Big Thinker: Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE—399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy.

Stonemason, soldier, citizen, philosophy’s first ‘martyr’, Socrates helped shape one of the major intellectual foundations on which Western civilisation has been built. Yet, no work of philosophy bears his name as the author. All we know of him is derived from the work of others – especially Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes.

The rise of ethics

Prior to Socrates, ancient philosophy tended to focus on questions that today might be considered the domain of physics. ‘Pre-Socratic’ philosophers tended to focus on fundamental questions about the nature of the universe – like the building blocks of matter or the nature of time and motion.

When Socrates came along, he proposed a completely different set of questions for philosophical deliberation. He drew attention away from questions about how the world is and towards questions about how we are to be in the world. While he made valuable contributions to the evolution of thought about epistemology and politics, it is this turn toward ethics that introduced a fresh practical dimension to philosophy.

Earlier philosophical debates of Thales, Anaximander and Democritus, for example, were all theoretical. Human knowledge and understanding might have advanced, but nothing in the world was directly changed by their deliberations.

Socrates’ focus on ethics was intended to generate practical outcomes. He expected philosophical work might lead to a change in both attitudes and (importantly) actions of people. In turn, this was intended to produce effects in the world. Although we have only come to see Socrates through the eyes of others, his friends (like Plato and Xenophon) and foes (like Aristophanes) agree he wished to have an impact on the people around him and the kind of society they were creating as a result of their choices.

What friends and foes disagreed on was Socrates’ motivation. His critics lumped him in with the Sophists who were looked down on as philosophical guns for hire.

A new focus on ethics repositioned philosophy as something relevant to everyday life. Socrates’ core question, ‘What ought one to do?’ does not apply in a limited set of circumstances. It is a question of general application to any situation where a choice is to be exercised – and is applicable to every person, whatever their station in life.

In some sense, this is what made Socrates such a troublesome – or dangerous – person. In one fell swoop, he brought philosophy into the agora (the marketplace), making it relevant and accessible to people of all ages and degrees.

This upset hierarchies and orthodoxies. As we know, a gadfly is rarely welcome. Socrates was eventually executed for crimes of ‘impiety’ and ‘corrupting the youth’ – in short, for teaching and encouraging them to question established norms and think for themselves.

The virtue of ‘constructive ignorance’

On being asked who the wisest person in Athens was, the Oracle of Delphi nominated Socrates. Socrates was astounded – he believed himself to know nothing. To prove his relative ignorance, Socrates sought to find wiser folk amongst the citizens of Athens, questioning them at length about the nature of things like justice and love.

His questioning had practical implications. At that time in democratic Athens, citizens were actively involved in enacting laws or judgements in the courts.

In the end, Socrates came to believe the Oracle of Delphi was correct – but only because his superior wisdom lay in his realising the limits of his knowledge.

Along the way to this realisation, Socrates developed the process of elenchus (the ‘Socratic method’). It is a distinctive form of questioning designed to open space for insight and self-knowledge. The idea we have much to learn about ourselves and the world might suggest we are ignorant. Such a view could position the Socratic method of questioning as a mean spirited exercise. Those subjected to it did not necessarily enjoy the experience or see it in a positive light. This no doubt contributed to the belief Socrates was an impious trouble maker.

The importance of the examined life

Although Socrates contributed many insights that are still drawn upon today (but not necessarily accepted), one of his most famous and profound is his claim that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’.

This claim goes beyond being a recommendation we should think before we act – which may be a prudent thing to do. Socrates is attempting to draw our attention to a deeper truth about the human condition. He encourages us to participate in a form of being that has the capacity to transcend the requirements of instinct and desire in order to make conscious – that is, ethical – choices. Socrates claimed if we fail to do this, we live a lesser life.

One of the effects of examination is, according to Socrates, the development of phronesis (practical wisdom) which is the foundation for virtue. For Socrates (and later for Aristotle – in a slightly different form), the possession of virtue is not just a matter of interior orientation. It is essential to being able to see the world as it is and be able to make good decisions.

Like Aristotle, Socrates sees vice as the source of defective vision. Socrates thought people make bad choices and do bad things out of ignorance. He thought if people could only ‘see’ what is good, they would choose it.

This all finally comes together in the way Socrates challenged the status quo. To live an examined life is to reject things ought to be done just because they have always been done.

Instead, Socrates is an early exponent of an inner voice that (in Socrates’ case) is supposed to have warned him against making an error. Socrates called this voice his ‘daimōnic sign’ – something Aquinas would call ‘conscience’ over a thousand years later.

It may be difficult to distinguish the real Socrates from the versions of the man created by others – which were either celebratory or lampooning. But this we know. When given the chance to escape and avoid the sentence of death imposed on him by the Athenians, Socrates chose to stay. In defence of his ideas and in conformance with his ideals Socrates drank the hemlock and died.

He can hardly have imagined the impact he would have on the world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2017

Dennis Altman (1943—present) is an internationally renowned queer theorist, Australian professor of politics and current Professorial Fellow at La Trobe University.

Beginning his intellectual career in the 1970s, his impact on queer thinking and gay liberation can be likened to Germaine Greer’s contributions to the women’s movement.

Much of Altman’s work explores the differences between gay radical activists who question heteronormative social structures like marriage and nuclear family, and gay equality activists who want the same access to such structures.

“Young queers today are caught up in the same dilemma that confronted the founders of the gay and lesbian movements: Do we want to demonstrate that we are just like everyone else, or do we want to build alternatives to the dominant sexual and emotional patterns?”

Divided in diversity, united in oppression

Altman’s influential contribution to gay rights began with his first of many books, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. The 1971 text has been published in several countries and is still widely read today. It is often regarded as an uncannily correct prediction of how gay rights would improve over the decades – something that would have been difficult to imagine when the first Sydney Mardi Gras was met with police violence.

Altman predicted homosexuality would become normalised and accepted over time. As oppressions ceased, and liberation was realised, sexual identities would become less important and the divisions between homosexual and heterosexual would erode. Eventually, openly gay people would come to be defined the way straight people were – by characteristics other than their sexuality like their job, achievements or interests.

Despite gay communities being home to diversity and division, the shared experience of discrimination bonded them, Altman argued. Much like women’s and black civil rights advocates could testify, oppression has an upside – it forms communities.

End of the homosexual?

Altman’s 2013 book The End of the Homosexual? follows on from the ideas in his first. It is often described as a sequel despite the 40 years and several other publications between the two. He wrote it at a time when same sex marriage was beginning to be legalised around the world.

Altman recently reflected on his old work and said he was wrong to believe identity would become less important as acceptance grew but right to predict being gay would not be people’s defining characteristic.

He has come across as both happy and disappointed by the normalisation of same sex relationships. While massive reductions in violence and systemic discrimination is something you can only celebrate, Altman almost mourns the loss of the radical roots of gay liberation that formed in response to such injustices.

Without the oppressions of yesteryear, what binds diverse people into gay communities today? What distinguishes between a ‘gay lifestyle’ and a ‘straight lifestyle’ when they share so many characteristics like marriage, children, and general social acceptance?

Of course, all things are still not equal today. While people in the West largely enjoy safety and equality, people in countries like Russia are experiencing regressions. Altman hopes gay liberationists could have impact there.

Same sex marriage

Although he’s considered a pioneer in queer theory, a field that questions dominant heterosexual social structures, Altman does not support same sex marriage.

Some people might feel a sense of betrayal that such a well respected gay public intellectual has not put his influence behind this campaign. But Altman’s lack of support is completely consistent with the thinking he has been sharing for decades. Like a radical women’s liberationist, he has reservations about marriage itself – whether it’s same sex or opposite sex.

Altman takes issue with traditional marriage’s “assumption that there is only one way of living a life”. He has long been concerned the positioning of wedlock as the norm forgets all the people who are not living in long term, monogamous relationships. He argues marriage isn’t even all that normal in Australia anymore with single person households growing faster than any other category.

Altman was with his spouse for 20 years until death parted them. While that may sound like a marriage, the role of state and Church deeply bothers him, and so they were together without the blessings of those institutions. He has expressed confusion over the popular desire to be approved by the state or religious bodies that do not want to sanction same sex relationships. It’s because he doesn’t consider same sex marriage a human rights issue, when compared to things like starvation, oppression, and other forms of suffering.

Nevertheless, Altman recognises the importance of equal rights and understands why marriage for heterosexuals and not homosexuals is unfair. True to form he continues to question the institution itself by flipping the marriage equality argument on its head. He advocates for “the equal right not to marry”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

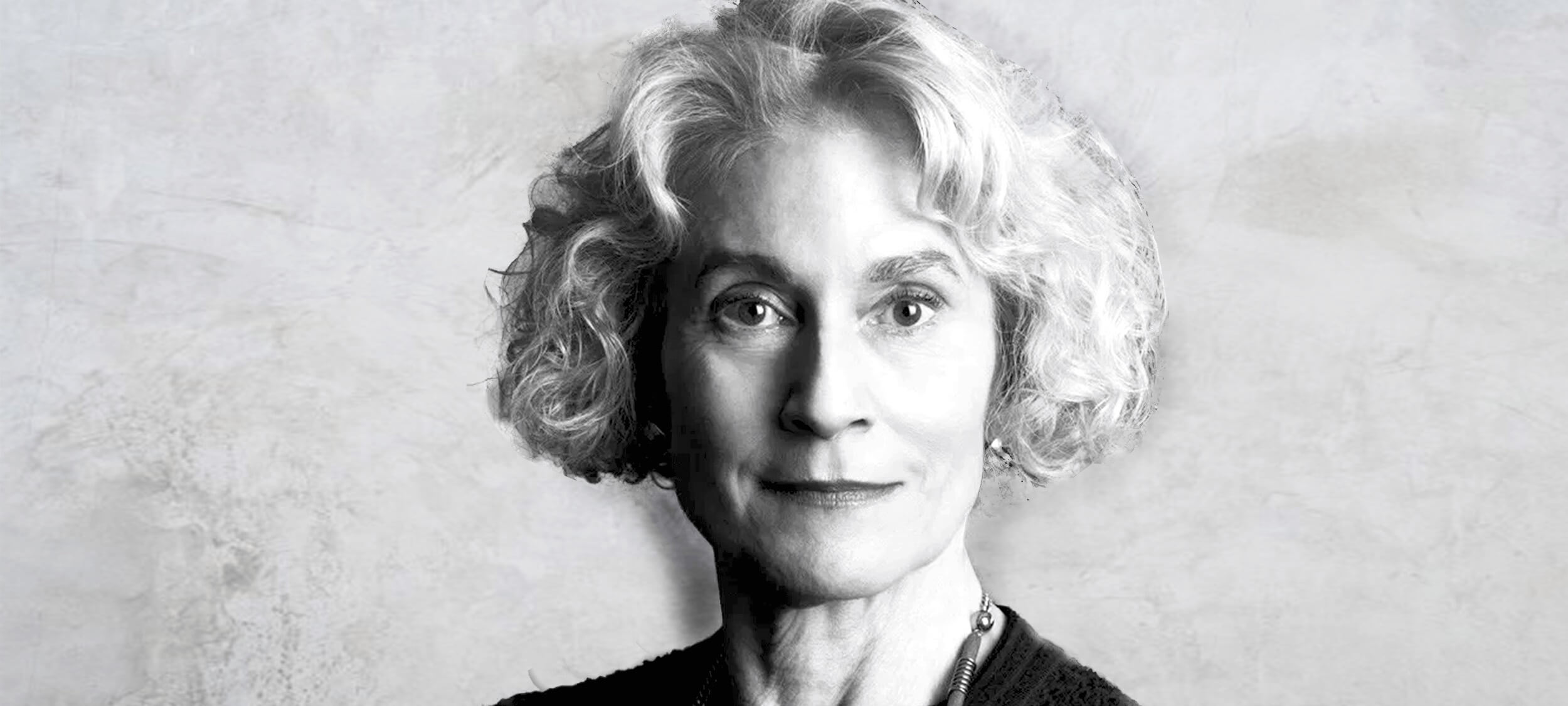

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum (1947—present) is one of the world’s most influential living moral philosophers.

She has published on a wide range of topics, from tragedy and vulnerability, to religious tolerance, feminism and the role of the emotions in political life. Nussbaum’s work combines rigorous philosophy with insights from literature, history and law.

Our happiness is largely beyond our control

Nussbaum takes issue with people like the Stoics and Immanuel Kant, who suggest there is no place for emotion within ethics. They believe ethics is about the things we can control. It’s about the things that can’t be lost or taken away from us, like our thoughts and our virtues.

For instance, in his Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant claimed even if bad luck or circumstance meant you were unsuccessful in everything you tried to do, so long as you acted with a “good will”, your actions would still “shine like a jewel”.

By contrast, Nussbaum believes the fact our intentions, desires and hopes can be thwarted by circumstances tells us something really important about flourishing (that’s philosophy speak for living the good life). Specifically, that it’s vulnerable and fragile.

She may have had Kant’s writing in mind when she wrote the ethical life “is based on a trust in the uncertain and on a willingness to be exposed; it’s based on being more like a plant than like a jewel, something rather fragile, but whose very particular beauty is inseparable from its fragility”.

Risk is a scary notion in our society. We don’t like thinking about it and we’re not good at judging it accurately. Part of that is because we don’t like uncertainty. But Nussbaum encourages us to reframe our attitude to vulnerability, seeing it as a unique aspect of what it means to be human.

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control.”

Politics doesn’t work without emotion

Most political philosophers and commentators are wary of the place of emotion in politics. When we think about the role of emotions in politics, it’s easy to focus on fear, disgust, envy and the ways they can corrupt our political life. It’s natural to assume politics would be better without the emotion, right?

Not according to Nussbaum. She suggests scrubbing politics clean of emotion would be like throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Yes, we need to be wary of the role of emotions in politics, but we couldn’t survive without them.

For one thing, it’s emotions like love and compassion that translate abstract concepts like truth and justice into real and lasting connections with particular groups and people. Ideas like human dignity capture what we all have in common but strong democracies tend to respect what makes different groups and people unique.

Emotions help us to cultivate a healthy balance between our attachments to ideas and institutions and our connection to particular places, people and histories. For Western democracies struggling to deal with different cultural groups and ideologies, Nussbaum’s view may help strike a balance between society-wide ideals and particular cultural differences.

What’s more, Nussbaum notes, political systems have always cultivated the emotions that serve them best. For example, monarchies cultivate childlike emotions of dependence and dictatorships often trade on a combination of nationalism and fear. These emotions create unity around a common political identity – albeit in ways people find problematic.

There’s promising terrain here, Nussbaum says, because if we can work out the emotions that best serve democratic life, we can then cultivate these emotions and create better citizens.

She thinks we can do this through ritual, public investments in art and a living sense of cultural and national history (she offers the rewriting of America’s founding fathers in Hamilton as a good example of this).

Nussbaum advises we can foster the emotions for citizenship with whatever “helps us to see the uneven and often unlovely destiny of human beings in the world with humour, tenderness, and delight, rather than with absolutist rage for an impossible sort of perfection”.

Educate for citizenship, not profitability

In Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, Nussbaum targets the education system. She gives an ominous diagnosis:

Thirsty for national profit, nations, and their systems of education, are heedlessly discarding skills that are needed to keep democracies alive. If this trend continues, nations all over the world will soon be producing generations of useful machines, rather than complete citizens who can think for themselves, criticize tradition, and understand the significance of another person’s sufferings and achievements. The future of the world’s democracies hangs in the balance.

Nussbaum believes there is a crucial role for the education system – from early school to tertiary – in building a different kind of citizen. Rather than economically productive and useful, we need people who are imaginative, emotionally intelligent and compassionate.

She is also critical of the ‘No Child Left Behind’ approach to education in the United States, which put increasing pressure on schools to improve outcomes. They wanted to know test scores were improving, believing better education outcomes would help break the cycle of poverty. However, in focussing on outcomes, Nussbaum believes they prioritised memorising over the kind of education she thinks democracies need – philosophy.

You might be sceptical whether people stuck in a cycle of poverty need an education offering philosophical skills. The pressing need to be economically useful and employable can be seen as more urgent and important with good reason. It’s likely there’s a compromise to be struck here, but Nussbaum’s work is still important.

It provides us with an alternative model of education and helps us see the beliefs underpinning our current attitudes to education.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

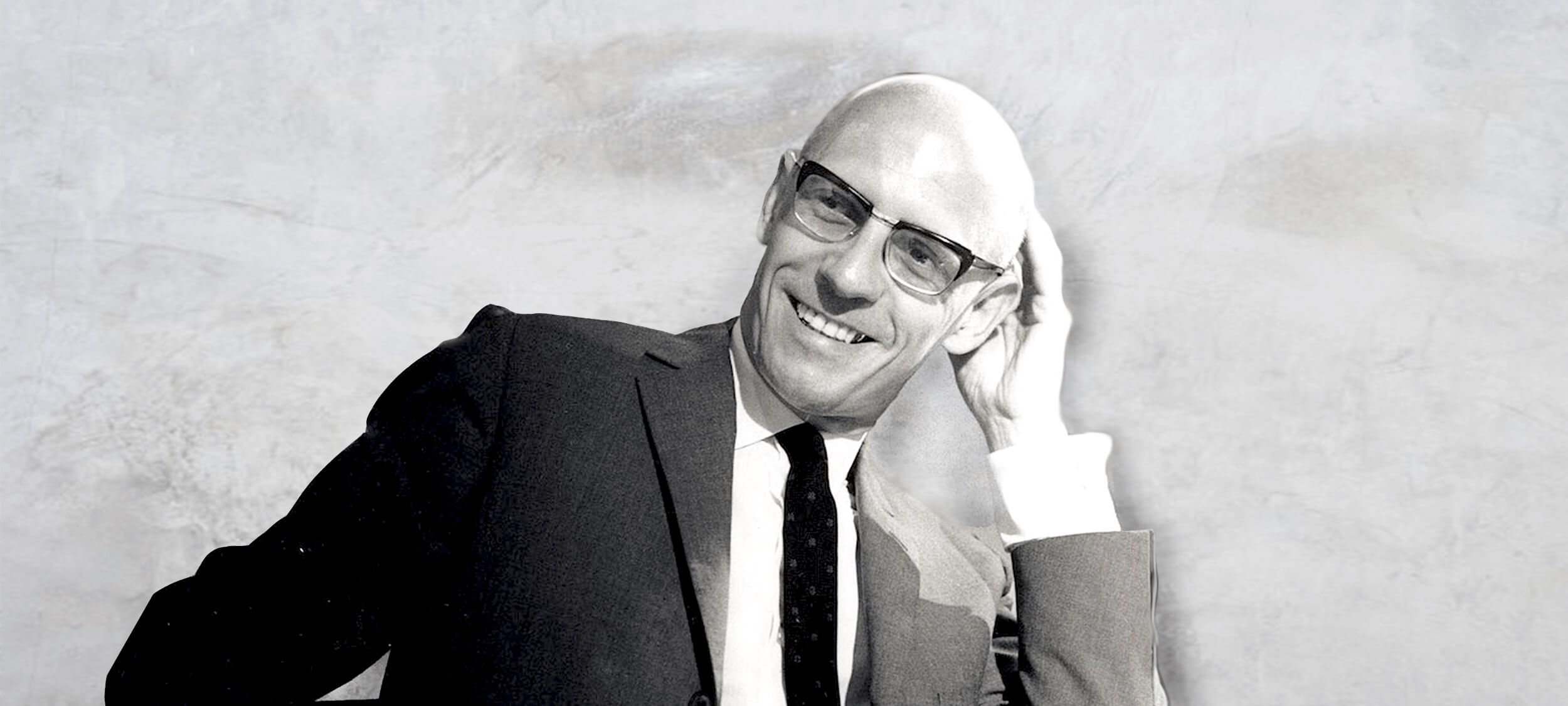

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 13 JUL 2017

Michel Foucault (1926—1984) was a French philosopher, historian and psychologist whose work explored the underlying power relationships in a range of our modern institutions.

Given Foucault’s focus on the ways institutions wield power over us, and that trust in institutions is catastrophically low around the world today, it’s worth having a look at some of the radical Frenchman’s key ideas.

History has no rhyme or reason

At the centre of Foucault’s ideas is the concept of genealogy – the word people usually use when they’re tracing their family history. Foucault thought all of history emerged in the same way a family does – with no sense of reason or purpose.

Just like your existence was the result of a bunch of random people meeting and procreating over generations, he thought our big ideas and social movements were the product of luck and circumstance. He argued what we do is both a product of the popular ways of thinking at the time (which he called rationalities) and the ways in which people talked about those ideas (which he called discourses).

Today Foucault might suggest the dominant rationalities were those of capitalism and technology. And the discourse we use to talk about them might be economics because we think about and debate things in terms their usefulness, efficiency and labour saving. Our judgements about what’s best are filtered through these concepts, which didn’t emerge because of any conscious historical design, but as random accidents.

You might not agree with Foucault. There are people who believe in moral progress and the notion our world is improving as time goes on. However, Foucault’s work still highlights the powerful sense in which certain ideas can become the flavour of the month and dominate the way we interpret the world around us.

For example, if capitalism is a dominant rationality, encouraging us to think of people as economic units of production rather than people in their own right, how might that impact the things we talk about? If Foucault is right, our conversations would probably centre on how to make life more efficient and how to manage the demands of labour with the other aspects of our life. When you consider the amount of time people spend looking for ‘life hacks’ and the ongoing discussion around work/life balance, it seems like he might have been on to something.

But Foucault goes further. It’s not just the things we talk about or the ways we talk about them. It’s the solutions we come up with. They will always reflect the dominant rationality of the time. Unless we’ve done the radical work of dismantling the old systems and changing our thinking, we’ll just get the same results in a different form.

Care is a kind of control

Although many of Foucault’s arguments were new to the philosophical world when he wrote them, they were also reactionary. His work on power was largely a response to the tendency for political philosophers to see power only as the relationship between the sovereign and the citizen – or state and individual. When you read the works of social contract theorists like Thomas Hobbes and Jean Jacques Rousseau, you get the sense politics consists only of people and the government.

Foucault challenged all this. He acknowledged lots of power can be traced back to the sovereign, but not all of it can.

For example, the rise of care experts in different fields like medicine, psychology and criminology creates a different source of power. Here, power doesn’t rest in an ability to control people through violence. It’s in their ability to take a person and examine them. In doing so, the person is objectified and turned into a case (we still read cases in psychiatric and medical journals now). This puts the patients under the power of experts who are masters of the popular medical and social discourses at the time.

What’s more, the expert collects information about the patient’s case. A psychiatrist might know what motivates a person’s behaviour, what their darkest sexual desires are, which medications they are taking and who they spend their personal time with. All of this information is collected in the interests of care but can easily become a tool for control.

A good example of the way non-state groups can be caring in a way that creates great power is in the debate around same sex marriage. Decades ago, LGBTI people were treated as cases because their sexual desires were medicalised and criminalised. This is less common now but experts still debate whether children suffer from being raised by same sex parents. Here, Foucault would likely see power being exercised under the guise of care – political liberties, sexuality and choice in marital spouse are controlled and limited as a way of giving children the best opportunities.

Prison power in inmate self-regulation

Foucault thought prisons were a really good example of the role of care in exercising power and how discourses can shape people’s thinking. They also reveal some other unique things about the nature of power in general and prisons more specifically.

In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault observed a monumental shift in how society dealt with crime. Over a few decades, punishments went from being public, violent spectacles like beheadings, hangings and mutilations to private, clinical and sterile exercises with the prison at the centre of it all. For Foucault, the move represented a shift in discourse. Capital punishment and torture were out, discipline and self-regulation were in.

He saw the new prison, where the inmates are tightly managed and regulated by timetables – meal time, leisure time, work time, lights out time – as being a different form of control. People weren’t in fear of being butchered in the town square anymore. The prison aimed to control behaviour through constant observation. Prisoners who were always watched, regulated their own behaviour.

This model of the prison is best reflected in Jeremy Bentham’s concept of the panopticon. The panopticon was a prison where every cell is visible from a central tower occupied by an unseen guard. The cells are divided by walls so the prisoners can’t engage with each other but they are totally visible from the tower at all times. Bentham thought – and Foucault agreed – that even though the prisoners wouldn’t know if they were being watched at any moment, knowing they could be seen would be enough to control their behaviour. Prisoners were always visible while guards were always unseen.

Foucault believed the panopticon could be recreated as a factory, school, hospital or society. Knowing we’re being watched motivates us to conform our behaviours to what is expected. We don’t want to be caught, judged or punished. The more frequently we are observed, the more likely we are to regulate ourselves. The system intensifies as time goes on.

Exactly what ‘normality’ means will vary depending on the dominant discourse of the time but it will always endeavour to reform prisoners so they are useful to society and to the powerful. That’s why, Foucault argued, prisoners are often forced to do labour. It’s a way of taking something society sees as useless and making it useful.

Even when they’re motivated by care – for example, by the belief that work is good for prisoners and helps them reform – the prison system serves the interests of the powerful in Foucault’s eyes. It will always reflect their needs and play a role in enforcing their vision of how society should be.

You needn’t accept all of Foucault’s views on prisons to see a few useful points in his argument. First, prisons haven’t been around forever. There are other ways of dealing with crime we could use but choose not to. Why do we think prisons are the best? What are the beliefs driving that judgement?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2017

Simone de Beauvoir (1908—1986) was a French author, feminist and existential philosopher. Her unconventional life was a working experiment of her ideas – that one creates the meaning of life through free and authentic choices.

In a cruel confirmation of the sexism she criticised, Beauvoir’s work is often seen as less important than that of her partner, Jean Paul Sartre. Given the conclusions she drew were hugely influential, let’s revisit her ideas for a refresher course.

Women aren’t born, they’re made

Beauvoir’s most famous quote comes from her best-known work, The Second Sex: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”.

By this she means there is no essential definition of womanhood. Women can be anything, but social norms work hard to fit them into a particular kind of femininity. These social norms are patriarchal and born out of the male gaze.

The Second Sex argues that it’s men who define what women should be. Because men have always held more power in society, the world looks the way men want it to look. An obvious example is female beauty.

Beauvoir holds that through norms around removing body hair, makeup and uncomfortable fashion, women restrict their freedom to serve the male gaze.

This objectification of women goes deeper, until they aren’t seen as fully human. Men are seen as active, free agents who are in control of their lives. Women are described passively. They need to be protected, controlled or rescued.

It’s true, she thinks, that women aren’t always seen as passive objects, but this only happens when they impersonate men.

“Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.”

For Beauvoir, women are always cast into the role of the Other. Who they are matters less than who they’re not: men. This is an enormous problem for the existentialist, for whom the purpose of life is to freely choose who they want to be.

Everyone has to create themselves

As an existentialist, Beauvoir believed people need to live authentically. They need to choose for themselves who they want to be and how they want to live. The more pressure society – and other people – place on you, the harder it is to make an authentic choice.

Existentialists believe no matter the amount of external pressure, it is still possible to make a free choice about who we want to be. They say we can never lose our freedom, though a range of forces can make it harder to exercise. Plus, some people choose to hide from their freedom in various ways.

Some of us hide from our freedom by living in bad faith, embracing the definitions other people put on us. Men are free to reject the male gaze and stop imposing their desires onto women but many don’t. It’s easier, Beauvoir thinks, to accept the social norms we’re born into. To live freely and authentically is the greater struggle.

The importance of freedom led Beauvoir to suggest liberated women should not try to force other women to live their lives in a similar way. If a small group of women choose to reject the male gaze and define womanhood in their own way, that’s great.

But respecting other people means allowing them to live freely. If other women don’t want to join the feminist mission, Beauvoir believed they should not be forced or pressured to do so. This is important advice in an age where online shaming is often used to force people to conform to popular social views.

We’re as ageist as we are sexist

Later in life, Beauvoir applied her arguments about women in The Second Sex to the plight of the elderly. In The Coming of Age, she argued that we make assumptions and generalisations about the elderly and ageing, just like we do about women.

To her, it is as wrong to ‘other’ women because they are different from men, as it is to ‘other’ the elderly because they are different from the young. Feminist philosopher Deborah Bergoffen explains Beauvoir’s view: “As we age, the body is transformed from an instrument that engages the world into a hindrance that makes our access to the world difficult”.

Like women in The Second Sex, the elderly remain free to define themselves. They can reject the idea that physical decline makes them unable to function as authentic human beings.

In The Coming of Age, we see some of the foundations of today’s discussions about ageism and ableism. Beauvoir urges us to come back to a simple truth: the facts of our existence – what our bodies are like, for example – don’t have to define us.

More importantly, it’s wrong to define other people only by the facts of their existence.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Agape

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

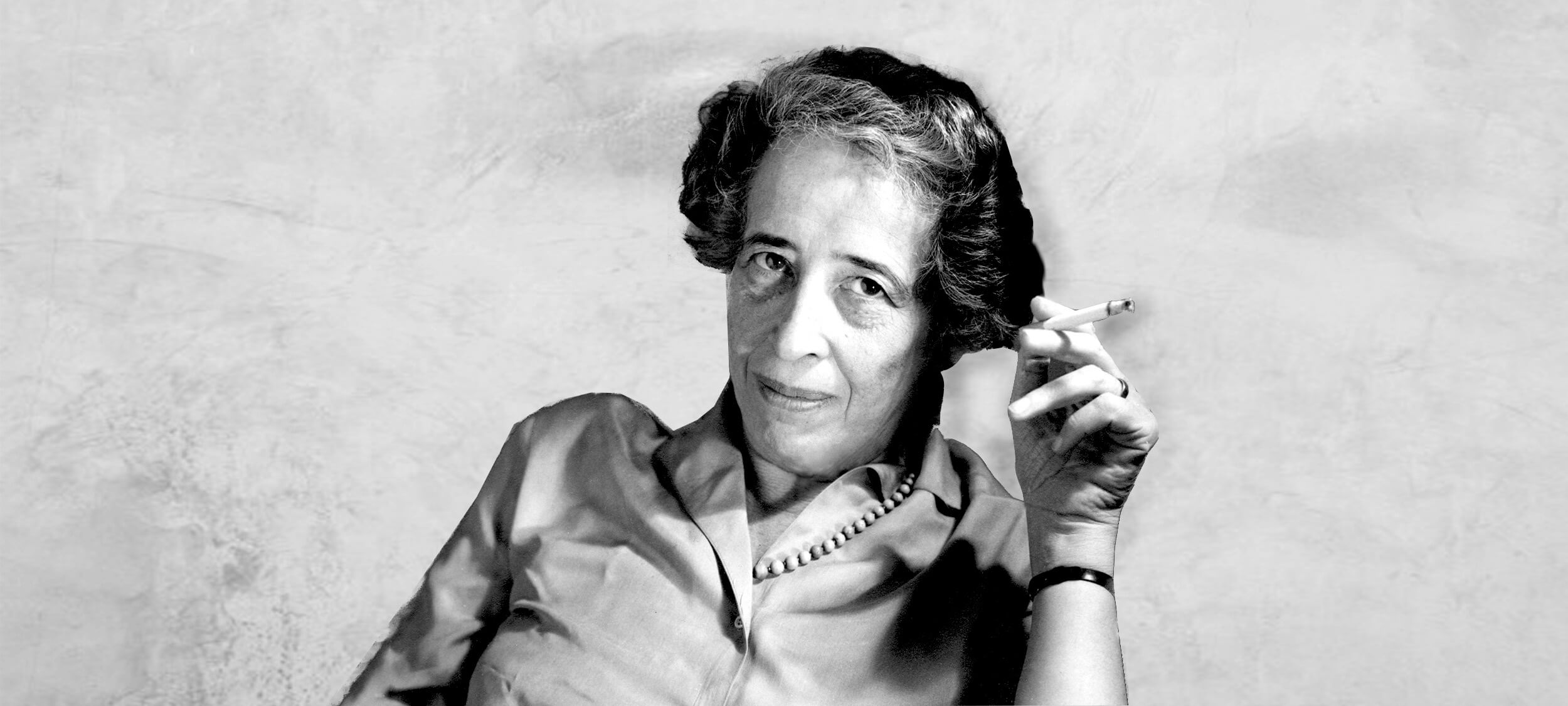

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades.

We are still learning from this seminal political theorist. Her book The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon in 2017, more than 60 years after it was first published.

Evil doesn’t need malicious intentions

Arendt’s most well known idea is “the banality of evil”. She explored this in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat who shared the first name of Hitler, Adolf Eichmann. This later became a book called Eichmann in Jerusalem: Reflections on the Banality of Evil.

In Eichmann, Arendt found a man whose greatest crime was a lack of thinking. His role was to transport Jewish people from German occupied areas to concentration camps in Poland. Eichmann did not kill anyone first hand. He was not involved in designing Hitler’s final solution. But he oversaw the trains that took millions of people to their deaths. They were gassed in chambers or died along the way or in camps due to starvation, overwork, illness, cold, heat, or brutality. Eichmann’s only defence for his involvement in this atrocity was obedience to the law and fulfilling his duty.

Eichmann was so steadfast with this line of reasoning he even referenced the philosopher Immanuel Kant and his theory of moral duty. Kant argued morality was acting on your obligations, not your emotions or what will bring you benefit. For Kant, the person who helps the beggar out of empathy or a belief assisting is a pathway to heaven is not doing an act of good. Kant felt everyone is morally obliged to help the beggar, and they are especially virtuous if they act on this duty despite feeling repulsed or no rewarding sense of doing good.

This does not really suit Eichmann’s argument because Kant was emphasising our ability to reason above emotion. This is precisely where Eichmann failed. We can only guess but it seems likely he did his job without asking questions while feeling a sense of comfort in the safety of his salary and senior position during volatile times.

Arendt believed it was this lack of true thinking and questioning that paved the way to genocide. Evil on the scale of Nazism required far more Adolf Eichmanns than Adolf Hitlers.

Totalitarianism needs political apathy

In studying the causes of WWII, Arendt came across “the masses”. She believed totalitarian regimes needed this to succeed.

By “the masses”, she meant the enormous group of people who are politically disconnected from other members of society. They don’t identify with a particular class, religion, or group. Their lack of group membership deprives them of common interests to demand from government. These people have no interest in politics because they don’t have political clout. They are an unorganised cohort with different, often conflicting desires whose needs are easily disregarded by politicians.

But although these people take no active interest in politics they still hold expectations for the state. If politicians fail those expectations they face “the loss of the silent consent and support of the unorganised masses”. In response, they “shed their apathy” and look for an outlet “to voice their new violent opposition”.

The totalitarian leader emerges from this “structureless mass of furious individuals”. With the political apathy of the masses turned to hostility, leaders will rise by breaking established norms and ignoring the way politics is usually done. Arendt dramatically says they prefer “methods which end in death rather than persuasion”. In short, they’re less likely to build politics up than they are to tear it down because that’s what the masses want.

If this all sounds depressing, there is a solution embedded in Arendt’s writing: political engagement. The masses arise when individuals are lonely and politically disconnected. They are defined by a lack of solidarity or responsibility with other citizens.

By revitalising our political community we can recreate what Arendt sees as good politics. This is when people feel a sense of personal and political responsibility for the nation and are able to band together with other citizens who have common interests. When citizens are connected in solidarity with one another, the mass never occurs and totalitarianism is held at bay.

When work defines you, unemployment is a curse

Not all Arendt’s work was concerned with war and totalitarianism. In The Human Condition, she also offers a general critique of modernity. Drawing on Karl Marx, Arendt thought the industrial age transformed humanity from thinkers into “working animals”.

She thought most people had come to define themselves by their work – reducing themselves to economic robots. Although it’s not a central point of Arendt’s analysis, this reduction is a product of the same forces she sees in the banality of evil. It’s a triumph of ‘doing’ over ‘thinking’ and of humans finding easy ways to define themselves.

Arendt wasn’t just concerned because people were reducing themselves to working drones. She also worried the industrial age which had just redefined them was also about to rob them of their new identities. She believed within a few decades, technology would replace factory jobs. Many people’s work would vanish.

“What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of labourers without labour, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.”

In a time when automation now threatens over half of jobs on average in OECD countries, Arendt’s predictions seem timely. Can we shift our identity away from work in time to survive the massive job reduction to come?

Published February 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The ethical price of political solidarity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights