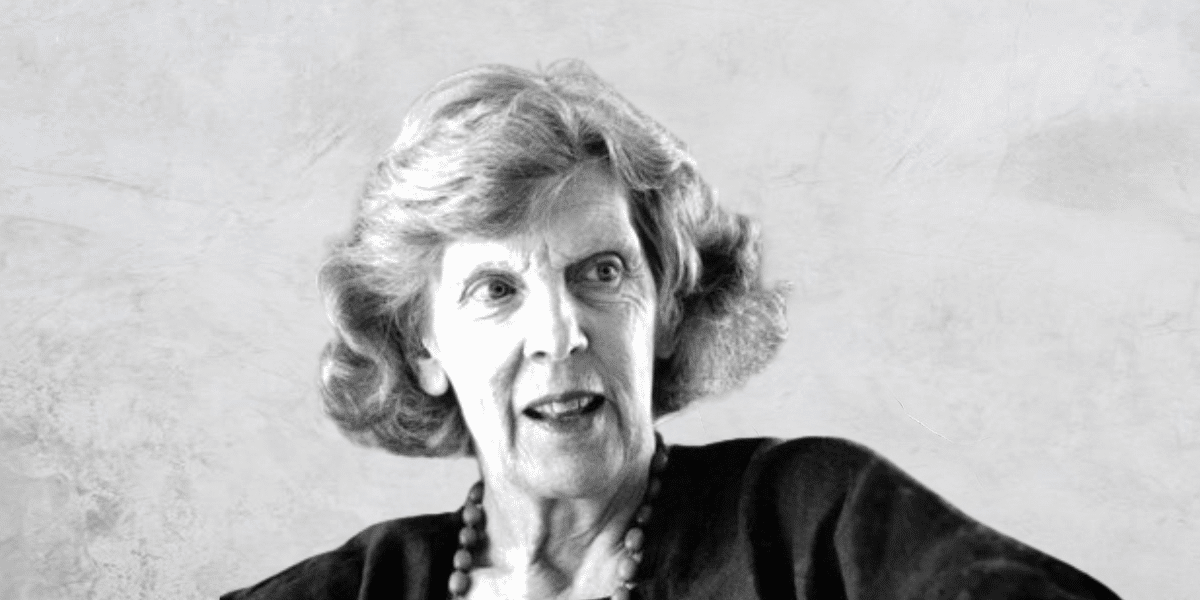

Philippa Foot (1920-2010) is one of the founders of contemporary virtue ethics, reviving the dominant Aristotelian ethics in the 20th century. She introduced a genre of decision problems in philosophy as part of the analysis in debates around abortion and the doctrine of double effect.

Philippa Foot was born in England in 1920. While receiving no formal education throughout her childhood, she obtained a place at Somerville College, one of the two women’s colleges at Oxford. After receiving a degree in 1942 in politics, philosophy and economics, she briefly worked as an economist for the British Government. Besides this, she spent her life at Oxford as a lecturer, tutor, and fellow, interspersed with visiting professorships to various American colleges, including Cornell, MIT, City University of New York and University of California Los Angeles.

Virtue ethics

In the philosophical world, Philippa Foot is best known for her work repopularising virtue ethics in the 20th century. Virtue ethics defines good actions as ones that embody virtuous character traits, like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. This is distinct from deontological ethical theories which encourage us to think about the action itself and its consequences or purpose instead of the kind of person who is doing the action.

“What I believe is that there are a whole set of concepts that apply to living things and only to living things, considered in their own right. These would include, for instance, function, welfare, flourishing, interests, the good of something. And I think that all these concepts are a cluster. They belong together.”

The doctrine of double effect

Imagine you are the driver of a runaway trolley that is barrelling down the tracks. You have the option to do nothing, and let five people die, or the option to switch the tracks and kill one person.

This is Philippa Foot’s famous trolley problem. This thought experiment encourages us to think about the moral differences between actively causing death (e.g. pulling a lever to get the trolley to change tracks) and passively or indirectly causing death (doing nothing, allowing the trolley to kill five people. Utilitarians might argue that five deaths is far less desirable than one death, but many people instinctively feel that actively causing a death has a different moral weight than doing nothing.

Perhaps Foot’s most influential paper is The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect, published in 1967. Here, she explains what is called the Doctrine of the Double Effect, which explains why some very bad actions (like killing) might be permissible because of their potentially positive outcomes. The trolley problem is one example of the doctrine of double effect, but she also uses various other cases.

“The words “double effect” refer to the two effects that an action may produce: the one aimed at, and the one foreseen but in no way desired. By “the doctrine of the double effect” I mean the thesis that it is sometimes permissible to bring about by oblique intention what one may not directly intend.”

For example, what if one person needed a large dose of a rare medicine to save their life, but that same amount of medicine could save the lives of five others who each needed less? Would we think that the “oblique intention” of a nurse who administers the medicine to one person instead of the five people is justified?

Foot finds that it would be wise to save the five people by giving them each a one-fifth dose of the medicine. However, she encourages us to interrogate why this feels different from the organ donor case, where we save five people who need organ transplants by sacrificing one person.

“My conclusion is that the distinction between direct and oblique intention plays only a quite subsidiary role in determining what we say in these cases, while the distinction between avoiding injury and bringing aid is very important indeed.”

When the trolley problem is taken to its logical conclusion, these fallacies become even more obvious. As John Hacker-Wright writes, the trolley problem “raises the question of why it seems permissible to steer a trolley aimed at five people toward one person while it seems impermissible to do something such as killing one healthy man to use his organs to save five people who will otherwise die.”

Foot has also contributed to moral philosophy with her writing on determinism and free will, reasons for action, goodness and choice, and discussions of moral beliefs and moral arguments.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture