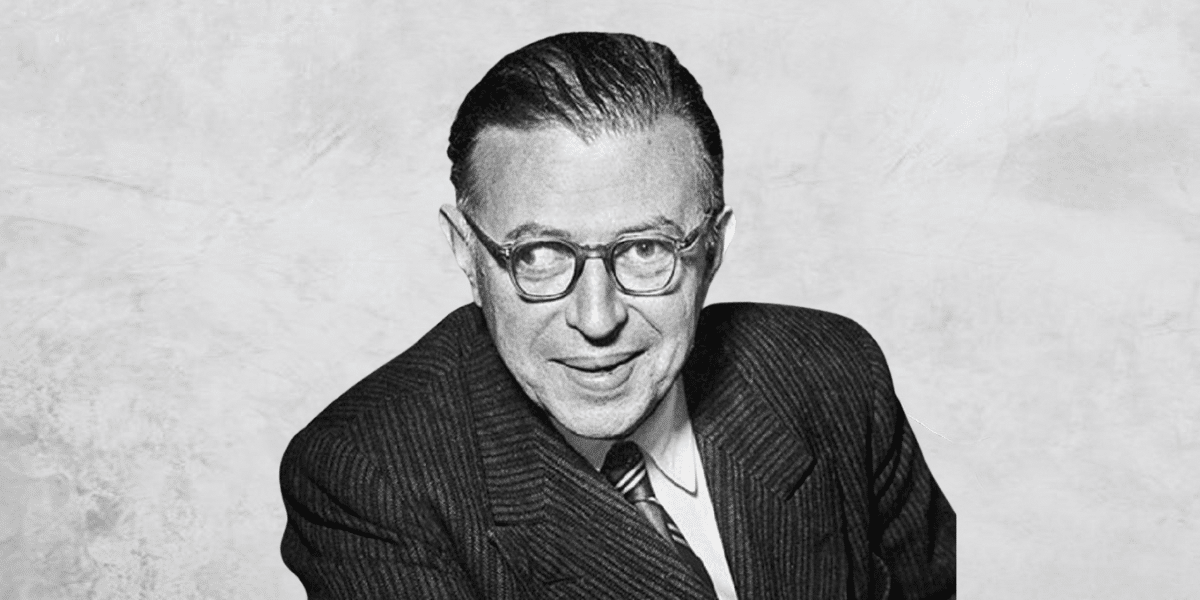

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) is one of the best known philosophers of the 20th century, and one of few who became a household name. But he wasn’t only a philosopher – he was also a provocative novelist, playwright and political activist.

Sartre was born in Paris in 1905, and lived in France throughout his entire life. He was conscripted during the war, but was spared the front line due to his exotropia, a condition that caused his right eye to wander. Instead, he served as a meteorologist, but was captured by German forces as they invaded France in 1940. He spent several months in a prisoner of war camp, making the most of the time by writing, and then returned to occupied Paris, where he remained throughout the war.

Before, during and after the war, he and his lifelong partner, the philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir, were frequent patrons of the coffee houses around Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. There, they and other leading thinkers of the time, like Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, cemented the cliché of bohemian thinkers smoking cigarettes and debating the nature of existence, freedom and oppression.

Sartre started writing his most popular philosophical work, Being and Nothingness, while still in captivity during the war, and published it in 1943. In it, he elaborated on one of his core themes: phenomenology, the study of experience and consciousness.

Learning from experience

Many philosophers who came before Sartre were sceptical about our ability to get to the truth about reality. Philosophers from Plato through to René Descartes and Immanuel Kant believed that appearances were deceiving, and what we experience of the world might not truly reflect the world as it really is. For this reason, these thinkers tended to dismiss our experience as being unreliable, and thus fairly uninteresting.

But Sartre disagreed. He built on the work of the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl to focus attention on experience itself. He argued that there was something “true” about our experience that is worthy of examination – something that tells us about how we interact with the world, how we find meaning and how we relate to other people.

The other branch of Sartre’s philosophy was existentialism, which looks at what it means to be beings that exist in the way we do. He said that we exist in two somewhat contradictory states at the same time.

First, we exist as objects in the world, just as any other object, like a tree or chair. He calls this our “facticity” – simply, the sum total of the facts about us.

The second way is as subjects. As conscious beings, we have the freedom and power to change what we are – to go beyond our facticity and become something else. He calls this our “transcendence,” as we’re capable of transcending our facticity.

However, these two states of being don’t sit easily with one another. It’s hard to think of ourselves as both objects and subjects at the same time, and when we do, it can be an unsettling experience. This experience creates a central scene in Sartre’s most famous novel, Nausea (1938).

Freedom and responsibility

But Sartre thought we could escape the nausea of existence. We do this by acknowledging our status as objects, but also embracing our freedom and working to transcend what we are by pursuing “projects.”

Sartre thought this was essential to making our lives meaningful because he believed there was no almighty creator that could tell us how we ought to live our lives. Rather, it’s up to us to decide how we should live, and who we should be.

“Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.”

This does place a tremendous burden on us, though. Sartre famously admitted that we’re “condemned to be free.” He wrote that “man” was “condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.”

This radical freedom also means we are responsible for our own behaviour, and ethics to Sartre amounted to behaving in a way that didn’t oppress the ability of others to express their freedom.

Later in life, Sartre became a vocal political activist, particularly railing against the structural forces that limited our freedom, such as capitalism, colonialism and racism. He embraced many of Marx’s ideas and promoted communism for a while, but eventually became disillusioned with communism and distanced himself from the movement.

He continued to reinforce the power and the freedom that we all have, particularly encouraging the oppressed to fight for their freedom.

By the end of his life in 1980, he was a household name not only for his insightful and witty novels and plays, but also for his existentialist phenomenology, which is not just an abstract philosophy, but a philosophy built for living.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships