a one-year sentence. However, if one of them testifies while their partner remains silent, then the dobber will be set free while their partner will go to jail for 10 years.

On the surface, it seems sensible for them both to remain silent. That would be the “nice” thing to do because it benefits them both. But there’s a twist. If one of the suspects believes that their partner will remain silent, then they have an opportunity to testify against them and get off scott-free, while their partner is thrown in the slammer. They also know that if they remain silent, then their partner will have an opportunity to dob them in. As a result, the most reasonable thing for either of them to do is dob on the other, which means they both end up with a harsher penalty than if they’d both cooperated and stayed silent.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma models a fundamental truth when it comes to social interaction: if we we’re nice, we all benefit, but there will always be a temptation to exploit the charity of others to get ahead, and in doing so, we can end up destroying the possibility of cooperation altogether.

There have been whole virtual tournaments using the Prisoner’s Dilemma to see what kinds of strategies – whether “nice” or “nasty” – will yield the best results for the agents playing the game. And it’s from these tournaments that another twist emerges.

In a single Prisoner’s Dilemma game, the nasty dobber has the upper hand, especially if their partner is nice. However, when the same agents play the game over and over, it turns out that it pays to be nice, because you’re likely to be punished in the next game if you’ve been nasty. When you add in some real-world flavour to the game, like making it so that agents can sometimes mistakenly defect when they meant to cooperate, it’s the nicer agents that come out on top.

But these simulations show that niceness has its limits. Those agents that are unconditionally nice tend to get exploited by nasty ones. However, those strategies that are conditionally nice, and that defect only to punish bad behaviour, do best of all.

Toxic niceness

Back in the real world, what this means is that it is possible to be too nice. If we’re unconditionally generous and forgiving, then we leave ourselves open to exploitation by people who will take advantage of our niceness.

It’s likely we all know someone who is a natural giver, someone whose empathy is overflowing and who goes out of their way to help everyone around them. These people are often much loved, but they can also be crushed under the weight of their own compassion, sometimes neglecting their own wellbeing, and it’s not uncommon for others to take advantage of their generosity.

Such unconditional niceness can also prevent us from punishing those who deserve it. You may have also worked for a manager who was overly forgiving, not only of minor transgressions, but also behaviour that was toxic or harmful to others. Punishment is inherently unpleasant, and the overly nice can be reluctant to mete it out, staying their hand while wrongdoers run amok. That not only undermines the moral community, but it makes it harder to hold people to account for their actions, preventing them from growing by learning from their mistakes.

Niceness is good. Be nice. But not so nice that you allow others to be nasty.

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture