Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 30 APR 2024

Baby Reindeer, the new Netflix miniseries based on a true story, opens with a simple act of kindness — Donny Dunn (Richard Gadd), a wannabe stand-up comedian, gives a customer a free cup of tea.

“I felt sorry for her,” Donny tells us in voiceover, as Martha (Jessica Gunning) wanders into the pub where he works. It is an action he will soon regret.

The two begin conversing; as they do, Martha becomes increasingly obsessed with the comedian. Simple affection morphs into something obsessive and painful – Martha begins bombarding Donny with texts and emails. Quickly, it becomes clear: Martha is a stalker, and Donny is her victim.

That’s not exactly a new story to be told onscreen. Fatal Attraction, The Hand That Rocks The Cradle, and When A Stranger Calls have all dealt with the significant fear and anxiety that being stalked can create – when you’re the victim of a stalker, you live on a constant knife’s edge, forever expecting the next email, the next escalation. These films capture that tension.

But what Baby Reindeer does additionally is depict – in a surprisingly complex way – the blend of emotions a victim can feel towards their stalker, not all of them strictly negative. And more than that, it explores the difficult histories that can make a stalking victim vulnerable to being harassed in the first place.

Which is why it is fascinating – and troubling – that such a complicated, nuanced show has led some viewers to begin replicating Martha’s behaviour to find the real people behind the story.

The complexity of the stalker/victim relationship

Stalking is, as philosopher Elizabeth Brake notes, composed of actions “which would normally be permissible; indeed, many stalking behaviors are protected liberties.” That makes it a complicated form of ethical wrong, one many stalkers take advantage of. There’s nothing bad about sending an email. There’s not even anything wrong with sending many emails – under specific circumstances. What makes stalking terrifying is the amount of communication, and, often, its intent.

Additionally, some stalkers are themselves dealing with trauma, or have been victims of a serious harm. This is what Baby Reindeer captures – Martha is harming Donny, but she herself has been harmed. More than that, Donny’s traumatic past – he is the victim of sexual assault – makes him open to her affection initially. These are two people who have suffered, and are continuing to suffer. They find each other, amidst the chaos of traumatic flashbacks, and a deep sense of purposelessness.

Perhaps if things were different, they might have become friends. After all, they are not so dissimilar, in some ways: Baby Reindeer ends with Donny finding himself in the exact position Martha was in when he first encountered her, relying on the random kindness of a bartender.

In this way, Baby Reindeer does not condemn Martha. Nor does it condemn Donny, even though they have both made mistakes. Instead, it sees their actions as deeply tied to past harms, a continuation of the cycle of abuse.

And a cycle that some viewers of the show are perpetuating.

Viewer as stalker

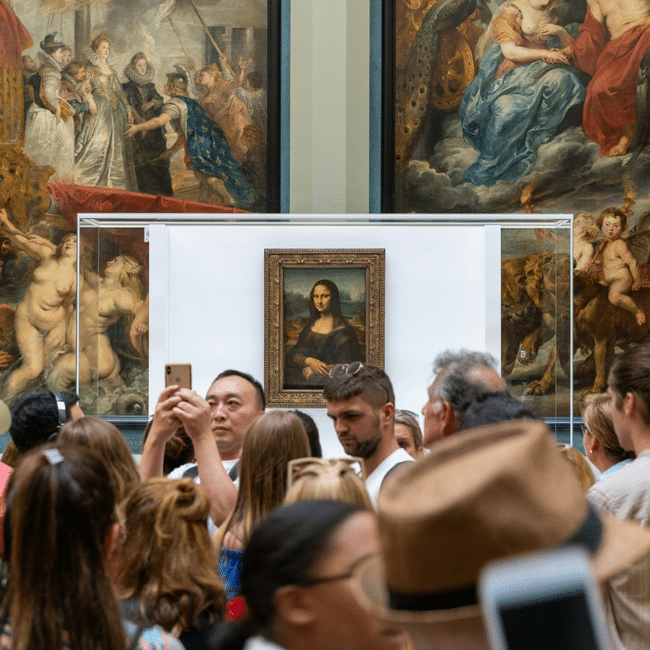

Since Baby Reindeer became a smash hit, some viewers have begun attempting to track down the real humans that inspired the show. As The Guardian notes, “online sleuths” (those are the article’s words), believe they’ve found the real-life Martha. But so obsessive and dangerous has been the search, that innocent people have been caught up in the fray – one man was mistakenly believed to be the television writer who assaulted Donny, and received death threats as a result.

But whether or not the “right” targets have been uncovered and attacked, such a response to the show is deeply unethical. Baby Reindeer itself doesn’t want to demonise Martha – so why are some viewers doing that themselves? Baby Reindeer is a cautionary story about letting passion overcome reason, and trying to track down people who don’t want to be tracked down. That stalking is being perpetuated in its name is a deep ethical wrong.

It’s also a common ethical issue in our modern age. Increasingly, online vigilantes – better to call them that than “sleuths” – have come to behave in a way that shows they believe under certain circumstances, normal ethical rules are waved away. Think of the targeted harassment that was directed towards the real people that stans assumed Ariana Grande’s or Taylor Swift’s new records were about. Or Beyonce’s ‘Beyhive’ hounding a women off social media. In all of these cases, the abuse was “justified” in the mind of the perpetrators. They believed an ethical crime had been committed, and so gave themselves free rein to punish right back.

So it goes in the case of Baby Reindeer. Martha wronged Donny; the TV writer assaulted him. In an increasingly punitive, carceral and old-school digital world, viewers are taking it on themselves to dole out their own justice, in order to reset wrongs.

In actual fact, they are not moral arbiters. They are committing a wrong themselves. And it is a wrong that we must call out.

Baby Reindeer urges us to consider human beings as complex – not deserving of punishment, but of understanding, even if we condemn their actions.

We can want someone to be far away from us, given the harms they have committed. But we must attempt to collectively return to a place where retributive justice – so often confused as “activism” – does not cloud our understanding of complexity. After all, as that final scene of Baby Reindeer shows, we could all find ourselves in Martha’s shoes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 APR 2024

Shock reverberated throughout Australia at the news of a frenzied knife attack in Sydney at Westfield Bondi Junction on 13 April — an attack that claimed the lives of six people and injured many more.

Naturally, such an event triggers a surge of news reporting and social media posts. But the news and social media conversation quickly pivoted from reporting the facts of the event to seeking answers. How could such a horrifying thing happen? What could drive someone to do something like this? Could it happen again? Could it happen near me? Am I safe?

Our minds naturally recoil from violence. But they recoil just as much from the prospect that violence can be random or senseless. We have a deep and abiding need to make sense of such horrors, to place them within a causal narrative that can help us understand how they fit in to the world around us. But in our search for a narrative, we can easily latch on to something convenient, whether or not it’s true.

Violence in search of a reason

For many people — particularly those on social media — the first narrative they turned to was terrorism. It’s not that they necessarily wanted it to be an act of terrorism. But terrorism is something that we all, sadly, understand only too well. By labelling the attack as “terrorism”, the attack ceases being random and becomes part of a system we can comprehend.

So, many people may have felt a slight sense of unease when the New South Wales police commissioner declared that it was not an act of terrorism. If not terrorism, what was it? What could possibly motivate such a horrific attack?

Then it emerged that the attacker targeted more women than men. So perhaps it was misogyny that motivated him? Perhaps he was one of these “incels” (or involuntary celibates) we sometimes hear about? But again, the details were unclear, so the speculation continued.

When the attacker’s mental health issues were revealed, that offered another way to make sense of the violence. People could draw on a well-known narrative of a broader mental health crisis across the nation. And while that might inspire greater attention and investment in mental health, it can also instil fear and suspicion of those who experience a range of conditions but pose no threat to the public, possibly leading to increased stigma or disadvantage.

And, of course, there’s the fact the attacker used a knife, which will inevitably lead to a conversation about whether we ought to regulate the sale of knives, even if that might hamper legitimate use and have done little to prevent this attack.

How to live with the uncertainty

Yet we must remember that it remains a distinct possibility this was a freak event, one that doesn’t fit into any clear causal narrative, and one that doesn’t tell us anything meaningful about whether such horrific attacks are likely to occur again in the future. It might be the case that there was little or nothing that could have been done to prevent it. Ultimately, it might just be a random and senseless act of violence, no matter how much our minds recoil from such a possibility.

It’s natural for us to seek meaning when we’re faced with apparently senseless violence, even if it can cause us to jump to conclusions or latch on to hasty solutions. What’s less natural is sitting with the uncertainty that comes with not knowing how or why this happened.

So, what to do?

First, we should forgive ourselves (and everybody else) for being human, and desperately wanting to live in a safe and predictable world. But second, we need to acknowledge that safety and predictability are often outside of our control. Even so, it doesn’t mean we are powerless. As the Stoics pointed out, we can still choose how to encounter the world, and likewise, which narratives to adopt to make sense of it.

Instead of focusing on the motivations of the attacker, which might always remain elusive, we can look to other parts of the picture, including those that reinforce our appreciation of our fellow humanity, even in the face of unspeakable tragedy. We can focus on the acts of heroism by individuals to hold back the attacker. Or on the bravery of the police officer who confronted him. Or the workers who hastened to protect the customers in their stores. Or the outpouring of support from the community to the victims and their families.

There is a strong narrative here, one that can boost our empathy for others and buttress us against tragedy, whether deliberate or random. But it might require us to allow some questions to go unanswered.

This article was originally published in ABC Religion and Ethics.

Image by Richard Milnes / Alamy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What are we afraid of? Horror movies and our collective fears

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

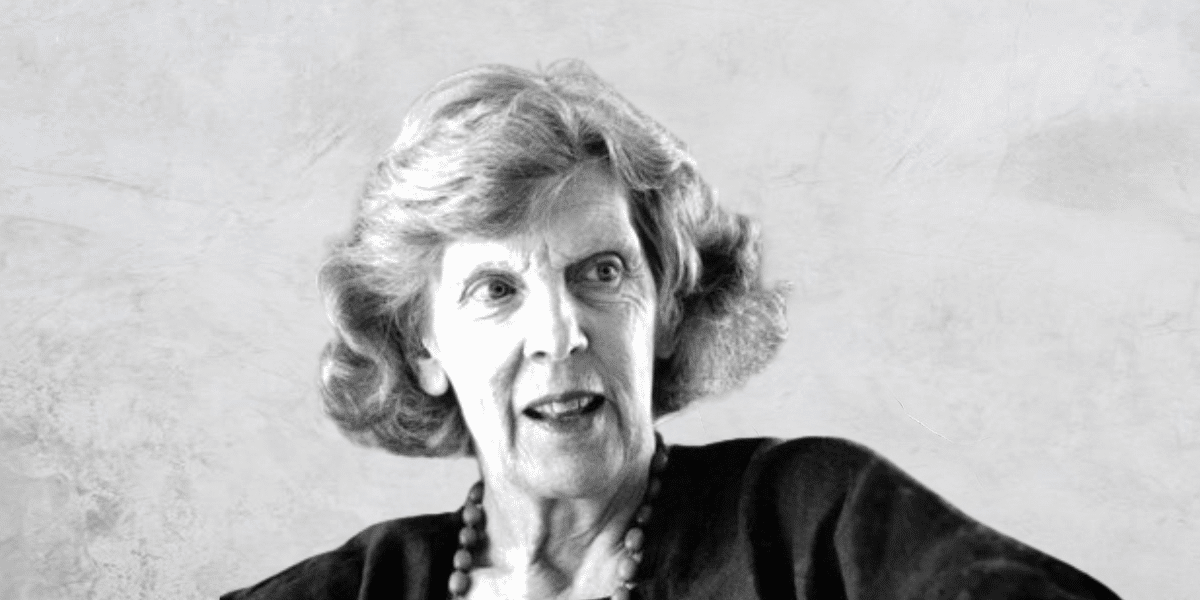

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Philippa Foot (1920-2010) is one of the founders of contemporary virtue ethics, reviving the dominant Aristotelian ethics in the 20th century. She introduced a genre of decision problems in philosophy as part of the analysis in debates around abortion and the doctrine of double effect.

Philippa Foot was born in England in 1920. While receiving no formal education throughout her childhood, she obtained a place at Somerville College, one of the two women’s colleges at Oxford. After receiving a degree in 1942 in politics, philosophy and economics, she briefly worked as an economist for the British Government. Besides this, she spent her life at Oxford as a lecturer, tutor, and fellow, interspersed with visiting professorships to various American colleges, including Cornell, MIT, City University of New York and University of California Los Angeles.

Virtue ethics

In the philosophical world, Philippa Foot is best known for her work repopularising virtue ethics in the 20th century. Virtue ethics defines good actions as ones that embody virtuous character traits, like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. This is distinct from deontological ethical theories which encourage us to think about the action itself and its consequences or purpose instead of the kind of person who is doing the action.

“What I believe is that there are a whole set of concepts that apply to living things and only to living things, considered in their own right. These would include, for instance, function, welfare, flourishing, interests, the good of something. And I think that all these concepts are a cluster. They belong together.”

The doctrine of double effect

Imagine you are the driver of a runaway trolley that is barrelling down the tracks. You have the option to do nothing, and let five people die, or the option to switch the tracks and kill one person.

This is Philippa Foot’s famous trolley problem. This thought experiment encourages us to think about the moral differences between actively causing death (e.g. pulling a lever to get the trolley to change tracks) and passively or indirectly causing death (doing nothing, allowing the trolley to kill five people). Utilitarians might argue that five deaths is far less desirable than one death, but many people instinctively feel that actively causing a death has a different moral weight than doing nothing.

Perhaps Foot’s most influential paper is The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect, published in 1967. Here, she explains what is called the Doctrine of the Double Effect, which explains why some very bad actions (like killing) might be permissible because of their potentially positive outcomes. The trolley problem is one example of the doctrine of double effect, but she also uses various other cases.

“The words “double effect” refer to the two effects that an action may produce: the one aimed at, and the one foreseen but in no way desired. By “the doctrine of the double effect” I mean the thesis that it is sometimes permissible to bring about by oblique intention what one may not directly intend.”

For example, what if one person needed a large dose of a rare medicine to save their life, but that same amount of medicine could save the lives of five others who each needed less? Would we think that the “oblique intention” of a nurse who administers the medicine to one person instead of the five people is justified?

Foot finds that it would be wise to save the five people by giving them each a one-fifth dose of the medicine. However, she encourages us to interrogate why this feels different from the organ donor case, where we save five people who need organ transplants by sacrificing one person.

“My conclusion is that the distinction between direct and oblique intention plays only a quite subsidiary role in determining what we say in these cases, while the distinction between avoiding injury and bringing aid is very important indeed.”

When the trolley problem is taken to its logical conclusion, these fallacies become even more obvious. As John Hacker-Wright writes, the trolley problem “raises the question of why it seems permissible to steer a trolley aimed at five people toward one person while it seems impermissible to do something such as killing one healthy man to use his organs to save five people who will otherwise die.”

Foot has also contributed to moral philosophy with her writing on determinism and free will, reasons for action, goodness and choice, and discussions of moral beliefs and moral arguments.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

True crime media: An ethical dilemma

In the realm of media and entertainment, the insatiable public appetite for gripping, real-life narratives has propelled the rise of one particular genre; true crime.

From podcasts and movies to videos on YouTube and TikTok, the last decade has witnessed unparalleled demand for crime stories. However, this surge prompts questions regarding the ethical issues inherent in true crime. By condemning the transgression of principles, the romanticised portrayal of perpetrators, and the dramatisation of suffering perpetuated by content creators, we can advocate for transformative legislation to harness the positive potential of the genre.

A glaring ethical issue present in true crime is the violation of consent and privacy of victims and families. Currently, media companies and influencers don’t require their consent when publishing content. The names, ages, backgrounds, and family details of victims are often laid bare for public consumption. This is overwhelming for victims and families, as their most painful and intimate experiences are shared with the world without their permission.

Additionally, these vulnerable stakeholders are subjected to online scrutiny, where netizens give unsolicited opinions and commentary. This reopens the scars left by the ordeals, as exemplified by Netflix’s recent docuseries Monster – Jeffrey Dahmer (2022). The families of Dahmer’s victims were not even informed of the production. Eric Perry, cousin of victim Errol Lindsey, tweeted, “it’s re-traumatising over and over again, and for what?”.

While some argue that the sympathy generated from productions could help families heal, it is imperative to recognise that individuals process sympathy in different ways. Even if sympathy comes from a well-meaning place, if it is uninvited, it may cause feelings of exposure and stress. Therefore, consent must be mandated to end the unethical violation of principles for monetary gain.

Another pressing ethical concern is the romanticised portrayal of perpetrators for increased viewership. Humans, in having adrenaline-craving brains and an inherent fascination with tragedy, are naturally attracted to crime.

Casting conventionally attractive actors to play serial killers, for example Zac Efron as Ted Bundy in Netflix’s 2019 film Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, exacerbates this attraction to a dangerous level. This promotes the toxic fan culture surrounding criminals on media platforms, portraying them as brooding, romantic ‘bad boys’. It gives perpetrators the spotlight and awe, whilst victims are shunned into the shadows.

The real-life consequences of romanticisation were seen in Cameron Herrin’s vehicular homicide case. Due to his physically attractive appearance, netizens on TikTok and Twitter rallied for sentence reduction through the #JusticeForCameron trend. However, this mostly contained irrelevant videos, such as fan edits of his face and highlight reels of his ‘hottest moments in court’, where netizens dubbed him “too cute to go to jail”. A ‘change.org’ petition for sentence reduction was created by fans and signed over 28,000 times, demonstrating how the romanticisation of killers in media has influenced the public to condone the actions of attractive criminals.

This was further confirmed by a 2010 Cornell University study, revealing, “in criminal cases, better-looking defendants receive lower sentences”. Hence, we must hold media producers accountable for romanticised content to stop glorifying the legacies of killers and trivialising their heinous crimes. As consumers, we must remain vigilant and conscious in remembering the monster behind the dazzling smile; a cold-blooded killer.

Furthermore, another ethical dilemma in true crime is the dramatisation of narratives for audience retention. True crime has surged in popularity recently, with a 60% increase in consumption in the US from 2020-2021. This was achieved through insensitive and exaggerated portrayals of people and events to create a ‘juicier’ story, exploiting the victims’ suffering and trauma for entertainment.

As exemplified by the true crime podcast Rotten Mango, content creators often create fictional characterisations of the people involved in the stories for their drama-hungry consumers. They fabricate victims’ thoughts and emotions during the ordeal based on their personal assumptions, which is insensitive to the memory of the victims. In response to Netflix’s Dahmer docuseries, Rita Isbell, sister of a victim, expressed her wish for Netflix to provide tangible benefits such as money to victims’ families. She stated, “if the show benefitted [the victims] in some way, it wouldn’t feel so harsh and careless.” Hence, the dramatisation of crime narratives for entertainment purposes must be restricted, and fictional fabrications of the ordeals banned.

The presently unethical and insensitive genre of true crime demands key changes to harness its positive potential.

We must implement legislation that mandates consent, holds media producers accountable for romanticised content, and restricts dramatisation of narratives.

This will transform the genre into a positive force that empowers those who have endured similar experiences, condemns perpetrators, provides support and closure to victims’ loved ones, and genuinely commemorates victims. By implementing these changes, true crime will evolve into an ethical and empathetic form of media that positively impacts our society.

‘True crime media: An ethical dilemma‘ by Jessica Liu is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The art of appropriation

BY Jessica Liu

Jessica Liu (15) is currently attending Abbotsleigh Senior School. At school, she enjoys humanities, maths, and French. Her hobbies include piano, debating and basketball.

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Zoe Timimi 3 APR 2024

We’re living through brutal and devastating times.

Apocalyptic scenes of mass bloodshed are being live-streamed to our phones by journalists who have millions of followers. Awareness of colonial brutality and conflict across the globe has permeated the minds of the Western social media generation on an unprecedented scale, as well as our government’s complicity in it.

Yet life goes on in Australia and across the West. Every week, thousands march through the Sydney CBD to protest genocidal violence in Palestine. We gather in Hyde Park where Palestinians tell us of the destruction of their families and homes, and then we march, passing queues spilling out of high-end shops and chanting ‘while you’re shopping, bombs are dropping’.

It feels as if I’m seeing the individualism that defines our consumer culture with fresh eyes. It’s always been there in plain sight, but suddenly I marvel at how obvious its function is, how it keeps us busy looking in the wrong direction by selling us an alluring dream.

The difference between our everyday and theirs is hard to comprehend. Increasingly I find myself consumed by these overwhelming contradictions; grief at the hands of terror states and the need to keep living in our society of supposed positivity.

I’m questioning how much of my time and energy is wrapped up in searching for the dream-like abundance and pleasure that modern capitalism promises me, unpicking everything I thought I knew about what I wanted from life. How can you feel pleasure in the face of horror?

Consumer culture paints a vision of the good life that’s full of pleasure, relaxation and joy. Influencers sell us manicured images of sun, sea and luxury food, showing us what a free and fulfilled life looks like. But unreachable for many, we often end up seeking consolation in smaller consumer pleasures, distracting ourselves with whatever repetitive hits of relief we can find after we finish our days at work. Dreams of abundance keep people sustained in oppressive systems, searching for a sparkling life that never arrives for most of us.

Dissatisfaction with this cycle of unfulfilling work and empty pleasure seeking has long simmered under the surface. But the lid is now off. The way meaning has been drained from our visions of the good life is brought into focus by brave journalists demanding we confront ugly truths. The daily effort to find pleasure, however small – the morning coffee, the new clothes, the office pizza parties, suddenly pale in significance to the scale and urgency of the problems that face us; the rot at the heart of our system has revealed itself. Discontent has turned to rage. Others feel it too – millions across the globe have been protesting for months on end, refusing to stay silent.

Philosopher and writer Mark Fisher wrote about the emptiness he observed in how his students experienced pleasure. He thought that despite the abundance of instantly pleasurable activities they engaged in, there was still a widespread sense that something was missing from life. He argued that just because we have an abundance of pleasure accessible instantly, it doesn’t mean that life is actually more pleasurable. In fact, he thought the opposite was true.

“Depression is usually characterized as a state of anhedonia, but the condition I’m referring to is constituted not by an inability to get pleasure so much as it is by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure.”

He’s not the only one to observe a widespread emotional decay brought on by the constant consumption of quick fix, disembodied pleasure. Kate Soper, in her book Post Growth Living, argues that we must dissociate pleasure and our vision of the good life from the culture of consumerism that so often promotes mindless and toxic pleasure seeking. Like Fisher, she points out how a seductive vision of comfort and abundance so often results in a sterile search for contentment that never comes. She argues that we urgently need to redefine our idea of the good life, asking us to imagine how collective life could transform if we placed care and ethics at the center of our priorities rather than consumer driven gratification.

What both of these writers pick up on is how meaning has been drained from life under Western capitalism, and how pleasure is so often used to plaster over deeply felt doom for the future. They both remind us that sustaining and rich fulfilment does not come from instant gratification.

I think many of us intuitively see that the most pleasurable things we can do with our lives are immaterial, found in the substance of considered, caring and meaningful relationships. What’s a much bigger task is to translate this into finding the pleasure in fighting for bigger social causes. To recognise that a good life must be built on an ethics of justice.

It’s about more than just making different consumer choices, about taking a few hours to go to a march instead of shopping. It’s about finding a set of values that you believe in, and acting in accordance with them, holding yourself and others accountable to the best of your ability with the time and resources you have. Acting with political principle is hard in a society that does everything it can to tempt you into hopelessness, but there is a growing appetite for it. In the face of unthinkable violence, so many have been searching for meaning bigger than the endless cycles of work and shopping.

We first need to recognise that if we want to build any meaningful future for ourselves, we can’t turn away from the dehumanisation of others. The good life isn’t built on collective denial of blistering injustice – burying our heads in the fake comforts of consumerism offers us a bleak future. Our own search for meaning brings us towards our interconnected struggle: Palestine and other occupied nations call for us to fight for justice – our ability to live good lives depends on that justice as well as theirs.

bell hooks said that there can be no love without justice. I think the same can be said for pleasure.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre Nominated for a UNAA Media Peace Award

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

BY Zoe Timimi

Zoe is passionate about all things mental health, community and relationships. She holds a BA in Sociology and an MA International Political Economy, but has spent the last few years working as a freelancer in various TV development and writing roles.

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Flushed cheeks, lowered gaze and an interminable voice in your head criticising your very being.

Imagine you’re invited to two different events by different friends. You decide to go to one over the other, but instead of telling your friend the truth, you pretend you’re sick. At first, you might be struck with a bit of guilt for lying to your friend. Then, afterwards, they see photos of you from the other event and confront you about it.

In situations like this, something other than guilt might creep in. You might start to think it’s more than just a mistake; that this lie is a symptom of a larger problem: that you’re a bad, disrespectful person who doesn’t deserve to be invited to these things in the first place. This is the moral emotion of shame.

Guilt says, “I did something bad”, while shame whispers, “I am bad”.

Shame is a complicated emotion. It’s most often characterised by feelings of inadequacy, humiliation and self-consciousness in relation to ourselves, others or social and cultural standards, sometimes resulting in a sense of exposure or vulnerability, although many philosophers disagree about which of these are necessary aspects of shame.

One approach to understanding shame is through the lens of self-evaluation, which says that shame arises from a discrepancy between self-perception and societal norms or personal standards. According to this view, shame emerges when we perceive ourselves as falling short of our own expectations or the expectations of others – though it’s unclear to what extent internal expectations can be separated from social expectations or the process of socialisation.

Other approaches lean more heavily on our appraisal of social expectations and our perception of how we are viewed by others, even imaginary others. These approaches focus on the arguably unavoidably interpersonal nature of shame, viewing it as a response to social rejection or disapproval.

This social aspect is such a strong part of shame that it can persist even when we’re alone. One way to exemplify this is to draw similarity between shame and embarrassment. Imagine you’re on an empty street and you trip over, sprawling onto the path. If you’re not immediately overcome with annoyance or rage, you’ll probably be embarrassed.

But there’s no one around to see you, so why?

Similarly, taking the example we began with, imagine instead that no one ever found out that you lied about being sick. It’s possible you might still feel ashamed.

In both of these cases, you’re usually reacting to an imagined audience – you might be momentarily imagining what it would feel like if someone had witnessed what you did, or you might have a moment of viewing yourself from the outside, a second of heightened self-awareness.

Many philosophers who take this social position also see shame as a means of social control – notably among them is Martha Nussbaum, known for her academic career highlighting the importance of emotions in philosophy and life.

Nussbaum argues that shame is very often ‘normatively distorted’, in that because shame is reactive to social norms, we often end up internalising societal prejudices or unjust beliefs, leading to a sense of shame about ourselves that should not be a source of shame. For example, people often feel ashamed of their race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability due to societal stigma and discrimination.

Where shame can go wrong

The idea of shame as a prohibitive and often unjust feeling is a sentiment shared by many who work with domestic violence and sexual assault survivors, who note that this distortive nature of shame is what prevents many women from coming forward with a report.

Even in cases where shame seems to be an appropriate response, it often still causes damage. At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas session in 2022, World Without Rape, panellist and journalist Jess Hill described an advertisement she once saw:

“…a group of male friends call out their mate who was talking to his wife aggressively on the phone. The way in which they called him out came from a place of shame, and then the men went back to having their beers like nothing happened.” Hill encourages us to think: where will the man in the ad take his shame with him at the end of the night? It will likely go home with him, perpetuating a cycle of violence.

Likewise, co-panellist and historian Joanna Bourke noted something similar: “rapists have extremely high levels of abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame”. Neither of these situations seem ‘normatively distorted’ in Nussbaum’s sense, and yet they still seem to go wrong. Bourke and other panellists suggested that what is happening here is not necessarily a failing of shame, but a failing of the social processes surrounding it.

Shame opens us to vulnerability, but to sit with vulnerability and reflect requires us to be open to very difficult conversations.

If the social framework for these conversations isn’t set up, we end up with unjust shame or just shame that, unsupported, still manifests itself ultimately in further destruction.

However, this nuance is far from intuitive. While people are saddened by the idea of victims feeling shame, they often feel righteous in their assertions that perpetrators of crimes or transgressors of socials norms should feel shame, and that their lack of shame is something that causes the shameful behaviour in the first place.

Shame certainly has potential to be a force for good if it reminds us of moral standards, or in trying to avoid it we are motivated to abide by moral standards, but it’s important to retain a level of awareness that shame alone is often not enough to define and maintain the ethical playing field.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Ruby Hamad 25 MAR 2024

Increasingly, it appears that constructive criticism and cynical attacks are being conflated. And perhaps it’s nowhere more apparent or more troubling than when it comes to criticism of the news media.

In 1993, Edward Said stunned the world of cultural criticism with his revolutionary critique of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. The literary professor and avowed lover of the Western literary canon reviewed Austen in a way like never before: as a cultural artefact that reflected and embodied the British imperial ethos.

Austen, he wrote, “synchronises domestic with international authority, making it plain that the values associated with such higher things as ordination, law, and propriety must be grounded in actual rule over and possession of territory.”

As both a critic and a fan, Said was surprised at accusations he was discrediting Austen. Rather, he was demonstrating that even novels ostensibly about domesticity could not be separated from the politics of the time.

Said showed that art not only can but must be both enjoyed and critiqued.

That criticism must, in other words, be constructive.

Said’s approach to criticism is more needed now than ever. Increasingly, it appears that constructive criticism and cynical attacks are being conflated.

I find this nowhere more apparent or more troubling than when it comes to criticism of the news media.

After The New York Times opened an Australian bureau several years ago, some readers and journalists complained its coverage was patronising. Such complaints, journalist and former Times contributor Christine Keneally said, indicated that locals felt it “considered itself superior to the local press”.

As I wrote at the time, “grievances included needlessly explaining Australia to Australians, engaging in parachute journalism, and not employing enough local journalists.” The newspaper wasn’t doing anything that Australian journalists don’t do as a matter of routine when covering foreign places. Whether wittingly or unwittingly, English-language media often assume an air of authority as they “explain” the local culture and events to their audience back home, adopting an almost anthropological tone that has been frequently and hilariously satirised.

The problem, then, was not the Times per se but Western approaches to journalistic “objectivity” that equate their own interpretations with fact.

Consequently, the criticism centred on mocking the Times rather than interrogating the broader problem of Western journalistic processes and assumptions. This merely served to make the Times defensive and resistant to the criticism.

It is futile to simply demand that journalists “do better” on certain issues or to single out specific publications when the problem so often comes down to Western media conventions as a whole.

How then should we go about it? Robust public constructive criticism of the press is vital. Not least because:

“There is everywhere a growing disillusionment about the press, a growing sense of being baffled and misled; and wise publishers will not pooh-pooh these omens.”

This quote could easily have been written last week but comes from legendary American editor Walter Lippmann in his 1919 essay ‘Liberty and the News’.

Lippmann urged fellow journalists not to reject criticism but use it as a means to improve. “We shall advance when we have learned humility,” he predicted hopefully. “When we have learned to seek truth, to reveal it and publish it; when we care more for that than for the privilege of arguing about ideas in a fog of uncertainty.”

Some of this antipathy towards critique could perhaps be explained by a lack of consensus of what critique actually is. The job of a critic is often misrepresented as being merely “to criticise”, telling us what is good and bad. However, the true role of a critic, explains culture writer Emily St. James, is “to pull apart the work, to delve into the marrow of it, to figure out what it is trying to say about our society and ourselves”.

Social media complicates our understanding further because of the difficulty of in reading people’s tone and intent online. Then there is also the unfortunate fact that social media is so often used deliberately as a platform to launch cynical, shaming attacks, which makes it even more challenging to distinguish criticism from cynicism.

This can be applied to the news media as easily as it can to novels or films.

As media scholar James W Carey observed, and as Said demonstrated in his critique of Austen, genuine criticism is not a “mark of failure or irrelevance, it is the sign of vigour and importance”.

Over many decades historians and scholars have agreed on the shape criticism should take. Namely, that criticism is an ongoing process of exchange and debate between the news media and its audience. That it should be grounded in knowledge rather than solely in emotion. That it should not be pedantic, petty, and shaming.

Media researcher Wendy Wyatt defined it simply as “the critical yet noncynical act of judging the merits of the news media”.

And as media scholar James W Carey observed – and Said demonstrated with Austen – genuine criticism is not a “mark of failure or irrelevance, it is the sign of vigour and importance”.

Lippmann and Wyatt advocated for criticism of the press by the press, such as a public editor or ombudsman hired by the publication solely to address readers’ concerns and complaints.

Others including Carey argued that true criticism can come only from the outside; from academics or authors that are not on the payroll to ensure fairness, and minimises the possibility of retribution. Many journalists, they warn, have been ostracised by their peers for daring to critique their own.

Much of the onus, then, falls to editors and publishers to open up the news media to constructive criticism, and to not “pooh-pooh” our concerns. But we, as individuals and as a society, all bear some responsibility for fostering a social climate that encourages such critique.

If we are to demand that journalists heed our criticism, we must also enter into it in good faith. Like journalism itself, any and all criticism should also be weighed up on its merits. Our ultimate goal should not be merely to shame journalists but to transform the news media in an ongoing process of reform and improvement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Arguments around “queerbaiting” show we have to believe in the private self again

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Gender quotas for festival line-ups: equality or tokenism?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

BY Ruby Hamad

Ruby Hamad is a journalist, author and academic. Her nonfiction book White Tears/Brown Scars traces the role that gender and feminism have played in the development of Western power structures. Ruby spent five years as a columnist for Fairfax media’s flagship feminist portal Daily Life. Her columns, analysis, cultural criticism, and essays have also featured in Australian publications The Saturday Paper, Meanjin, Crikey and Eureka St, and internationally in The Guardian, Prospect Magazine, The New York Times, and Gen Medium.

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff Major General Paul Symon Dr Miah Hammond-Errey 19 MAR 2024

Better ethical approaches for individuals, businesses and organisations doesn’t just make moral sense. The financial benefits are massive, too.

It might seem a little ironic to take ethics advice from an intelligence agency that consciously deploys deception, yet it shows why access to ethical advice is vitally important. Indeed, we argue that the example of an ethics counsellor within ASIS demonstrates why every organisation should have (access to) an ethical adviser.

Ethics is often considered to be a personal or private activity, in which an individual makes decisions guided by an ethical code, compass or frame of reference. However, emerging technologies necessitate consideration of how ethics apply “at scale”.

Whether we are conscious of this (or not), ethical decisions are being made at the “back end” – or programming phase – but may not be visible until an outcome or decision, or user action, is reached at the other end of the process.

Miah Hammond-Errey describes in her book, Big Data, Emerging Technologies and Intelligence: National Security Disrupted, how “ethics at scale” is being driven by algorithms that seek to replicate human decision-making processes.

This includes unavoidable ethical dimensions, at increasing levels of speed, scope and depth – often in real time.

The concept of ethics at scale means that the context and culture of the companies and countries that created each algorithm, and the data they were trained on, increasingly shapes decisions at an individual, organisation and nation-state level.

Emerging technologies are likely to be integrated into work practices in response to the world itself becoming more complex. Yet, those same technologies may themselves make the ethical landscape even more complex and uncertain.

The three co-authors recently discussed the nexus of ethics, technology and intelligence, concluding there are three essential elements that must be acknowledged.

First, ethics matter. They are not an optional extra. They are not something to be “bolted on” to existing decision-making processes. Ethics matter: for our own personal sense of peace, to maximise the utility of new technologies, for social cohesion and its contribution to national security and as an expression of the values and principles we seek to uphold as a liberal democracy.

Second, there is a strong economic case for investing in the ethical infrastructure that underpins trust in and the legitimacy of our public and private national intuitions. A 10 per cent improvement in ethics in Australia is estimated to lead to an increase in the nation’s GDP of $45 billion per annum. This research also shows improving the ethical reputation of a business can lead to a 7 per cent increase in return on investment. A 10 per cent improvement in ethical behaviour is linked with a 2.7 to 6.6 per cent increase in wages.

Third, ethical challenges are only going to increase in depth, frequency and complexity as we integrate emerging technologies into our existing social, business and government structures. Examples of areas already presenting ethical risk include: using AI to summarise submissions to government, using algorithms to vary pricing for access to services for different customer segments or perhaps using new technologies to identify indicators of terrorist activity. That’s before we even get to novel applications employing neurotechnology such as brain computer interfaces.

Ethical challenges are, of course, not new. Current examples driven by new and emerging technologies include privacy intrusion, data access, ownership and use, increasing inequality and the impact of cyber physical systems.

However, an extant need for ethical rumination is, for now at least, a human endeavour.

As a senior leader of ASIS, with a background in the military, Major General Paul Symon (retd) strongly supported resourcing a (part-time) ethics counsellor. He was aware the act of cultivating agents, and the tradecraft involved, would inevitably demand moral enquiry by the most accomplished ASIS officers.

His belief was without a solid understanding of ethics, there was no standard against which the actions of the profession, or the choices of individuals, could be measured.

So, a relationship emerged with the Ethics Centre. A compact of sorts. Any officer facing an ethical dilemma was encouraged to speak confidentially to the ethics counsellor. The conversation and the moral reasoning were important.

General Symon guaranteed no career detriment to anyone who “opted out” of an activity so long as they had fleshed out their concerns with the ethics counsellor. Often, an officer’s concerns were allayed following discussion, and they proceeded with an activity knowing there was a justification both legally and ethically.

Perhaps if we’d had ethical advisers available across other institutions, we might have prevented some of the greatest moral failures of recent times, such as the pink batts deaths and robodebt.

If we had ethical advisers accessible to industry, then perhaps we’d have avoided the kind of misconduct revealed in multiple royal commissions looking into everything from banking and finance to the treatment of veterans to aged care.

We believe our work over years, including examples in defence and intelligence, demonstrates practical examples and the requirement to build our national capacity for ethical decision-making supported by sound, disinterested advice. That is one reason we support the establishment of an Australian Institute for Applied Ethics with the independence and reach needed to work with others in lifting our national capacity in this area.

Pledge your support for an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics. Sign your name at: https://ethicsinstitute.au/

This article was originally published in The Canberra Times.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Am I falling behind in life “milestones”?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY Major General Paul Symon

Major General Paul Symon (retd) is a former director-general of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.

I changed my mind about prisons

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Sophie Yu 14 MAR 2024

Every time the face of a criminal flashed up on the screen of our flatscreen TV, my parents would never hesitate to condemn the perpetrator, and demand the prolonged imprisonment of the thief or shoplifter.

For violent crimes, the death penalty would often come into conversation.

My siblings and I, perched on the leather couch, would listen open-mouthed, our young minds unable to comprehend how anyone would even consider such an act. I thought to myself: anyone who went to jail was inherently evil, different to normal people.

Yet, as I grew older and started to reach beyond the sheltered confines of our upper-middle-class home, that perspective gradually fell apart.

I have come to realise that our prison system is dysfunctional, a warped interpretation of right and wrong. A system designed for retribution, that essentially calls an end to a person’s potential in life, is both ethically and practically malfunctioning. Intended to benefit society through rightful punishment and restorative justice, it is instead one of the largest perpetrators of discrimination and often even worsens a prisoner’s life after release.

For instance, consider the story of Wesley Ford: a gay Whadjuk/Ballardong man, who battled with a drug addiction that fuelled 13 prison stints over two decades. He was just one of the 60% of Australian prison detainees who have been previously incarcerated. We have one of the highest recidivism rates in the world and, in a world where over half of prisoners expect to be homeless after release, and it is nearly impossible to secure employment, is that really such a surprise?

Our sentences do not tend to be harsh enough to fully realise the power of deterrence, nor are the quality or quantity of support services anywhere near sufficient to rehabilitate offenders.

In the words of Ford, ‘There were services there, but it is such a farce, because … they are so few and far between hardly anyone can get onto them.’

This also promotes a cycle of crime, further disadvantaging minority groups. Despite making up only 2% of the overall population, Indigenous Australians constitute nearly 30% of prisoners. They are twice as likely to have been refused bail by police before their first court appearance.

As for a solution, the harsher approach, employed by regimes such as Russia, is evidently unethical. Criminal behaviour must be punished, but the unnecessary imposition of prolonged sentences or even death penalties for minor offenders is closer to a violation of basic human rights, rather than the intended enforcement of justice. This is supported by various ethical frameworks, be it a utilitarian goal to preserve life, or the Christian belief in grace. Instead, especially for those who are low-risk offenders, restorative justice measures should be utilised to punish behaviour whilst also incentivising criminals to make better decisions. This approach has been proven to work, as evidenced by the Norwegian system.

With a system of small, community facilities that focus on rehabilitation and reintegration into society, Norway’s prison system ensures that prisoners do not lose their humanity and dignity whilst incarcerated. The facilities are typically located close to the inmates’ homes, ensuring that they can maintain relationships, and the cells resemble dormitories rather than jails. Norwegian prisoners have the right to vote, receive an education, and see family.

This approach may seem radical, but it has been incredibly successful in Norway. The Scandinavian nation has one of the lowest recidivism rates (20% within 2 years), a dramatic decrease since the 1990s (70-80%, like modern-day USA) when it had a more traditional system. Furthermore, ensuring that prisoners can live normal lives after release benefits the economy. Fewer people in prison means more capable adults available for employment, and many prisoners even leave with additional skills, leading to a 40% increase in employment rates after prison for previously unemployed inmates.

Yet, one drawback is the higher expenses of this system. Norway spends an average of 93,000 USD per year per prisoner, which is potentially unviable for countries with larger prison populations. Such a proposal would also likely be controversial amongst voters, unhappy with their taxpayer dollars being spent on criminals.

And might it be unethical to divert taxpayer funds to lawbreakers? To what extent does one deserve forgiveness? When does an act become unforgivable?

The issue is extremely complex, and realistically, a slightly different setup might be necessary for each unique society. Yet, the approach is undeniably more ethical, and benefits of rehabilitation are well-documented. In Australia, a country with a low population and high recidivism rates, success is highly likely.

Through the recognition that lawbreaking does not definitively indicate moral character and that factors such as socioeconomic status, bias, and even racism can impact the likelihood of incarceration, we can begin to see prisoners as human, too.

Forgiveness is a moral imperative and this is something that our prison system should reflect.

‘I changed my mind about prisons‘ by Sophie Yu is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

BY Sophie Yu

Sophie Yu is a Year 12 student at Redlands, Sydney, where she studies the International Baccalaureate. She is interested in philosophy, culture, and international affairs, and explores these through the mediums of public speaking, writing and the visual arts.

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 11 MAR 2024

It has been some three years since we posed a simple question: to what extent (if any) does ethics affect the economy?

The team we asked to answer that question was led by the economist, John O’Mahony of Deloitte Access Economics. After a year spent analysing the data, the answer was in. The quality of a nation’s ethical infrastructure has a massive impact on the economy. For Australia, a mere 10% improvement in ethics – across the nation – would produce an uplift on GDP of $45 billion per annum. Yes, that’s right, a decade later the accrued benefit would be $450 billion – and growing!

Some things are too good to be true. This is not one of them.

The massive economic impact is a product of a very simple formula: increased ethics=increased trust=lower costs and higher productivity. Increasing trust is the key. Not least because without it, every case for reform will either fall short or fail … no matter how compelling. Ordinary Australians going about their lives simply will not allow reform when they believe that the benefits and especially the burdens of change will be unfairly distributed. So it is that the incredible potential of our nation is held hostage to factors that are entirely within our control.

We invest billions in physical and technical infrastructure in the hope that it will lead to improvement in our lives. We invest almost nothing in the one form of infrastructure that determines how well these other investments will perform. That is, we invest precious little in our ethical infrastructure.

My first reaction to receiving the Deloitte Access Economics report was to try to engage with the Federal Government of the day. I thought that whatever one might think about ‘ethics’ as a concept, there could be no ignoring the economics. I was wrong. The message came back that the government was “positively not interested” in discussing the findings or their implications. I have met with rejection and (more often) indifference on many occasions over the past thirty years. This ranks at the top of my list of negative responses.

The Ethics Centre has always been resolutely apolitical. So, we cast around to find someone in the then Federal Opposition who might engage with the findings. And that is where the current Treasurer, Dr Jim Chalmers, comes in. He took the findings very seriously – so much so that he issued a further challenge to identify what specific measures would increase ethics by 10% and thus, produce the estimated economic uplift. That led to a second piece of work by Deloitte Access Economics – and nine months later, we received the second report. It is that report that has brought forth the current proposal to establish the world-first Australian Institute for Applied Ethics.

The proposed Institute will have two core functions: first, it will be a source of independent advice. Legal issues are referred to the Australian Law Reform Commission. Economic issues are sent to the Productivity Commission. As things stand, there is nowhere to refer the major ethical issues of our times. Second, the Institute will work with existing initiatives and institutions to improve the quality of decision making in all sectors of life and work in Australia. It is important to note here that the Institute will neither replace or displace what is already working well. The task will be to ‘amplify’ existing efforts. And where there is a gap, the Institute will stimulate the development of missing or broken ethical infrastructure.

Above all, such an Institute needs to be independent. That is why we are seeking to replicate the funding model that led to the establishment of the Grattan Institute – by establishing a capital base with a mixture of funds from the private sector and a one-off grant of $33.3 million from the Federal Government.

The economic case for making such an investment is undeniable. The research shows that better ethics will support higher wages and improved performance for companies. Better ethics also helps to alleviate cost of living pressures by challenging predatory pricing practices – and other conduct that is not controlled in a market dominated by oligopolies and consumers who find it hard to ‘shop around’.

But what most excites The Ethics Centre, and our founding partners at the University of NSW and the University of Sydney, is the chance for Australia to realise its potential to become one of the most just and prosperous democracies that the world has ever known. With our natural resources, vast reserves of clean energy and remarkable, diverse population – we have everything to gain … and nothing to lose by aspiring to be just a little bit better tomorrow than we have been today.

And that is why something truly remarkable has happened. ACOSS, the ACTU, BCA and AICD have all come together in a rare moment of accord. Support is growing across the Federal Parliament. Australians from all walks of life – are adding their names in support of an idea whose time has come.

All we need now is our national government to make an investment in a better Australia.

Pledge your support for an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics. Sign your name at: https://ethicsinstitute.au/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Does Australian politics need more than just female quotas?

WATCH

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership