Why your new year's resolution needs military ethics

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 13 AUG 2018

Weight loss goals and the laws of armed conflict seem pretty far removed. But stick with us! Military ethics provide useful principles to test the worth of our new year’s resolutions.

The ethics of war are based on making sure the inevitable harm, pain and suffering caused by violence is minimised as much as possible. Most resolutions also involve some pain and suffering. After all, we don’t need resolve to do what’s easy! So let’s apply these principles of warfare to the hardships of our resolutions and check if they’re are morally justified.

Just war theory, the most common approach to the ethics of war, says war is justified only if it satisfies a set of conditions. These include:

Just cause

War is only just when it is fought in response to a serious violation of state or human rights (basically, because war causes death and destruction it has to be responding to a grievous offence).

Right intention

The declaration of war is not motivated by private, self-interested or vicious intentions but out of a desire to bring about a just outcome.

Legitimate authority

Only the leader or leaders of a political community have the right to declare war.

(Macro) proportionality

The peace the war aims to create has to be preferable to the way the world would be if no war was fought (a nuclear war will almost always be disproportionate).

Last resort

Are there less harmful measures than war which might bring about peace?

Probability of success

Do not undertake the pain and suffering of war if there is no chance of winning, otherwise lives are wasted in vain.

(Micro) proportionality

The benefits gained from a military operation must outweigh the harms it inflicts.

Discrimination

Only combatants may be targeted by military attacks. Civilians are off limits.

Good goal

An ethical resolution will aim to achieve something good (health, travel, education). Don’t aim to do something you know to be bad (“This year I resolve to make profits at any cost”).

Right intention

Is your resolution motivated by a genuine desire for self-improvement? Or is it motivated by shame, peer pressure, greed, vanity or fear? If the latter is true, it might be worth considering whether it’s really a resolution worth making.

Is your resolution motivated by a genuine desire for self-improvement? Or is it motivated by shame, peer pressure, greed, vanity or fear?

Accept your limits

You only have the ‘authority’ to make resolutions for things within your control. Don’t resolve to get a promotion at work. Instead, resolve to reinvigorate your attitude at work so your application for promotion has the best chance of success. But remember, getting the promotion is outside your control.

Holistic improvement

Make sure you will be a better person overall after succeeding in your resolution. You might be able to run a marathon, but make sure it isn’t so detrimental to your health, relationships, work or other interests that you’re worse-off overall.

Avoid drastic measures

Have you tried less intense measures to achieve your goals? Maybe before you sign up for a 10 day silent yoga retreat you could try signing up for a weekly class and see if it helps.

Probability of success

Set realistic goals you can actually achieve. If you and your partner aim to spend more time together after three date nights in the last year, resolving to have a weekend away once a fortnight might be a bit extreme. Be honest to avoid setting yourself up for failure and making the effort and sacrifices you make futile.

Cost/benefit analysis

Is the inconvenience, expense or pain of your resolution worth it for the goal you are trying to achieve? Trying to have a body like Chris Hemsworth might be more trouble than it’s worth.

Own your resolution

Your resolution is your resolution – everyone except you is an innocent bystander! If you’ve decided to go vegetarian, that’s fine. Insisting everyone in your share house skips on meat to suit your new diet isn’t.

So there you have it – your guide to an ethical new year’s resolution with help from military ethics. These steps won’t guarantee your resolution is successful but they will guarantee it’s a resolution worth making. For tips on how to form the resolve, perseverance and courage it takes to stick to your new commitment, you might want to talk to a soldier.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

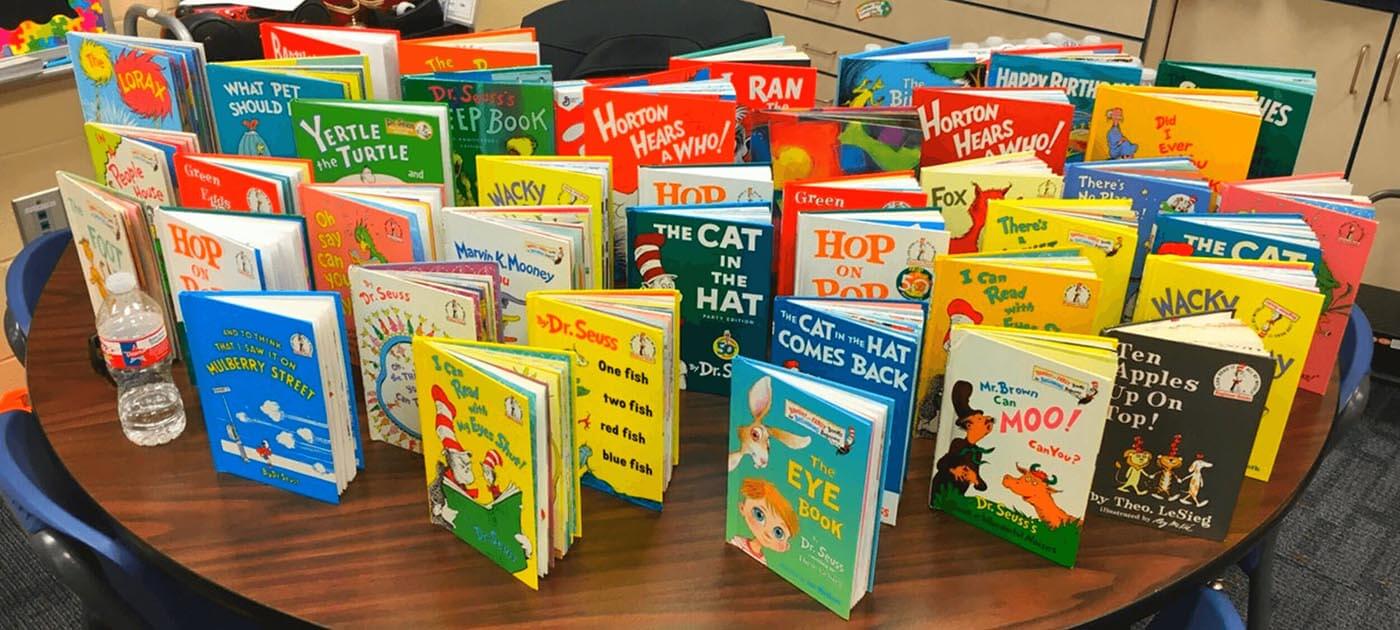

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Social media is a moral trap

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

This tool will help you make good decisions

This tool will help you make good decisions

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance 13 AUG 2018

The Ethics Centre has developed an online Quality Decision Making tool, due to be launched to Ethics Alliance members by the end of this year, to guide and support quality decision making for any member of an organisation.

Co-head of advice and education, John Neil, explains how the tool will help you in your business:

1. What is the Quality Decision Making tool?

The online platform guides users through a framework for ethical decision making, especially when those decisions are challenging and difficult. It provides personal insight, knowledge, awareness, case studies, tips, and hacks.

Ethics Alliance members are invited to be part of the testing and refining of the platform before its full roll out in November. Funded by The Ethics Centre, it has been custom designed for our corporate Alliance members and will be made available to all employees of Alliance members.

2. What kind of decisions can the tool tackle?

The platform is designed for difficult decisions – personal or professional – where there is no clear right or wrong answer. It will help discern:

• What is important

• What is at stake

• What matters most

• Who is involved

• Impacts and implications

• Possible options

• How to evaluate options

• What principles might apply to assess options

While helping solve a specific dilemma, the platform helps users develop core decision making capabilities, such as intention, context mapping, judgement, bias minimisation, root cause analysis, innovation, communication, wisdom, and courage.

3. What is the process like?

It takes about 45 minutes for first time users and, after that, return users will spend around 10 to 20 minutes on specific decision making challenges.

4. What is unique about this platform?

There are a number of decision making tools on the market, ranging from apps to analogue models, however the Quality Decision Making Platform is the first of its kind to combine skills development with help to make specific decisions.

5. Can you give me a scenario where it would help?

Troublesome rainmaker: You are a line manager in the finance sector. One of your key staff is excellent at her job and generates a lot of income for the company – no other team member comes close to her results. She has rejected overtures from competitor companies, much to your relief because your department is heavily reliant upon her abilities and your bonuses depend on your department’s profitability. Unfortunately, she has also been reported to HR and you about repeated inappropriate behaviour. What should you do?

Disaster warning: You work for the director of human resources and have access to confidential information about a coming restructure, including the names of those about to be made redundant.

At lunch, a colleague mentions her boss is about to take on a heavy debt to buy a new house, in preparation for the birth of his third child. You know that man is about to be made redundant. What should you do?

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Activist CEO’s. Is it any of your business?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Following a year of scandals, what’s the future for boards?

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

Banks now have an incentive to change

Banks now have an incentive to change

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance 13 AUG 2018

Pay for performance has earned itself a nasty reputation. During shocking revelations from the Hayne Royal Commission, bonuses and commissions linked to sales volumes have been blamed for driving all sorts of unethical and criminal behaviour.

To meet targets and get their bonuses and commissions, employees have charged fees for no service, inappropriately opened bank accounts for children, accepted bribes to approve mortgages, forged signatures, and sold people into loans and investments they could not afford.

All this was foreseeable. The conflicts of interest in tying financial rewards to sales targets have been well researched and documented over the past 50 years.

Yet, corporate leaders chose to stick with a system that rewards people for the volume they sell – sometimes even prioritising the riskier and more profitable investments – rather than the quality of the service they offer.

During the Royal Commission hearings, some banks pledged to remove “conflicted commissions” for their financial planners and restructure incentives for other staff, such as call centre workers. However, they have not always been receptive to the news that their rewards programs may be driving unethical behaviours.

Shaun McCarthy is an authority on organisational culture and chair of consultancy Human Synergistics. He says banks have given him short shrift in the past when he has warned about the conflicts of interest inherent in their incentive programs.

“I can talk to them until I am blue in the face about the unintended consequences but, if revenue is going up and profit is going up, they are not interested”, he says.

“They basically tell me to bugger off because they think their current success is a consequence of [their structures and processes]”, he says. “It is a misattribution of success.”

McCarthy says financial rewards for performance have a place in business, but they must balance with goals for customer service, feedback, repeat business, relationship management and other factors.

Human Synergistics’ research shows 32 variables influence organisational culture – and goalsetting comprises only four of them.

“They have to look at how people are managed through the entire system of the organisation to change the culture – not just get rid of the sales goals or whatever it might be”, says McCarthy.

“I have had banks tell me over the years that they need to have those aggressive cultures to compete in the marketplace, which means they simply do not understand the process – and they are learning it the hard way now”, he says, referring to the Banking Royal Commission.

Corporate leaders are often loath to change their incentive programs for fear star performers will leave and profits will suffer.

McCarthy urges them to hold their nerve. “The reward will be in the long term. You don’t necessarily have to get rid of the incentives, you don’t need to get rid of the goals, you just need to change what they are and how they are managed.”

Jon Williams has 30 years of experience helping businesses connect their people to their business results and has seen first-hand what can happen when individual rewards for performance are scrapped in favour of group rewards.

In his case, the result was an improvement in collaborative behaviour, without damage to business growth. Williams recently left professional services firm PwC, where he was global leader of people and organisation, to launch his consultancy, Fifth Frame.

A few years ago, when integrating two teams into one team of 20 executives, Williams decided to spread the bonus pool equally across all team members, regardless of individual performances.

“I knew that having them effectively compete for bonuses would drive behaviour counter to the aim of creating one new collaborating team.” – Jon Williams

Previously, only 30 percent of those executives – the highest performers – were offered bonuses, funded through the success of the business.

Under the new structure, the highest performers would earn a smaller bonus, while the remaining 70 percent of the team were awarded a share of the bonus pool for the first time.

The business performed well, providing an attractive bonus to all members. However, three months before the end of the financial year, one of the executives explained his results had not been strong, and it would be okay if he received no bonus that year.

“He was treating the relationship with the organisation and his team as a financial one”, says Williams, whose reply was, “No, you are in the team and you’ll get the same bonus as everyone else, and you need to be able look your colleagues in the eye and know you tried your best to deserve it’.”

“Instead of dropping off for the rest of the year, he redoubled his efforts”, says Williams.

“His team’s numbers didn’t actually get any better, but they threw his and their efforts into helping others who were busy and needed support.

“We had retained the incentives to make sure the team was paid fairly for their performance, but we had managed to maintain a social contract between the execs and each other and the company which resulted in better corporate behaviours and performance”, says Williams.

There are other motivations, apart from money, for doing good work, says Williams. Pride, ego, work ethic, long term aspirations, and competitive drive are some of them.

The vast majority of the Australian working population get themselves to work and perform their duties without being offered an extra incentive above their fixed salary.

Behavioural strategist Warren Kennaugh says employers need to accept that not everyone is motivated by money.

“Extrinsic motivators, such as money, aren’t as powerful as intrinsic motivators [such as pride].” – Warren Kennaugh

CEOs are often commercially oriented and believe that everyone else is too. “It is a problem that gets us into trouble because it sets simplistic behaviours”, says Kennaugh, who works with corporate leaders and elite athletes.

Using money as a reward can even make an enjoyable job feel like a chore, according to a meta-analysis of 128 controlled experiments by US Psychology professor Edward Deci and colleagues.

For every increase in reward, intrinsic motivation for interesting tasks declines by 25 percent and, when subjects know in advance how much extra money they will receive, intrinsic motivation decreases by 36 percent. (There is an argument that monetary rewards can increase motivation for boring tasks.)

“[Financial incentives] reduced creativity, diminished results, foster bad behaviour, inhibit good behaviour, and cost the business more to maintain,” says Kennaugh.

McCarthy says a badly structured incentives program will set employees against each other into a competition for the “prize money”.

“Because the message they take away from that [structure] is that it is not so much how you perform, but how you compare that counts.

“So now, people are focused on a competition, which requires people to win and lose.” You achieve the goal to win and create losers by not sharing information with them, he says.

Kennaugh says efforts to restructure incentive programs have to meet the “fairness test”.

A 2012 global study by PwC and the London School of Economics and Political Science finds “… executives are content as long as they are paid what they consider to be ‘fair’ within the hierarchy of their own company, and comparably against those on a similar level in competitor companies, to the extent that it almost becomes irrelevant how much they are paid”.

Employees will punish employers if they feel short changed, says Kennaugh.

“When it is review or bonus time, I am reflecting on every Sunday night that I left home to fly somewhere, every birthday party I didn’t get to, every State of Origin game I didn’t get to see and I’m not sure I have got a figure, but I have an emotional amount that, in my mind, that is what it has all been worth.

“The moment that I am not [paid fairly], I will go on some form of private strike”, he says. “And the dilemma of organisations is that they don’t own the fairness test.”

When the New Jersey police force won less than officers wanted in salary negotiations, arrest rates and average sentence length declined – indicating that police were putting in less discretionary effort.

“For a period of about 18 months after collective bargaining, the cops went on strike”, says Kennaugh.

This is a warning that employers must tread carefully when restructuring their financial incentive programs – especially when some people will be disadvantaged by those changes.

Employers should try to implement the changes in stages and think about how to deal with the fallout.

“I’d be concerned about the implications about how people are likely to manage it and retaliate. If I’ve been getting it and [I feel] it is an earned right, what are you going to give me to compensate?”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Feel the burn: AustralianSuper CEO applies a blowtorch to encourage progress

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Capitalism is global, but is it ethical?

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

The Royal Commission has forced us to ask, what is business good for?

The Royal Commission has forced us to ask, what is business good for?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance The Ethics Centre 13 AUG 2018

AMP Capital was applauded last year when it committed to selling $600 million worth of shares that did not meet its ethical guidelines. However, barely a year after announcing it was getting rid of its direct and indirect interests in tobacco and landmines, AMP was itself ejected into a basket of “untouchables”.

Australian Ethical announced in May it was divesting itself of AMP shares in the wake of searing revelations from the Financial Services Royal Commission.

Billions of dollars were wiped from the value of AMP after the public and investors discovered the wealth manager charged “fees for no service” and steered people into investments that rewarded their financial planners, at the expense of the clients.

Head of ethics research at Australian Ethical, Dr Stuart Palmer, says there were a number of reasons behind the decision to divest, “… but specifically, a senior decision made within the financial planning business to charge clients fees for services they weren’t receiving. They knew it was wrong, they knew it was illegal.

“There were people in the business saying we need to stop doing this, and they kept doing it at a senior level”, he says.

The Royal Commission into Financial Services has been exposing the rot eating away at some of our biggest and most powerful corporations and has reenergised an ongoing debate about what is the actual purpose of business and who it serves.

Palmer says legal cases in the US established shareholder primacy a century ago, with the primary responsibility of business interpreted as creating profits for shareholders.

“Since then, and before then, there has been a debate about whether that is right, whether there are other ways of thinking about corporations having independent interests and responsibilities to all their stakeholders, including shareholders, but also employees, customers, suppliers and society”, says Palmer.

“None is necessarily dominant over the others, but they need to be balanced in the interests of all.”

This discussion about the role of the corporation is being weighed up at all levels, including by the chairman of NAB, Ken Henry, who delivered a speech in March saying that it was not enough for companies to use the “pursuit of profit” to explain away their contribution to negative consequences, such as greenhouse gas emissions and other forms of pollution.

“If that’s the best we can do, then we shouldn’t wonder that we find it so difficult to occupy positions of trust and respect in society. Neither should we wonder that politicians of all political colours have such an uneasy relationship with us”, he told a gathering of the Australian Institute of Company Directors.

This was a debate that the Commonwealth Bank non-executive director, Harrison Young, was alluding to when he wrote last year, “banks should not be profit-maximising institutions. They have duties to the community that oblige them to forego a certain amount of upside”.

Judith Fox, the CEO of the Australian Shareholders Association, says she is aware of increasing numbers of companies and boards having this discussion.

“I’m seeing a lot of conversations that ultimately are all about how something needs to change in the way we operate”, she says.

“I think we are one of those transition periods where there has been a social norm that the purpose of a company is shareholder return and that has been accepted in markets worldwide for four decades”, she says, adding the realisation that companies should stand for more than just profits may come as a surprise to people whose knowledge of economics does not extend further back than US economist Milton Friedman’s pronouncement in 1962 that there is only one social responsibility of business and that is to make money.

Friedman wrote in Capitalism and Freedom:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

Fox says the current debate about the role of the corporation is a return to the concept, popular in the 1930s – that business had a social role to play as well.

Professor of Human Rights Law at Sydney University, David Kinley, agrees that many people’s attitudes are formed by what they have experienced in the past 20 years.

“It is what they have seen since the 80s, which has been a long – until 2008 [the start of the Global Financial crisis] – largely uninterrupted boom period.”

Kinley says Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith would be horrified to see the societal cost of rampant free marketeers.

Smith had written in The Wealth of Nations, nearly 250 years ago:

“… that individual acts of economic self-interest combine, through the ‘invisible hand’ of market forces, to further the best interests of society at large”.

Says Kinley, “So, he certainly would be turning in his grave to see all this wealth, so much of it is now concentrated in the hands of the few. Yes, we are better off than we were 200 years ago. Unquestionably. But by God, it’s been at a big cost to the notions of equity and fairness.

“And [investor] Warren Buffett says often – and he is the second richest man in the world – he said he is amazed there are not more people with pitchforks heading for the rich like him because he can’t see how they don’t appreciate this appalling inequality.”

Kinley, author of Necessary Evil: How to Fix Finance by Saving Human Rights, says he is not advocating some sort of Socialist revolution, but remaking the “financial, commercial, corporate neoliberal system that we now have one that works better for people as a whole”.

“If you don’t do that, you have a bubbling up of disquiet, of resentment, that no matter what happens – even things like the global financial crisis – the rich, the powerful, the banking, the financial system, they sail through it, on the back of public funds that bailed them out because they had to be saved. When people ordinary people look at that, they say, ‘How is that fair?’.

“So you get the reaction of, ‘Well, let’s vote in somebody who is willing to drain the swamp, you know, shake up the area and I don’t care if he’s mad or narcissistic or a nincompoop. You put him in there in the White House and just see what happens.’

“These sorts of reactions are almost desperation. I don’t think they are logical, I don’t think they are at all laudable, but you see why people are doing it.”

While there is evidence ethical investments outperform the average large-cap Australian share funds over three, five and 10 year time horizons, Kinley maintains corporations and their executives should be ethical because it is the right thing to do, not because it might make them money.

“What I would suggest what all of us want to do in the morning, truly, is to stand in front of the mirror as you’re brushing your teeth and say, ‘I’m proud of what I do or at least I can see why I do what I do and it is something that is worthwhile’.

“You don’t want to look in the mirror and think, ‘Oh I’m making a lot of dosh, but Geez it is dodgy’.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

LISTEN

Business + Leadership

Leading With Purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership