Do Australian corporations have the courage to rebuild public trust?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Carl Rhodes 27 SEP 2023

Corporate Australia is having a rough time in 2023.

PwC made headlines for selling out Australian citizens by flogging details of the government’s tax avoidance schemes to potential corporate tax avoiders. Qantas has been raked over the coals for, amongst other things, lying to customers and illegally sacking workers. Elsewhere corporations are pilloried for scandalously excessive executive pay, Dickensian industrial relations standards, wilfully aggressive tax avoidance, and heartless profiteering.

Research by the market researchers at Roy Morgan recently revealed that the level of trust Australians have in corporations is at the lowest it has ever been since they started measuring it. The downward trend started with COVID but has been in free fall since the middle of 2022. Roy Morgan CEO Michelle Levine describes what is going on as the result of ‘moral blindness’ of corporations.

There is an apparent irony in play. Today’s corporations are accused of this moral blindness, while many publicly embrace ethics by taking increasingly active roles in important matters of public purpose and social impact. Corporations are weighing in on a variety of crucial political issues, such as the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, LGBTQIA+ rights, and the climate crisis.

Business as a force for good?

In the era of ‘woke capitalism’ the business world seems to feel little cognitive dissonance, let alone hypocrisy, about parading their ethical credentials in public while acting like ruthless and exploitative profiteers in the market. Being economically exploitative and socially progressive is the name of the game for many corporations.

The socially progressive position regards businesses as having the potential to be a ‘force for good’, especially by adopting progressive positions on social and environmental causes. Think of Qantas’ ‘pride flights’, PwC’s commitment to social impact, or the broad adoption of diversity and climate change initiatives by businesses of all kinds.

Many regard corporate engagement with political causes as being genuinely motivated by ethical care for their ‘stakeholders’. This view is not universal. Others see corporate activism as comprising of shallow, inauthentic and self-interested grandstanding. Between green-washing, woke-washing and virtue-signalling, corporations have been accused of using ethics to feather their own nests.

Yet others see corporate social and environmental engagement as incontrovertible evidence that CEOs have been held captive by radical left-wing activists. By this account weak-willed executives are being exploited by nefarious militants trying to use corporations as a Trojan Horse to infiltrate mainstream society.

The ‘vile maxim’ of corporate selfishness

Whichever position you might be aligned with, so-called ‘woke’ practices are in apparent contrast to the exploitative and ruthless competitive behaviours of companies like Qantas and PwC that have contributed to the demise of trust in corporations. When it comes to business, the ethical principle at play is akin to what, many years ago, economist Adam Smith condemned as the ‘vile maxim’. As he wrote in The Wealth of Nations back in 1776:

“All for ourselves and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind. As soon, therefore, as they could find a method of consuming the whole value of their rents themselves, they had no disposition to share them with any other persons.”

It is clear that many people running businesses today are enthusiastic followers of this vile maxim. To suggest this is ‘moral blindness’ can be misleading because (no matter how vile) there is an ethics at play here, and one that is widely accepted. Ayn Rand notoriously championed such an ethics as being beholden to ‘the virtue of selfishness’. By Rand’s account, pursuing self-interest is a valid, if not desirable, moral position. She stood against sacrifice as being a moral principle, instead seeing merit in “concern with one’s own interests”.

Free market capitalism was, for Rand, an ideal manifestation of her ethics. This all suggests that selfishness is not moral blindness, it is part of an ethical system that drives much business behaviour. It is also the ethics that is at the heart of Australia’s lack of confidence in the corporate world.

How to build trust

Between the twin poles of ‘woke capitalism’ and the ‘vile maxim’ we have something of a corporate identity crisis. Increasingly selfish profit-seeking in the economic sphere is matched with attestations to the pursuit of public good in the social sphere. That is not to say that all companies are vile or woke, clearly many are not. It is a fair call that enough of them are that it has led to a breakdown of public confidence in corporate Australia.

What does this all mean for how Australian corporations can build public trust? One answer is resolving their identity crisis by truly embracing and communicating the role of business in a liberal-democratic society. While businesses are responsible for returns on capital investment, that is neither their sole nor primary purpose. Neither is supporting progressive social positions without concern for the economy.

In its present condition Australian corporate capitalism is characterised by skyrocketing economic inequality, excessive executive pay, inflation fuelled by profiteering, and increasingly precarious employment. That Australian citizens do not trust corporations is an entirely rational assessment.

Corporate Australia’s challenge is to actively recognise and pursue its real social purpose. This purpose is about driving innovation and economic growth for shared prosperity, providing meaningful and secure jobs with decent pay, paying taxes that fund public services, as well as ensuring investors get a reasonable return.

Rebuilding trust is simple. What remains to be seen is which of Australia’s fallen corporations will have the courage to abandon their attachment to the vile maxim.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

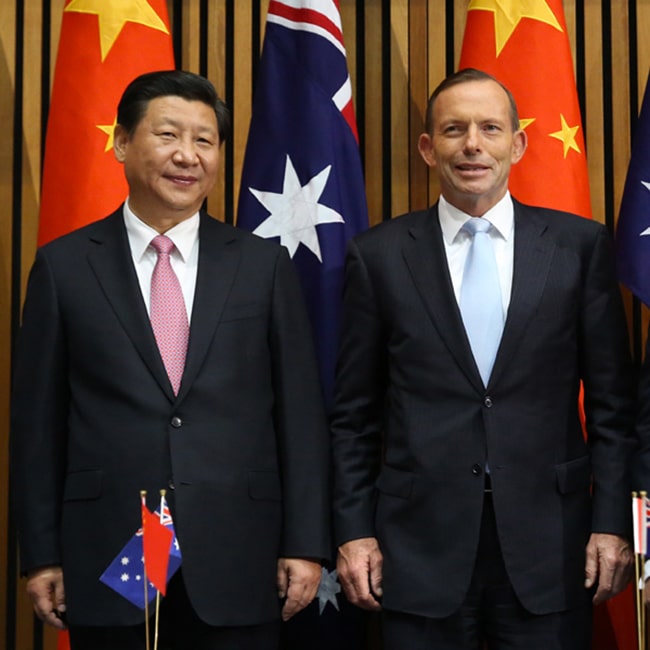

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

360° reviews days are numbered

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership