Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Jack Hume The Ethics Centre 8 DEC 2016

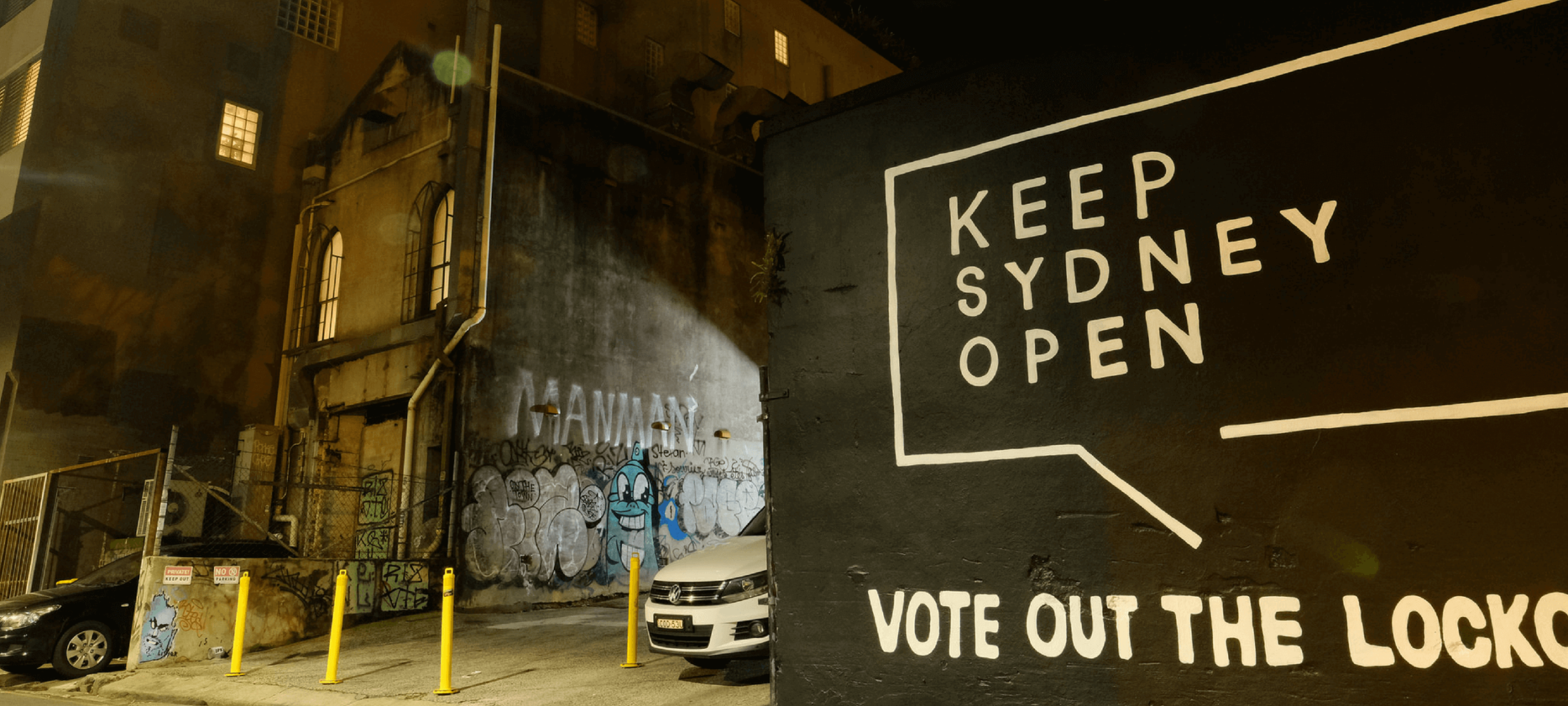

The New South Wales lockout laws were introduced in early 2014 in the wake of a great tragedy – the loss of human life to alcohol-fuelled violence.

Following the recommendations of an independent inquiry by Ian Callinan QC in 2016, the government decided to soften them. It shows that when we legislate in the wake of a tragedy, our judgement can be reactive. In the future, let’s measure our reactions against evidence.

When lockout laws were introduced in Sydney, alcohol related violence was on a downward trend. Even if people were afraid of becoming victims of violence, they were actually less likely to be attacked than in the past.

There is something to be learned from reflecting on the climate in which these laws were passed. We should be thinking about risks in terms of their likelihood, not in terms of how much we fear them. But that’s very hard, as we can see with another example – shark attacks.

People overestimate the likelihood of a shark attack in the same way they do other events they seriously fear, like terrorism and natural disasters. A study on Australian perception of sharks found that Sydneysiders believe shark attacks occur twice as often as they actually do, and fatal ones four times as often.

“Exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe they occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.”

This isn’t surprising. Research tells us we believe things are more likely to occur if we can easily call to mind examples of when they’ve occurred. And disturbing examples are easier to recall. The process of judging the probability of an event by how easy we find it to think of examples is known as the availability heuristic.

Emotional information is easier to remember, and so the availability heuristic has an interesting relationship with news coverage. Emotional news content prompts our attention, invariably placing demands on further coverage, which we will remember more easily.

News media is highly responsive to issues its audiences are interested in, and as a result those issues get more coverage. This pulls people into a feedback loop whereby their demands for further coverage lead them to believe events are more probable than they really are.

“Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line.”

For example, exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe crimes occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.

Knowing all this, we should expect people to overestimate the probability of events that provoke fear – violence, terrorism, plane crashes and natural disasters – particularly while they’re fresh in our memory. This effect is seen not just in how we speak and think about probability, but in how we act to protect ourselves, which brings us back to NSW policy.

Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line. Lockout laws are said to have been bad for Sydney’s culture and night-time economy. The public backlash forced the review that recommended loosening the reins of the lockout laws.

“Once news providers and their audience are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.”

The point is not whether lockout laws are effective in decreasing the threat of violence (which they have been in Sydney CBD), but the conditions through which they came about. These included media coverage on disturbing and unusual events – in particular, ‘one-punch’ killings – which caused fear and demanded attention, plus a campaign to increase awareness.

When the media reports on disturbing and unusual events at the same time that campaigns are run to increase awareness for them, the basic ingredients for a feedback between news media and its audiences are met. Once news providers and their audiences are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.

Shark nets are installed with the expectation of reducing the risk of shark attacks but they do this at the expense of marine life. They come as a response to the fact Australia has an above average incidence of shark attacks, which appear to be increasing. But let’s put this in perspective – the risk posed by sharks is still extremely low, accounting for two deaths in 2016 and one death in 2017.

The availability heuristic has unconscious components. Usually, people aren’t aware they’re estimating probability based on their fallible and selective memory. When people are unaware of how emotions, personal experiences and exposure to similar events can affect their judgements, they make unconsciously biased decisions.

Without appropriate consideration, people are at risk of basing important decisions on forces they aren’t consciously aware of. They may be led to support invasive or expensive regulations to protect themselves from risks that are highly unlikely. Where these regulations have undesirable side effects, like marine animal deaths, cultural damages to nightlife or the closure of businesses, this can mean real consequences for unreal problems.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Day trading is (nearly) always gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

David Pocock’s rugby prowess and social activism is born of virtue

BY Jack Hume

Jack studied Philosophy and Psychology at the University of Sydney, completing his Bachelor of Arts in 2017 with First Class Honours. He has supported The Ethics Centre's Advice & Education team in research capacities over the last two years, contributing to their work on cognitive bias in decision making, and ethics education in financial services. In 2018, he joined the Centre full-time as a Graduate Consultant. He brings insights from contemporary political philosophy, moral psychology and skills in qualitative research to consulting projects across a variety of sectors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Jack Hume The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2016

For the most part, we respect our colleagues and probably wouldn’t ever label them ‘sexist’ and certainly not ‘racist’. But gender and ethnic diversity in workplaces shows something is amiss.

Women fare worse than men across most measures of workforce equity. The Australian Government’s Gender Equality Agency report notes women who work full-time earn 16 percent less per week than men, constitute 14 percent of chair positions, 24 percent of directorships and 15 percent of CEO positions.

Women lose at both ends of the career lifecycle. Their average graduate salaries are 9 percent less than their male equivalents’ and their average superannuation balances 53 percent less.

Sociology, psychology and gender and cultural studies have all weighed in on the multiple causes of these inequalities, with much of the conversation converging around the role of ‘unconscious bias’ in decision-making.

Applicants with Indigenous, Chinese, Italian and Middle Eastern sounding names were seen to be systematically less likely to get callbacks than those with Anglo-Saxon names.

Studies in which people are asked to evaluate the capabilities and aptitudes of a job candidate show effects of implicit biases on job assessment. In a study mimicking hiring procedures for math related jobs, male candidates fared so much better than women that lower-performing males were chosen over better female candidates.

Similar effects have been seen with regard to race. In Australia, applicants with Indigenous, Chinese, Italian and Middle Eastern sounding names were less likely to get callbacks than those with Anglo-Saxon sounding names.

When biases become socially reinforced, individuals can come to see them as ‘reality’. Studies have shown women tend to believe they are worse at math than men and this belief has a negative impact on their performance.

In one study, a group of women were asked their gender prior to math tests and performed worse than the group who weren’t asked to disclose it. This phenomenon is called the ‘stereotype threat’ and it extends to racial beliefs. Two decades ago, a landmark study found that asking students of colour to identify their ethnicity prior to a test resulted in a substantially poorer grade.

This evidence suggests human resource departments might consider adopting hiring procedures that don’t require race, gender or even an applicant’s name be stated. Of course, at some point, the candidate will need a face-to-face interview, so this isn’t a perfect solution to bias- but it does reduce its influence.

Volunteering to learn more about diversity signifies a more general willingness to open organisational culture to people from different backgrounds.

Alongside systematic and procedural changes, we can help cultivate organisational willingness to combat inequality through diversity training. These training programs rose to prominence around a decade ago as a result of a wave of lawsuits against major US companies. However, as Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev explained in an article for the Harvard Business Review, they were dazzlingly unsuccessful — resulting in negative outcomes for Asians and Black women, whose representation dropped an average of five and nine percent, respectively.

Dobbin and Kalev suggest the major reason these programs failed is probably because they were usually mandatory. This suggests they were motivated more by risk aversion — ‘discriminate and you’ll be fired’ — than a genuinely held belief diversity is valuable. It’s not surprising systematic change didn’t occur under such conditions.

At the same time, companies who used voluntary diversity programs saw increases in black, Asian and Hispanic representation – even as the average was decreasing nationwide. Volunteering is most likely motivated by a belief that diversity is genuinely valuable — factors that seem far more effective in influencing workplace diversity, perhaps because they are genuine.

Science is yet to tell us whether we can actually reduce biases let alone erase them altogether. All the same, we can begin to mend workplace inequalities by actively engaging peoples’ will to change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership