Schools of thought: What is education for?

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Georgia Fagan 3 OCT 2024

Education is often seen as an economic investment in our future. But philosophers have argued it could be so much more than this.

Education is often seen as a tool that we use to get us other things that we want; we tend to value education instrumentally. We know that the higher our educational attainment, the higher our future income, and most of us see this increase in future economic value as one of the central values of education. We understandably see greater financial security as a means to achieve greater happiness, a way to avoid stress and enjoy a greater sense of freedom and agency in our lives.

But what else could education be for that it seemingly isn’t for at the moment? What other value could it have for ourselves and the communities in which we are embedded?

Many people believe that economic instrumentality shouldn’t overshadow other potential goals of education. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes:

“We are living in a world that is dominated by the profit motive. The profit motive suggests to most concerned politicians that science and technology are of crucial importance for the future health of their nations… my concern is that other abilities, equally crucial, are at risk of getting lost in the competitive flurry, abilities crucial to the health of any democracy internally and to the creation of a decent world culture.”

Nussbaum is concerned that a failure to sufficiently interrogate what systems of education should be used for, leaves those systems vulnerable to a corporatisation that neglects their more comprehensive capacities.

Social critic Henry Giroux echoes these concerns, saying:

“You can’t have a democracy without informed citizens. That’s why education has to be at the centre of any discourse about democracy, and it isn’t. That’s where the left has failed. It has failed to run education. They failed because they believe that the most important structures of domination are entirely economic…”.

In 2027 the NSW primary school curriculum will undergo its biggest change in 30 years. Amongst this will be a new focus on democratic roles and the history of voting. Teaching students about democratic systems is useful, but it’s not enough. We must also teach them to interrogate their own beliefs and deliberate with others whose beliefs differ from their own. This is a skill which Nussbaum calls Socratic self-criticism. She describes it as “the ability to transcend local loyalties and to approach world problems as a ‘citizen of the world’; and, finally, the ability to imagine sympathetically the predicament of another person”.

For Nussbaum (and Socrates) education should aim to create citizens who are skilled in thinking for themselves, in reasoning well alone and with others. Similarly, Giroux thinks education should make individuals “aware of their own cultural capital… and their place in the world”. Nussbaum and Giroux both argue that education should not only give students what they need to lead economically comfortable lives, but also ensure that these lives are self-aware, and meaningfully engaged with the world around them.

Both theorists begin to suggest ways in which their theories can be made into practice. Giroux emphasises the need to engage students in discussions and forms of thinking that allow them to consider their own narratives about the world. This requires understanding the ways in which they are situated within it, and how that situatedness may differ from those around them.

This idea echoes Nussbaum’s argument that education should teach students to think critically about their own traditions. Both these proposals require curriculums that directly consider the perspectives of other people and cultures to stimulate critical self-reflection. Questions like: “what do I believe in and what are my reasons for those beliefs?”, “what do I think of the alternative beliefs?”, and finally, “do I or do I not want to change my thinking in this instance?”.

The development of aspects of Socratic self-criticism already exists as a byproduct of education curriculums, but Nussbaum and Giroux are motivating us to consider what it would look like to bring these aims to the centre of schooling. An example may be through the inclusion of a core subject concerning ethical deliberation. The best preliminary example of this sort of subject may be the Primary Ethics subject model. Currently, this is an hour long, weekly class carried out as an opt-in secular alternative to special religious education in NSW primary and secondary schools.

Any such subjects should not be forged as tools to impart ethical dogmas onto young students. Instead, they should be spaces for developing critical thinking skills which arise from debate and deliberation with existing perspectives and counter perspectives.

Education is a hugely powerful system, one which we should thoroughly and frequently interrogate. Are we using this system in a way that aligns with our goals, both local and global? What are those goals, have they recently changed? Are we equipping an entire generation with the tools they require to live comprehensively fulfilling and meaningful lives? The possibilities for our educational systems are boundless and it’s time that we begin realising this.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

While the stories of Virginia Woolf are not traditionally considered as works of philosophy, her literature has a lot to teach us about self-identity, transformation, and our relationship to others.

“A million candles burnt in him without his being at the trouble of lighting a single one.” – Virginia Woolf, Orlando

Woolf was not a philosopher. She was not trained as such, nor did she assign the title to herself, and she did not produce work which follows traditional philosophical construction. However, her writing nonetheless stands as comprehensive, albeit unique, work of philosophy.

Woolf’s books, such as Orlando, The Waves, and Mrs Dalloway, are philosophical inquiries into ideas of the limits of the self and our capacity for transformation. At some point we all may feel a bit trapped in our own lives, worrying that we are not capable of making the changes needed to break free from routine, which in time has turned mundane.

Woolf’s characters and stories suggest that our own identities are endlessly transforming, whether we will them to or not.

More classical philosophers, like David Hume, explore similar questions in a more forthright manner. Also reflecting on matters of the stability of personal identity, Hume writes in his A Treatise of Human Nature:

“Our eyes cannot turn in their sockets without varying our perceptions. Our thought is still more variable than our sight; and all our other senses and faculties contribute to this change; nor is there any single power of the soul, which remains unalterably the same, perhaps for one moment. The mind is a kind of theatre…”

Woolf’s books make similar arguments. Rather than stating them in these explicit forms, she presents us with characters who depict the experience that Hume describes. Woolf’s surrealist story, Orlando, follows the long life of a man who one day awakens to find themselves a woman. Throughout we are made privy to the way the world and Orlando’s own mind alters as a result:

“Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than to merely keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.”

When Hume describes the mind as a theatre, he suggests there is no core part of ourselves that remains untouched by the inevitability of layered experience. We may be moved to change our fashion sense and, as a result, see the world treat us differently in response to this change. In turn, we are transformed, either knowingly or unknowingly, by whatever this new treatment may be.

Hume suggests that, while just as many different acts take place on a single stage, our personal identities also ebb and flow depending on whatever performance may be put before us at any given time. After all, the world does not merely pass us by; it speaks to us, and we remain entangled in conversation.

While Hume constructs this argument in a largely classical philosophical form, Woolf explores similar themes in her works through more experimental ways:

“A million candles burnt in him”, she writes in Orlando, “without his being at the trouble of lighting a single one.”

Using the gender transforming character of Orlando, Woolf examines identity, its multiplicity, and how, despite its being an embodied sensation, our sense of self both wavers and feels largely out of our control. In the novel, any complexities in Orlando’s change of gender are overshadowed by the multitude of other complexities in the many transformations that one embarks in life.

Throughout the book, readers are also given the opportunity to reflect on their own conceptions of self-identity. Do they also feel this ever-changing myriad of passions and selves within them? The character of Orlando allows readers to consider whether they also feel as though the world oftentimes presents itself unbidden, with force, shuffling the contents of their hearts and minds again and again. While Hume’s Treatise aims to convince us that who we are is constantly subject to change, Orlando gives readers the chance to spend time with a character actively embroiled in these changes.

A Room of One’s Own presents a collated series of Woolf’s essays which explore the topics of women and fiction. Though non-fictional, and evidently a work of critical theory, Woolf meditates on her own experience of acquiring a large, lifetime inheritance. She reflects on the ways in which her assured income not only materially transformed her capacities to pursue creative writing, but also how it radically transformed her perceptions of the individuals and social structures surrounding her:

“No force in the world can take from me my [monthly] five hundred pounds. Food, house and clothing are mine for ever. Therefore not merely do effort and labour cease, but also hatred and bitterness. I need not hate any man; he cannot hurt me. I need not flatter any man; he has nothing to give me. So imperceptibly I found myself adopting a new attitude towards the other half of the human race. It was absurd to blame any class or any sex, as a whole. Great bodies of people are never responsible for what they do. They are driven by instincts which are not within their control. They too, the patriarchs, the professors, had endless difficulties, terrible drawbacks to contend with.”

While Hume tells us, quite explicitly, about the fluidity of the self and of the mind’s susceptibility to its perceptual encounters, Woolf presents her readers with a personal instance of this very phenomenon. The acquisition of a stable income meant her thoughts about her world shifted. Woolf’s material security afforded her the freedom to choose how she interacts with those around her. Free from dependence, hatred and bitterness no longer preoccupied her mind, leaving space for empathy and understanding. The social world, which remained largely unchanged, began telling her a different story. With another candle lit, and the theatre of her mind changed, the perception of the world before her was also transformed, as was she.

If a philosopher is an individual who provokes their audiences to think in new ways, who poses both questions and ways in which those questions may be responded to, we can begin to see the philosophy of Virginia Woolf. Woolf’s personal philosophical style is one that does not set itself up for a battle of agreement or disagreement. Instead, it contemplates ideas in theatrical, enlivened forms which are seemingly more preoccupied with understanding and exploration rather than mere agreement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Hope

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 21 MAR 2023

Parental leave policies are designed to support and protect working parents. However, we need to exercise greater imagination when it comes to the roles of women, family and care if we are to promote greater social equity.

In October 2022, prime minister Anthony Albanese announced a major reform to Australia’s paid parental leave scheme, making it more flexible for parents and extending the period that it covers. Labor’s reforms are undoubtedly an improvement over the existing scheme, which has been insufficient to address gender-based disadvantage.

Labor’s new arrangement builds on the current Parental Leave Pay (PLP) scheme. This entitles a primary carer – usually the mother – to 18 weeks paid leave at the national minimum wage, along with any parental leave offered by their employer. It runs in parallel to the Dad and Partner Pay scheme, which offers “eligible working dads and partners” two weeks paid leave at the minimum wage. Recipients of this scheme are required to be employed and recipients of both need to be earning less than ~$156,000 annually.

Albanese’s announced expansion of the PLP will increase it to 26 weeks paid leave by 2026, which can be shared between carers if they wish. Labor claims that this will offer parents greater flexibility while retaining continuity with the existing scheme.

Labor’s new scheme is an improvement over the older arrangement, but is it enough to move society closer to the goal of social equity? To do so, we need to do more to reduce the marginalisation of women economically, in the home and in the workplace, and to expand our imagination when it comes to parenthood and caring responsibilities.

Uneven playing field

Gender-based disadvantage is a global occurrence. Currently, being a woman acts as a reliable determining factor of that person’s social, health and economic disadvantage throughout their life. Paid parental schemes are one type of governmental policy that can facilitate and encourage the structural reform necessary to address gender-based disadvantage. Certain parental leave policies can help reconfigure conceptions about parenting, family and work in ways that better align with a country’s goals and attitudes surrounding both gender equity and economic participation.

Paid parental leave schemes that provide adequate leave periods, pay rates, and encourage shared caring patterns across households, can fundamentally impact the degree to which one’s gender acts a significant determining factor of their opportunities and wellbeing across their lifetime.

The Parenthood, an Australian not-for-profit, emphasises that motherhood acts as a penalty against women, children and their families. This penalty is experienced acutely by women who have children and manifests as diminished health and economic security, reducing women’s social capacity to achieve shared gender equity goals. Their research highlights that countries that offer higher levels of maternity and paternity leave, such as Germany, in combination with access to affordable childcare results in higher lifetime earnings and work participation rates for women.

Australia’s existing PLP scheme, on the other hand, works to both create and foster conditions that reduce the capacity for women to achieve the same social and economic security as their male peers. It hugely limits women’s capacity to return to work, to remain at home, and to freely negotiate alternative patterns of care with their partners. This in combination with a growing casualised workforce who remain unable to access adequate employer support emphasises the need for extensive policy amendments if we hope to realise our goals of social equity.

Labour’s proposed expansion incrementally begins to better align the PLP with the goals set forth by organisations like The Parenthood.

Providing women and their families with more freedom to independently determine their work and social structures may mark the beginning of a positive move against gender-based disadvantage. However, the proposed expansion is not a cure-all for a society that remains wedded to particular conceptions of women, parenting, and labour more broadly.

The working rights of mothers

We can see how disadvantage goes beyond parental leave by looking at how mothers are treated in workplaces such as universities. Dr Talia Morag at the University of Wollongong advocates for the working rights of mothers employed within her university. Prior to Albanese’s announcement, Morag emphasised the cultural resistance, or rather a lack of imagination, when it came to merging the concept of motherhood with an academic career.

Class scheduling, travel funding and networking capacities are all important features of an academic career that require attention and reconfiguration if mothers, especially of infants and young children, are to be sufficiently included and afforded equal capacities to succeed in university settings.

Even under expanded PLP schemes, mothers who breastfeed, for example, face difficulty when returning to work if they remain unsupported and marginalised in those workplaces. As Morag emphasises, many casual or early-career academic staff are unentitled to receive government PLP or university funded parental leave.

Critically, the associations between being woman and being taken to be an impediment to one’s workplace is not an issue faced solely by those who become mothers.

As Morag remarks, “it does not matter if you are or are not going to be a mother, you will be labelled as a potential mother for most of your career. And that will come with expectations and discrimination.”

The gender-based disadvantage emergent from these cultural associations will remain if broader cultural change is not sought alongside expanded PLP schemes.

Expanding our imaginations as to how current notions of motherhood, family and caring patterns can look will require the combined efforts of expanded PLP schemes and the creation of more hospitable working environments for parents. Women may remain being seen as potential mothers and potential liabilities to places of work, however this liability may slowly begin to shift.

We historically have, and seemingly remain, committed to reproducing our species. This means we continue to produce little people who grow up to experience pleasure, pain, and everything in between. If we also see ourselves as committed to managing some of that pain, to expanding the opportunities these little people get, as well as reducing how gender unfairly determines opportunity on their behalf, we will require policies that assist parents to do so.

Affording families this chance benefits not only mothers, or parents, but also their children, their children’s children, and all others in our communities. Granting parents the capacity to choose who works where and when can help us, incrementally, along a long path to a world that is perhaps more dynamic and equitable than we can even begin to envision.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Georgia Fagan 23 NOV 2022

Donald Trump has announced his second run for presidency in 2024. With a reputation for both passive and active violence, and a disregard for democratic integrity, the prospect of another Trump presidency is feared by many. But for others, his re-election would mark the promising return of a strong, capable leader. How do we begin to make sense of these contemporary communities which seem to either fear or revere their elected leaders? And are there ways such polarised receptions can ever be avoided?

Historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat knows just how Trump, operates. He’s following the strongman’s playbook, one that has four guiding features. Strongmen put their personalities at the front of their politics, they embrace machismo norms, relish in corruption, and do not shy away from the power of violence. We can use these insights to sniff out the strongmen lurking in systems of governance. Ben-Ghiat emphasises that we should be strongly motivated to do just this, as there is ‘too much at risk not to try’.

Cultish personalities are formed around these political leaders as they work to present themselves as ‘a man of the people’. They emphasise their standout character while simultaneously asserting themselves to be no different than the common citizen.

Their embracing of machismo, Ben-Ghiat explains, is reflected in hypermasculine behaviours, showcasing these examples with shirtless photos of both Trump and Putin. Women, they say, are ‘the enemy of the strongman’.

Corruption in the case of the strongman is of both the ‘moral and professional’ variety. We are told that the strongman commonly grants pardons which ‘free up criminals for service’, channelling those who some may take to be immoral offenders into positions of political power.

To convey their relationship to violence, Ben-Ghiat directs us to the presence of weapons in recent Republican political campaigns in the United States, telling us that these men ‘think they look strong, but it is really a sign of insecurity’. The strongman is making up for something.

Ben-Ghiat tell us that a contemporary commonality of these men is that they are often democratically elected, and that they pose considerable threats to the democratic systems in which they embed themselves.

Trump’s rallying tactics and his subsequent role in and commentary on the 2021 Capitol riot may be taken as emblematic of these strongman features. His mass appeal has been argued as being largely derived from ‘performative’ techniques that obfuscate his political goals or capacities more broadly. Trump continues to claim the democratic integrity of the United States to be under threat, asserting the actions of the Capitol rioters as warranted given the presence of electoral fraud in the country.

In these ways and others Trump seems to aptly align with Ben-Ghiat’s constructed, strongman persona. Impeachment, ongoing congressional hearings and public scrutiny evidently do little to undermine Trump’s confidence and his desire to reobtain the political power he once held.

There are mounting concerns that this phenomenon is not isolated to the United States. And that politicians globally can be seen as working to strengthen centralised systems of political power in ways which align with authoritarian leadership regimes. Could there be a risk that even the most historically democratic governments could begin to shift in comparable ways? If so, what could be done to manage that risk?

–

Pursuing political instigators of harm is a coherent goal and a strong incentive to Ben-Ghiat’s work. State leaders, even when democratically elected, are fashioned with powers that endow them the capacity to do both a world of good, and a world of harm. Many people were directly harmed by policies of the Trump administration; even more were harmed from the uncertainty his particular presence in office brought into their daily lives.

Ben-Ghiat recognises these sorts of harms and aims to call out the various features which they take as both forging and propagating them, egotistical, corruptive, and violent figureheads. When bundled together, these form the strongman, and for Ben-Ghiat the strongman should be our target.

If the goals of this work are the management of uncertainty and the desire to retain confidence in our capacity to uphold democratic structures and installed systems of justice, and we are sympathetic to these goals, we need ask what Ben-Ghiat’s approach to achieving them misses, or more poignantly, what it risks.

Bertrand Russel, not unlike Ben-Ghiat, was similarly sceptical of politicians. He remarks, “since politicians are divided into rival groups, they aim at similarly dividing the nation…”. Importantly distinct from Ben-Ghiat however, Russel’s scepticism is namely directed at the two-party political system as it stood in early 20th century Britain, and the impact this system has on the wider populations who comprise it.

Features of Ben-Ghiat’s strongman criteria are not in opposition to Russel’s characterisation of political figures more broadly. Yet Russel’s evaluations of these harm attend more heavily to the relationships that citizens, or voters, have to these politicians.

“The power of the politician, in a democracy” Russel writes, “depends upon his adopting the opinions which seem right to the average man”. For Russel, both the best and the worst of our politicians are reflections of and responsive to the ideas and sentiments of the populations they operate within.

The risk of Ben-Ghiat’s approach is that attending so heavily to the strongman, determining what he is and is not, may unhelpfully be turning our gaze away from our communities who, as Ben-Ghiat remarks, oftentimes democratically elect the very figureheads they and others wish to repudiate.

Sources of harm do not always come to us wrapped up in neat and tidy (shirtless) packages. Tirelessly seeking to group together ‘bad men’ can diminish our capacity to see other less precise but perhaps more pervasive sources of harm.

Comprehensively managing any risk a strongman may pose to our society will only be minimally addressed by stringing together various features that are said to necessarily render that man strong.

There is certainly time and space for the sort of work Ben-Ghiat dedicates themselves to.

Though if we are committed to protecting systems of democracy, and to ensuring that basic rights are genuinely upheld, we may be best served by turning our attention away from contemporary figureheads and towards those who cast their votes in favour of them, and to those systems of governance that forge and foster polarisation.

Naming and shaming the strongman, however accurately, will do little in the face of many who take his central features to be admirable strengths. Let us ensure that our pursuits of certainty and stability do not come at the cost of neglecting to engage with those around us who evidently have different assessments about just how risky a strongman really is.

Tune into Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s full FODI 2022 discussion, Return of the Strongman

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Hear no evil’ – how typical corporate communication leaves out the ethics

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Georgia Fagan 17 MAR 2022

Assessed from a distance, Australia’s healthcare system may seem to shine.

Contrasted with the near non-existence of subsidised medicine in the United States, and the increasing shortages of doctors and other specialists seen globally, Australia could be taken as providing healthcare at least a calibre above the rest. However, with a closer look, it quickly becomes apparent that one’s assessment of the ethical status of Australia’s healthcare system is one that is decidedly dependent upon the vantage point of the assessor.

When we narrow our scope and focus instead on the internal workings of the Australian system, holding it to a local, desired standard of performance, its ethical misgivings readily become apparent. If the role of a successful healthcare system is to provide equally for all, where illness, disability or socioeconomic status do not stand as features which reliably disenfranchise its users, then the current formation of our local system does not seem to ethically sparkle.

Dr Annmaree Watharow was a general practitioner for over two decades. She is a recent PhD graduate from the University of Technology Sydney where she completed her dissertation on the healthcare and hospital experiences of those who have dual sensory impairments. She has published works on topics ranging from improving communication within healthcare environments to fostering improved practice in research settings, along with personal testimonies on her experiences of living with deafblindness.

When I ask Dr Watharow what she takes to be the central ethical failure of our current healthcare system, she responds concisely:

“Parity of access to quality healthcare is the key ethical issue.”

If we agree that equal access is a central pillar to an ethical system of healthcare, we are required to understand who is currently being left out and why, in order to begin remedial work.

“Migrant populations, homeless, incarcerated, LGBTQI+, veterans, older Australians, Indigenous Australians, and people living with disability and chronic illness” are all social groups that Dr Watharow sees as belonging on the (not exhaustive) list of those who are directly and negatively impacted by the apparent partialities in contemporary healthcare systems.

Where there are losers, there are also winners – or, at the very least, those who remain comfortable in the current modes of national healthcare dissemination. When considering the broader Australian population, Dr Watharow suggests, “Multiple sections are disadvantaged, but you have a core group who are well positioned to leverage advantage. These are people with good income, good housing, good nutrition”.

Pre-existing social structures that both create and sustain sharp disparities in income, quality of housing, education and health work to negatively impact an individual’s wellbeing. These factors are oftentimes discussed as being ‘social determinants of health’, such that they directly affect a person’s risk of developing physical or mental illness. Dr Watharow importantly draws our attention to how those belonging to disenfranchised groups are subsequently more likely to be negatively impacted by facets of our social structure that reach far beyond the healthcare system.

“There are inadequacies in our social welfare, justice and recognition systems which fail these groups”, Dr Watharow explains. When considering current pensions and welfare allowances for example, it is apparent that some individuals have their health compromised long before they end up in a hospital bed. “The current funds don’t allow people to practice healthcare or good nutrition or have quality housing. All of these contribute to poorer healthcare outcomes.”

Evidently, assessments of the ethics of our healthcare system would be incomplete without an assessment of the broader society in which that system operates. Dr Watharow helpfully turns our focus to how broader, socioeconomic disadvantage necessarily breeds unequal access to and benefit from current systems of healthcare.

Better understanding these causal factors, which directly contribute to this inequality, usefully directs us towards finding pragmatic solutions, and Dr Watharow is clear in pointing out a pivotal step that is necessary to spur positive change: we need to provide a means by which the wide array of disenfranchised voices may articulate the intricacies of their own disadvantage.

“The lynchpin of the medical system should be shared decision making. For that to happen, everyone needs access, they need communication, and communication support if not able to communicate.” Ensuring the representation of marginalised voices in both research and political settings is a necessary step towards the shared decision making required for the construction of an ethical, inclusive healthcare system. If particular users of the healthcare system are silenced in their capacity to communicate their needs or experiences, inequality will be fostered.

Critically, creating the capacity for individuals to speak truth to the power is only the first step. “We need an attitudinal shift in how we treat those who are older, have a disability, or cognitive impairment. We need healthcare institutes to comply with the statues that exist on an international, national, and state levels that prohibit abuse, neglect, and violence, as well as promote healthcare.”

Dr Watharow emphasises that Australians, especially Indigenous Australians, living with disability are a key population who remain poignantly disadvantaged in the current healthcare system. Even with the construction of government services such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), these groups continue to suffer in the face of discriminatory social systems which stifle the capacity for their needs to be adequately heard across community, research, and political settings.

“I think the NDIS [National Disability Insurance Scheme] has severely short-changed First Nations peoples by not understanding that their disability experiences and needs are not the same as non-Indigenous. Disability is understood differently and there are major barriers to getting disability services to rural and remote regions. Added to this, many First Peoples need basic things like shelter, food, work; if you haven’t got the money for a bus fare to town you can’t go get assessed, if you haven’t got predictable housing how do you get home help?”.

Recognising the insufficiencies of social welfare schemes and the impact these have on practices of healthcare again draws our attention to the importance of addressing nationwide, systemic inequality in order to construct ethical systems of healthcare. Unfortunately, aiming to remedy broader social inequalities as a method to achieve equitable healthcare may appear a slow and arduous approach. Luckily, as Dr Watharow suggests, these ambitions need not be pursued in lieu of more targeted action.

“If we put in some basic work to expecting our health environments to be compliant with universal design principles and disability standards; if we expect our staff there to be aware, knowledgeable and compliant with accessibility and communication provisions (which are enshrined in legal statutes) and if we enforce these with audits, spot checks and evaluation of complaints, if we make it a condition of service that staff do yearly training and upskilling in providing equitable access and communication and care to PLWD [people living with disabilities], we can do so much!”

The process of constructing an ethical healthcare system in Australia requires both remedial and aspirational work. Currently, quality healthcare cannot be equally accessed by all. Understanding which groups face obstacles to access, and why, is a critical starting point for resolution. We require a commitment to ensuring individuals can communicate their needs and critiques of current models, and that these calls are heard and responded to. Concurrently, it must be demanded that pre-existing standards of care are reliably upheld and not entirely disregarded.

Critically, neither of these methods will be pursued if current attitudes toward particular members of our society remain engrained. As Dr Watharow offers, “a greater inclusion and tolerance of difference in all levels of society” is required if we are to garner the motivation required to remedy existing inequalities.

The solutions are multifaceted, slow, and likely expensive. But if we are committed to equality, both in systems of health and in our societies more broadly, the gap between those who can enjoy healthy lives, and those who cannot, should slowly close.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The virtues of Christmas

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 17 JAN 2022

As it stands, the term “freedom” is being utilised as though it means the same thing across a variety of communities.

In the absence of a commitment to expand discourse between disagreeing parties, we may regrettably find ourselves occupying an increasingly polarised society, stricken with groups which take communication with one another as being a definitively hopeless exercise.

Freedom and its nuances have come poignantly into focus over the past two and a half years. Ongoing deliberation about pandemic rules and regulations have seen the notion being employed in myriad ways.

For some, freedom, and one’s right to it, has meant demanding that particular methods of curtailing viral spread remain optional and never be mandated. For others, the freedom to retain access to secure healthcare systems and avoid acquiring illness has meant calling for preventative methods to be enforced, heavily monitored, and in some cases made mandatory. Across most perspectives, individual freedoms are taken as having been directly impacted to degrees not previously experienced.

The concept of freedom, for better or worse, reliably takes centre stage in much political debate. The ways we conceive of it and deliberate on it impacts our evaluation of governmental action. It appears however that the term often comes into conflict with itself, forming what may be characterised as a linguistic impasse, where one usage of freedom is evidently incompatible with another.

Canonical political philosopher Hannah Arendt addresses the largely elusive (albeit valorised) term in her paper, ‘What is Freedom?’. In it, she emphasises its inherent confusion: “…it becomes as impossible to conceive of freedom or its opposite as it is to realize the notion of a square circle.” Despite the linguistic and conceptual red flags which freedom bears, Arendt, and many others, persist in grappling with the topic in their work.

I am also sympathetic to the commitment to ongoing deliberation on the matter of freedom. Devoting time to understanding visible impasses which arise in its usage appears vital. Doing so aids in encouraging productive discussions on matters of how states should act, and to what extent a populace should comply with political directives.

As these are discussions central to the maintenance and progression of liberal democratic societies, we should feel motivated to formulate responses in situations where one conception of freedom comes into conflict with another.

The seemingly inevitable inaccuracies embedded within the concept of freedom and the difficulties inherent in the project of discriminating between the emancipatory and the oppressive remains evident across recent political rhetoric and subsequent public response. From 2020, many politicians began using the term freedom to emphasise the need to make present sacrifice for future gain, and to secure safety for vulnerable populations by curtailing the spread of COVID-19. For some, this placed politicians in the camp of the emancipators, working to defend our freedom against a looming viral force. In contrast, those who opposed measures such as lockdowns took the relevant enforcers to be oppressors, acting in total opposition to a treasured freedom of movement and individuated determination.

Both those in favour of and those opposed to lockdowns were seen utilising the term freedom in the public arena, yet freedom to the former necessarily required a certain degree of political intervention, and freedom to the latter firmly required a sovereignty from political reach. This self-oriented sovereignty is one in which freedom is experienced not in our relation to others, but individualistically, through the deployment of free will and a safety from political non-interference. While these two differing utilisations of freedom are broad and not immutable, they do provide a useful starting point from which to assess contemporary impasses.

Commitment to sovereignty as necessary for a commitment to freedom is not a new position, nor is it reliably misplaced. The individual who decries re-introduced mask mandates, or vaccines being made compulsory in workplaces evidently takes these actions as being incompatible with the maintenance of freedom, and a free society more broadly. Their sovereignty from political interference is necessary for their freedom to persist.

Both historically and contemporarily, many have seen it essential to measure their own freedoms by the degree to which states did not unduly intervene upon realms of education, religion, or health. We know countless instances where political reach has chocked public freedoms to undesirable extents. Those in opposition to vaccine mandates, for example, may take freedom to begin wherever politics ends, thinking it best to safeguard their liberties with one hand while defending against political reach with the other.

In contrast, politicians and individuals who deem actions such as vaccine mandates, lockdowns, and the like as necessary for the maintenance of long-term social freedoms are seen as upholding a competing notion of freedom. For this group, politics and freedom are beyond compatible, they are deeply contingent upon one another. On this conception, emancipation from political reach would result in a breakdown of society, where inevitably some personal liberties would be infringed upon by others.

This position of the compatibility between freedom and politics is articulated and advocated for by Arendt. Arendt argues that sovereignty itself must be surrendered if a society is ever to be comprehensively free. This is because we do not occupy earth as individuals, but as communities, moreover, political communities, which have been formed and continue to be maintained due to the freedom of our wills. “If men wish to be free,” she writes, “it is precisely sovereignty they must renounce.”

The point here is not to say that individual rights are of no importance to political systems, or to freedom more broadly. Rather, it suggests that a comprehensive freedom cannot flourish in systems in which individuals remain committed to sovereignty above all else. Freedom is not located within the individual, but rather in the systems, or community, within which an individual operates.

We do not envy the freedom a prisoner possesses to retreat into the recesses of their own mind, we envy the person who is free to leave their home, and is safe in doing so, because a system has been politically and socially established to make it as such.

When debates are being waged over freedom, we must begin with the acknowledgement that we (as individuals) are only ever as free as the broader communities in which we operate. Our own freedoms are contingent upon the political systems that we exist in, actively engage with, and mutually construct.

Assessing the disagreement, or linguistic impasse, which exists between those who take political action as central to securing freedom and those who take freedom to begin to where politics ends has certainly not fully allowed us to realise the notion of a square circle to which Arendt alludes. Though from here, we may be better equipped to engage in discourse when we inevitably find one conception of freedom being pinned against another.

We are luckily not resigned to let present linguistic impasses on the matter of freedom mark the end of meaningful discourse. Rather, they can mark the beginning, as we are able to make efforts to rectify impasses that turn on this single word. Importantly, we have more language and words at our disposal, and many methods by which to use them. It is vital that we do.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Violent porn and feminism

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan The Ethics Centre 1 SEP 2021

Does pornography, especially violent pornography, contribute to gender-based violence, and if so, is censorship the answer? Or can the pornographic industry coexist with the drive towards gender equality?

We occupy a world plagued by sexual and gender-based violence. The United Nations declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) asserts that such violence need be recognised as “a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women”.

Globally in 2017, 219 women were killed each day by either a member of their own family or by their own intimate partner. Debates about the complex causes of such violence and reasons for the persistence of gender inequality remain. The role that pornography may play in both the maintenance and propagation of these harms is one of many factors considered relevant to the debate. Specifically, ethicists are needed to address the question: Could pornography and feminism be compatible bedfellows after all?

Renowned feminist philosopher Catherine Mackinnon argues that pornography “works as primitive conditioning”, meaning that its content is likely to inform the desires and subsequent actions of its viewers. Mackinnon asserts that if pornographic images are violent, this is likely to result in unwanted sexual violence being inflicted onto others by pornography’s consumers.

Contemporarily, debate and disagreement persist regarding how pornography should be managed for adult audiences.

Various philosophers and feminist theorists, such as Mackinnon, argue in favour of some form of criminal action being taken against certain types of pornography due to its capacity to harm women. In 1983, Mackinnon, alongside feminist writer and activist Andrea Dworkin, brought forward an Antipornography Civil Ordinance which proposed that pornography needs to be treated as a violation of women’s civil rights. The pair aimed to remove the freedom of speech protections pornography had been granted under United States law. The ordinance was ultimately struck down by the courts.

Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

To this day, feminists remain largely divided over MacKinnon’s antipornography ordinance. Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

Calls to dismantle the industry of pornography are often taken to be synonymous with feminist action. In such cases, this action is thought to be the best means of protecting women from an industry rife with exploitation. Similarly, calls to cease pornographic productions are often thought to serve the function of preserving women’s dignity by allowing them to avoid careers centred around sexual objectification.

However, demands for censorship or a general production shutdown of pornographic films are also calls to severely limit the career opportunities and subsequently the financial resources of pornographic actresses. Doing so may risk further degrading these workers’ rights. The profitability and questionable legality of the porn industry often permits it to function below industry standard, resulting in inadequate worker protections being extended to porn actors and actresses.

Stoya is a female adult entertainer who has spoken openly about a form of feminism which she worries hates both sex work and pornography. She is concerned that female sexuality is only being embraced within narrow margins, neglecting the possibility that hardcore pornography may empower women, both actresses and viewers, rather than degrade them. Stoya argues that a contemporary feminism which celebrates women’s right to work and earn an independent wage is flawed if it simultaneously rebukes women who freely choose to perform in pornography to acquire that wage. For Stoya, performing in hardcore pornography (produced under fair working conditions) does nothing to degrade the status of female performers. Rather, it stands as a celebration of a tirelessly campaigned for and emancipated female sexuality.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared. Doing so puts these women at increased risk of assault and exploitation out of fear their allegations will not be trusted or that they will meet with legal consequences. Stoya herself brought forward rape charges against famous male pornstar James Deen, and she holds that the remedy to such injustices lies in improving workers’ rights and the legislative systems surrounding the industry of pornography, rather than in trying to shut down the industry altogether.

This lack of regulation constitutes an injustice far greater than the supposed, yet largely unarticulated, harm of women being free to use their naked bodies for profit. The mere existence of agential and passionate hardcore pornographic actresses importantly signals the beginnings of a world where women’s bodies are no longer policed in ways which unjustifiably align sex with shame and exploitation.

So long as the porn industry is made to function on par with other industry’s standards, there is no reason to consider the bodies of female pornographic actresses anymore degraded, or exploited, than non-pornographic actresses, tradespeople, or frontline healthcare workers.

Calls to censor or morally condemn pornography are often less concerned with the rights of pornographic actresses and more with the potentially negative impact pornography has on its consumers. There are concerns, for example, that viewing violent pornography may increase sexual assault rates, a causal link which is yet to be definitively established. However, even if particular depictions of women’s bodies were found to increase the likelihood that men assault women, it is not immediately apparent that the desirable solution would be to forbid those depictions.

This censorship style solution shares particular characteristics with victim blaming culture, in which victims are blamed for the actions of perpetrators. In both victim blaming and pro-censorship anti-porn positions, the onus of change is placed on those who are determined to be the cause of any given injustice. The pornographic actress, for example, is told she cannot continue to do her work, instead of alternative interventions being sought which target perpetrators who may have been inspired by viewing particular pornographic depictions. We do not think it suitable to tell women to wear more clothing to stop men raping them; why should matters of pornography be handled any differently?

There are more desirable, alternative solutions to address contemporary issues of misogyny. First is the formation and endorsement of a safe and responsible pornography industry where the agency and security of actors and actresses is guaranteed. Unfortunately there will always be room for exploitation and abuse, however, these risks can be mitigated by extending workers’ rights and fair working conditions to pornographic actors in the same way such rights are endowed to workers in other industries.

Content subscription service Onlyfans stands as a site moving the pornography industry in this direction by allowing performers greater control over their content and income. OnlyFans allows performers to safely and independently produce pornographic content. However, the platform hasn’t avoided trouble for hosting adult content: Onlyfans recently announced it would be banning explicit content in a bid to attract investors, only to reverse its decision within a week after outcry from users.

Ongoing periphery interventions are also required to address gender-based violence and gender inequality more generally, such as improved sex education curriculums which provide more comprehensive education on consent and respectful relationships to school age children.

Interventions such as bolstering the regulatory bodies surrounding pornography and improving sex-ed curriculums allows societies to place adequate accountability on those who commit or are at risk of committing acts of violence against women. These interventions should be favoured over those which risk undermining the agency of both female performers and consumers of pornography.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality. Theorists and feminists alike need to engage in critical discourse regarding where the onus of change need be placed. The porn industry, pornographic actresses and perpetrators of violence against women are all potential targets of this change. The decisions we make regarding what actions should be taken will determine whether or not pornography is compatible with contemporary feminism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

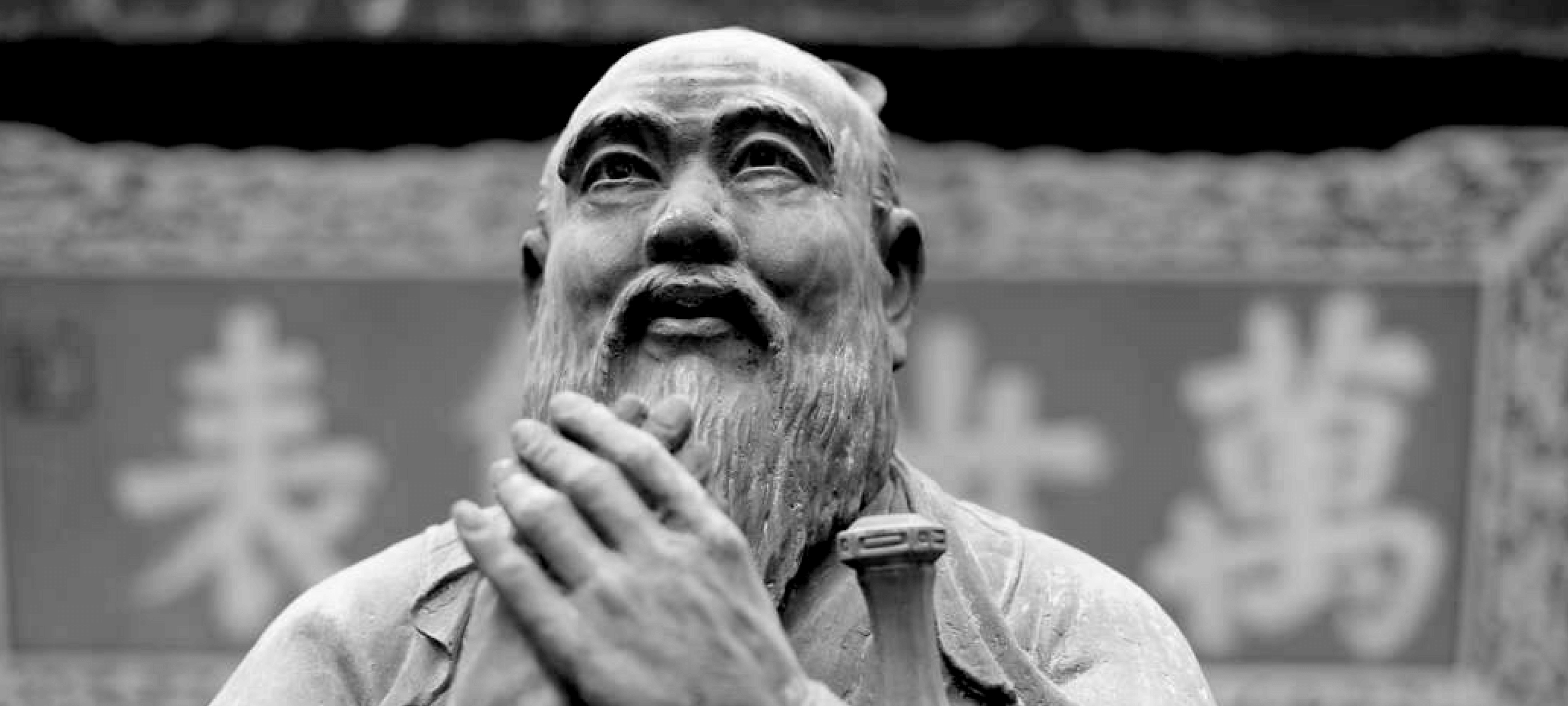

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What do we want from consent education?

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 11 MAY 2021

In mid-April this year a government-funded video was released which aimed to teach high-school aged Australians about sexual consent.

The video, which attempted to emphasise the importance of sexual consent by discussing the forced consumption of milkshakes, was widely criticised around the globe. It has since been removed from ‘The Good Society’ site, with secretary of the Department of Education Dr Michele Bruniges citing “community and stakeholder feedback” as reason for the action.

Widespread criticism of the video can be found online about the video’s sole use of metaphor to describe consent. Less present in the discussions is consensus on what a good consent education video would look like.

The underlying assumption in the video released by The Good Society is that issues of sexual consent can be managed by teaching adolescents that the rights of an individual are violated when an aggressor forces a ‘no’, or a ‘maybe’, into a ‘yes’. And, the video tells us, “that’s NOT GOOD!“.

Is it sufficient to tell adolescents to respect the rights of their peers in order to overcome issues of sexual violence? While rights may help us discuss what it is we want our societies to look like, they fail to assist us in getting others to care for, or value, the rights of others.

Sally Haslanger, Ford Professor of Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) argues that actions are shaped by culture, and that cultures are effectively networks of social meanings which work in a variety of ways to shape our social practices. To change undesirable social practices, cultural change must also occur.

For example, successfully managing traffic is not just achieved by passing traffic laws or telling drivers that breaking the law is ‘not good’. Instead, Haslanger tells us that it requires inculcating “public norms, meanings and skills in drivers”. That is, we need a particular type of culture for traffic laws to adequately do what it is we want them to do. Applying this idea to sexual consent, we see that we are required to educate populations about why violating the preferences of our peers is indeed ‘not good’, after all.

Skirting around the issue fails to provide resources to move our culture to better recognise the deep injustice and harms of sexual violence.

Vague, euphemistic videos will likely fail to play even a minor role in transforming our current culture into one with fewer instances of sexual violence. This is due largely to the fact that Australia is comprised of social and political systems which fail to take the violence experienced by women and girls seriously.

Haslanger suggests that interventions such as revised legislation and moral condemnation will be inadequate when enforced onto populations whose values are incompatible with the goals of such interventions.

Attempting to address issues of sexual misconduct indirectly – as seen by The Good Society video – are likely to be unsuccessful in creating long term behavioural change. Skirting around the issue fails to provide resources to move our culture to better recognise the deep injustice and harms of sexual violence.

As Haslanger tells us, so long as we are a culture which has misogyny embedded into it, social practices will continue to develop that cause people to act in misogynistic ways. We are required to reshape our culture in a way that changes the value and importance of women.

So long as we are a culture which has misogyny embedded into it, social practices will continue to develop that cause people to act in misogynistic ways.

So, what will shift and transform embedded cultural practices? A better approach advocates educating audiences why consent is valuable, not just how to go about getting it. A population which fails to value the bodily autonomy and preferences of each of its members equally is not a population that will go about acquiring consent in successful and desirable ways.

Quick fix solutions such as ambiguously worded videos on matters of consent are likely to do very little for adolescents in a school system absent of a comprehensive sexual education, and where conversations on sexual conduct and interpersonal relationships remain marginalised.

We need to aim to create a generation of adolescents who are taught why sexual consent is important and why they should value the preferences of their peers. A culture which continues to keep sex ‘taboo’ by failing to explicitly discuss sexual relationships and the reasons why disrespecting bodily autonomy is “NOT GOOD!” will be one which fails to resolve its endemic misogyny and disregard for the lives of women and girls.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are witnessing just how fragile liberal democracy is – it’s up to us to strengthen its foundations

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships