Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 8 FEB 2024

How a 1990s science-fiction show reminds us that just because we can do something, it doesn’t always mean we should.

Captain Jean-Luc Picard commands the USS Enterprise-D, a 600-metre-long starship that runs on antimatter, giving it virtually unlimited energy, and wielding weapons of devastating power.

In its journeys across the stars, depicted in Star Trek: The Next Generation, the crew of the Enterprise-D is often forced to draw on all its resources to overcome tremendous challenges. But that’s not what the show is really about.

If there’s one theme that pervades this iteration of Star Trek, it’s not how Picard and his crew use their prodigious power to get their way, it’s how their actions are more often defined by what they choose not to do. Countless times across the 176 episodes of the show, they’re faced with an opportunity to exert their power in a way that benefits them or their allies, but they choose to forgo that opportunity for principled reasons. Star Trek: The Next Generation is a rare and vivid depiction of the principle of ethical restraint.

Consider the episode, ‘Measure of a Man’, which sees Picard defy his superiors’ order to dismantle his unique – and uniquely powerful – android second officer, Data. Picard argues that Data deserves full personhood, despite his being a machine. This is even though dismantling Data could lead to the production of countless more androids, dramatically amplifying the power of the Federation.

One of the paradigmatic features of The Next Generation is its principle called the Prime Directive, which forbids the Federation from interfering with the cultural development of other planets. While the Prime Directive is often used as a plot device to introduce complications and moral quandaries – and is frequently bent or broken – its very existence speaks to the importance of ethical restraint. Instead of assuming the Federation’s wisdom and technology are fit for all, or using its influence to curry favour or extract resources from other worlds, it refuses to be the arbiter of what is right across the galaxy.

This is an even deeper form of ethical restraint that speaks to the liberalism of Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s creator. The Federation not only guides its hand according to its own principles, but it also refuses to impose its principles on other societies, sometimes holding back from doing what it thinks is right out of respect for difference.

The 1990s was another world

There’s a reason that restraint emerged as a theme of Star Trek: The Next Generation. It was the product of 1990s America, which turned out to be a unique moment in that country’s history. The United States was a nation at the zenith of its power in a world that was newly unipolar since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It was an optimistic time, one that looked forward to an increasingly interconnected globalised world, where cultures could intermix in the “global village,” with its peace guarded by a benevolent superpower and its liberal vision. At least, that was the narrative cultivated within the US.

In a time where the US was unchallenged, moral imagination turned to what limits it ought to impose on itself. And Star Trek did what science fiction does best: it explored the moral themes of the day by putting them to the test in the fantasy of the future.

Today’s world is different. It’s now multipolar, with the rise of China and belligerence of Russia coinciding with the erosion of America’s power, political integrity and moral authority. The global outlook is more pessimistic, with the shadow of climate change and the persistence of inequality causing many to give up hope for a better future. Meanwhile, globalisation and liberalism have retreated in the face of parochialism and authoritarianism.

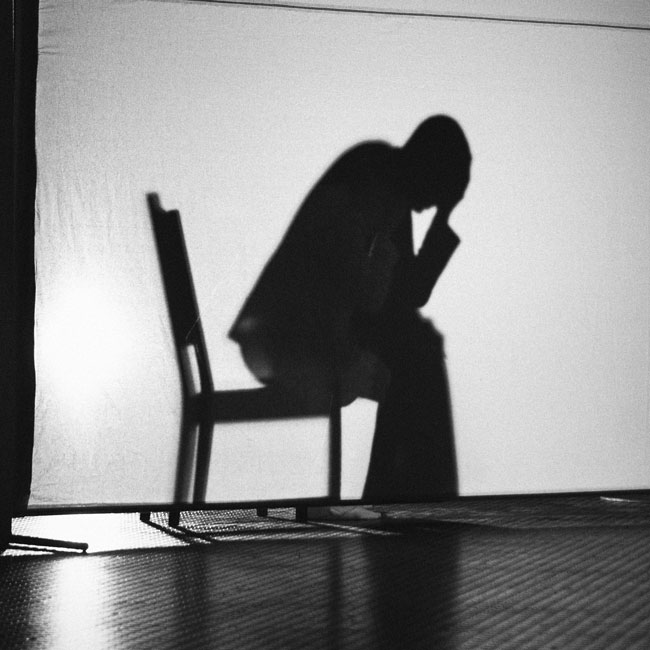

When we see the future as bleak and feel surrounded by threats, ethical restraint seems like a luxury we cannot afford. Instead, the moral question becomes about how far we can go in order to guard what is precious to us and to keep our heads above literally rising waters.

The power not to act

Yet ethical restraint remains an important virtue. It’s time for us to bring it back into our ethical vocabulary.

For a start, we can change the narrative that frames how we see the world. Sure, the world is not as it was in the 1990s, but it’s not as bleak as many of us might feel. We can be prone to focusing on the negatives and filling uncertainties with our greatest fears. But that can distort our sense of reality. Instead, we should focus on those domains where we actually have power, as do many people living in wealthy developed countries like Australia.

And we should use our power to help lift others out of despair, so they’re not in a position where ethical restraint is too expensive a luxury. Material and social wealth ultimately make ethics more affordable.

Just as importantly, restraint needs to become part of the vocabulary of those in positions of power, whether that be in business, community or politics.

Leaders need to implicitly understand the crucial distinction between ought and can: just because they can do something, it doesn’t mean they should.

This is not just a matter of greater regulation. For a start, laws are written by those in power, so they need to exercise restraint in their creation. Secondly, regulation often sets a minimum floor of acceptable behaviour rather than setting bar for what the community really deserves. It also requires ethical literacy and conviction to act responsibly within the bounds of what is legally permitted, not just a tick from a compliance team.

If you have power, whether you lead a starship, a business or a nation, then the greater the power you wield, the greater the responsibility to have to wield it ethically, and sometimes that means choosing not to wield it at all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships