Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

ExplainerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JUL 2021

Imagine waking up in a bed, disoriented, bleary-eyed and confused.

You can’t remember how you got to there, and the bed you’re in doesn’t feel familiar. As you start to get a sense of your surroundings, you notice a bunch of medical equipment around. You notice plugs and tubes coming out of your body and realise you’re back-to-back with another person.

A glimpse in the mirror tells you the person you’re attached to is a world-famous violinist – one with a fatal kidney ailment. And now, you start to realise what’s happened. Last night, you were invited to be the guest of honour at an event hosted by the Society of Music Lovers. During the event, they told you about this violinist – whose prodigious talent would be taken from the world too soon if they couldn’t find a way to fix him.

It looks like, based on the medical records strewn around the room, the Society of Music Lovers have been scouring the globe for someone whose blood type and genetic markers are a match with the violinist.

A doctor enters the room, looking distressed. She informs you that the Society of Music Lovers drugged and kidnapped you, and had your circulatory system hooked you up to the violinist. That way, your healthy kidney can extract the poisons from the blood and the violinist will be cured – and you’ll be completely healthy at the end of the process. Unfortunately, the procedure is going to take approximately 40 weeks to complete.

“Look, we’re sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you–we would never have permitted it if we had known,” the doctor apologises to you. “But still, they did it, and the violinist is now plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it’s only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment and can safely be unplugged from you.”

After all, the doctor explains, “all persons have a right to life, and violinists are persons. Granted you have a right to decide what happens in and to your body, but a person’s right to life outweighs your right to decide what happens in and to your body. So you cannot be unplugged from him.”

This thought experiment originates in American philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson’s famous paper ‘In Defence of Abortion’ and, in case you hadn’t figured it out, aims to recreate some of the conditions of pregnancy in a different scenario. The goal is to test how some of the moral claims around abortion apply to a morally similar, contextually different situation.

Thomson’s question is simple: “Is it morally incumbent on you to accede to this situation?” Do you have to stay plugged in? “No doubt it would be very nice of you if you did, a great kindness. But do you have to accede to it?” Thomson asks.

Thomson believes most people would be outraged at the suggestion that someone could be subjected to nine months of medical interconnectedness as a result of being drugged and kidnapped. Yet, Thomson explains, this is more-or-less what people who object to abortion – even in cases where the pregnancy occurred as a result of rape – are claiming.

Part of what makes the thought experiment so compelling is that we can tweak the variables to mirror more closely a bunch of different situations – for instance, one where the person’s life is at risk by being attached to the violinist. Another where they are made to feel very unwell, or are bed-ridden for nine months… the list goes on.

But Thomson’s main goal isn’t to tweak an admittedly absurd scenario in a million different ways to decide on a case-by-case basis whether an abortion is OK or not. Instead, her thought experiment is intended to show the implausibility of the doctor’s final argument: that because the violinist has a right to life, you are therefore obligated to be bound to him for nine months.

“This argument treats the right to life as if it were unproblematic. It is not, and this seems to me to be precisely the source of the mistake,” she writes.

Instead, Thomson argues that the right to life is, actually, a right ‘not to be killed unjustly’.

Otherwise, as the thought experiment shows us, the right to life leads to a situation where we can make unjust claims on other people.

For example, if someone needs a kidney transplant and they have the absolute right to life – which Thomson understands as “a right to be given at least the bare minimum one needs for continued life” – then someone who refused to donate their kidney would be doing something wrong.

Thinking about a “right to life” leads us to weird conclusions, like that if my kidneys got sick, I might have some entitlement to someone else’s organs, which intuitively seems weird and wrong, though if I ever need a kidney, I reserve the right to change my mind.

Interestingly, Thomson’s argument – written in 1971 – does leave open the possibility of some ethical judgements around abortion. She tweaks her thought experiment so that instead of being connected to the violinist for nine months, you need only be connected for an hour. In this case, given the relatively minor inconvenience, wouldn’t it be wrong to let the violinist die?

Thomson thinks it would, but not because the violinist has a right to use your circulatory system. It would be wrong for reasons more familiar to virtue ethics – that it was selfish, callous, cruel etc…

Part of the power of Thomson’s thought experiment is to enable a sincere, careful discussion over a complex, loaded issue in a relatively safe environment. It gives us a sense of psychological distance from the real issue. Of course, this is only valuable if Thomson has created a meaningful analogy between the famous violinist and what an actual unwanted pregnancy is like. Lots of abortion critics and defenders alike would want to reject aspects of Thomson’s argument.

Nevertheless, Thomson’s paper continues to be taught not only as an important contribution to the ethical debate around abortion, but as an excellent example of how to build a careful, convincing argument.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

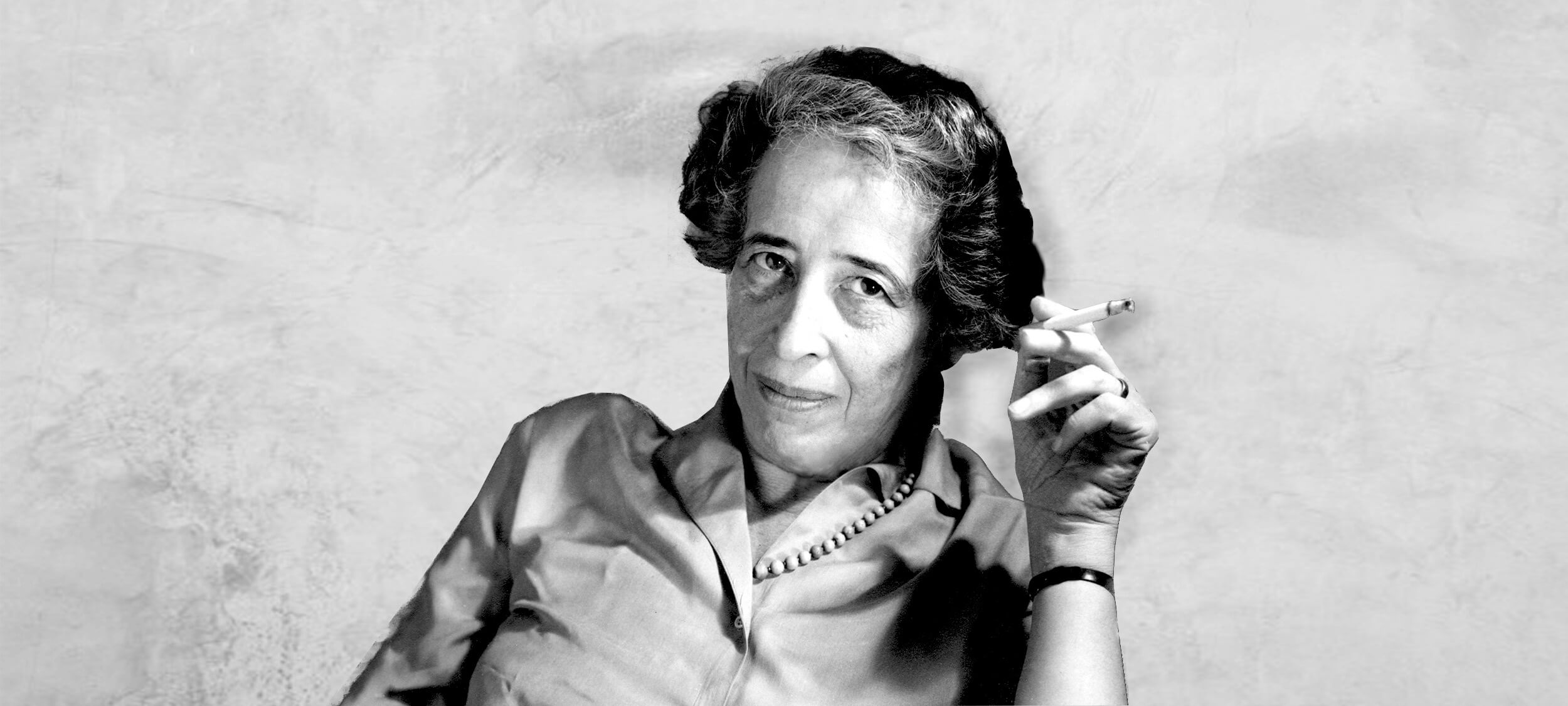

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights