Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureClimate + Environment

BY William Salkeld 7 JUL 2025

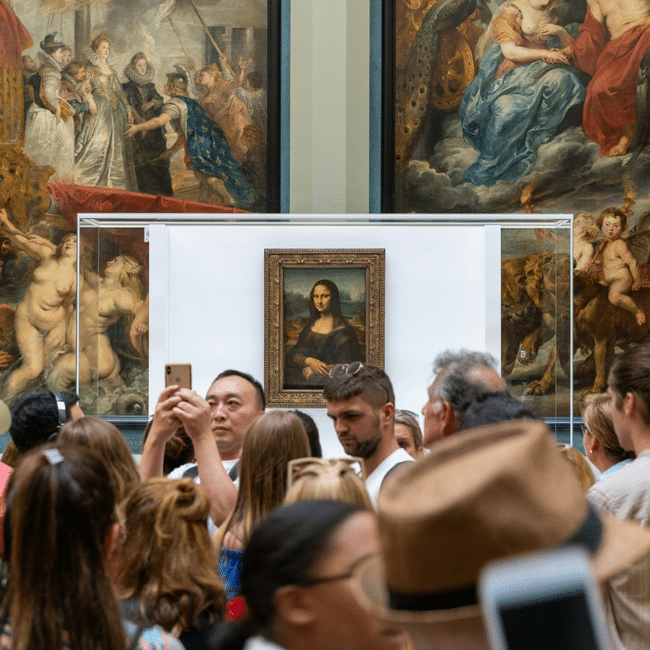

Anyone who’s been privileged enough to have a ‘Euro Summer’ recently would tell you that the hottest tourist spots are overcrowded. Really overcrowded. Think of the lines at popular attractions like Sagrada Familia and Eiffel Tower, or the hordes of travellers in historic cities like Venice and Dubrovnik.

Last summer, protests against overtourism in Barcelona, Spain, made international headlines when a small group of locals began spraying tourists sitting outside a café with water guns. While an isolated water gun incident may seem harmless, there is a deeper moral accusation being made here. Tourists are being blamed for overtourism.

Overtourism happens when the number of tourists in a location is greater than the amount that can comfortably be accommodated. For example, Barcelona has a population of 1.7 million people, but had 15.5 million travellers stay at least one night in 2024.

But can the causes of overtourism be boiled down solely to individual tourists?

It is difficult to impossible for individuals to solve overtourism because it would require significant coordination between hundreds of millions of individual tourists, and for them deprioritise self-interest, while still competing with the interests of businesses, residents, governments and other tourists – otherwise known as a collective action problem.

There are, however, ways that each of these groups can still make a difference.

Individual tourists

Imagine this: after spending months behind a desk daydreaming of the Trevi Fountain in Rome, you find yourself there – alongside thousands of other tourists. You would prefer there were fewer tourists, but you cannot control the actions of others. What individual tourists can control, however, is their behaviour and how they choose to spend their money.

One of the first things that reluctant Year-9 school campers learn in outdoor-ed is to leave no trace in the environment. When tourists leave behind even small amounts of rubbish in the places they travel, it adds up and contributes to environmental degradation. Mt Everest is littered with rubbish left behind by hikers who have ignored local regulations that require them to take 8kg of rubbish with them when they leave. Leaving no trace is a bare minimum for tourists.

Individual tourists can also make conscious decisions to spend their money wisely in a way that gives back to a country’s economy or its residents. Perhaps they can choose to stay at a hotel, rather than book an AirBnB or rental apartment that would have otherwise been available for locals to live in. Or they can spend their money at locally owned businesses rather than chain-restaurants like McDonalds. Given the influence of the user review economy, individuals can choose to leave reviews for businesses with strong ethical credentials, offering valuable support to a struggling tourism economy.

The tourism industry

The tourism industry is an essential part of many economies. In 2022, approximately 11% of Croatia’s GDP – a country home to Dubrovnik (famously, the real-life location of King’s Landing in Game of Thrones) came from tourism. All around the world, the tourism industry can be a vital source of income for locals.

However, the way income from tourism is distributed within a country matters. Bali, a perennial favourite of Aussie travellers, has seen an increased amount of foreign-owned businesses like villas and nightclubs in the past few years. While many employ local residents, foreign-owned businesses can shift income away from the locals. Where possible, tourists should try spending money at locally owned businesses that have a good reputation in the local community for sustainability and ethical practices.

The type of business also contributes to another problem with overtourism: Disneyfication. Strolling through central Amsterdam, you would think the locals spent their time buying souvenirs, eating at restaurants with menus in eight different languages, or smoking at ‘coffee shops’. In reality, most of these businesses are tailored squarely at tourists, turning the urban makeup of the city into a tourist theme-park or commodifying its culture through trinkets. As Barcelona-native Xavier Mas de Xaxàs writes, if overtourism continues, “destinations will continue to lose their real identities and with them an authentic tourist experience.”

One way to avoid having a ‘theme park’ experience is to ask locals what they would do if they were travelling there for the first time. This not only offers a sign of respect to locals, but creates richer and more authentic travel experiences.

Companies like Airbnb were originally designed to help facilitate this interaction, allowing tourists to stay in the homes with locals instead of hotels. They also provide a stream of revenue for local homeowners and significantly contribute to both local economies and the overall tourism sector.

However, in the past decade, short-term rentals like Airbnb have contributed to a growing housing crisis around the world. The problem is that offering short-term rentals for tourists is more lucrative to landlords and property developers than offering long-term leases, meaning apartments that would otherwise have been available for locals to live in are now being rented out to tourists. The greater the overtourism, the greater the effect on housing availability for locals.

Government

No single tourist wants to overcrowd an area but can’t coordinate with other tourists to prevent it from happening.

This is where governments come in. The heart of the problem of overtourism is that too many people end up in one location. Only governments can control how many tourist visas are given out and what percentage of housing can be used for tourist accommodation, and they have a responsibility to do so.

One possible solution is the introduction of a permit system similar to one used in Buddhist Kingdom of Bhutan. The country protects its environmental and cultural heritage from overtourism by charging a tourist tariff of $100 USD per adult per day. One downside, however, is the tariffs price out some potential travellers creating in an inequality in access to travel. Yet too low a price fails to lower entry numbers, demonstrated by the €10 day-entry fees introduced in Venice last year.

Perhaps the best permit system is one where prices are low and the number of permits are limited. In Barcelona’s famous Park Güell, overcrowding is prevented by limiting access to 1400 visitors per day through a low-cost permit system. Whether such a permit system can work at a country or city level remains to be seen, but provides a good model of how governments could regulate overtourism.

Overtourism is a complex problem that will not be solved overnight. It requires a cohesive and collective action from tourists, the industry, and government in a way that is fair to locals and respectful of local customs and laws. While I can’t guarantee that your Euro Summer will be free of surprise water gun attacks, you can sleep easier knowing that you’re being a responsible tourist.

BY William Salkeld

William Salkeld is a PhD candidate with the school of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University, researching interspecies democratic theory. He is interested in animal and environmental ethics, political philosophy, animal minds and cognition, and moral philosophy.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anna Goodman 1 JUL 2025

Young people can often feel torn between the desire to find or start a good job that is financially rewarding while striving to make a positive impact in the world. How should we aim to prioritise the balance between investing in ourselves, our skill sets, and what we feel the world needs?

In 2023, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in philosophy. For most of the first part of my life, my identity centered around learning and being a student. I spent my days in class, reading and writing, and discussing with my close friends about how we wanted to make the world a better place.

Figuring out what I wanted to do after university was a challenge. I knew what I cared about: making sure I continued learning, having opportunities to experience different industries while working with lots of different people, and earning enough money to be able to live well (and maybe save a little). Outside of work, I knew I wanted to be in a place where I would continue to grow to become a true, happy version of myself.

Now two years out of university, I have spent one of those years working as an analyst at a consulting firm. While it is hard work, I’m reaching my career goals of working in different industries, receiving a high investment in training, and earning enough to be a renter in Sydney.

During Christmas break in 2024, about nine months into full time work, I hit a natural point of reflection. Slowing down gave me time to think about what I really wanted from work, and life. I had been working some pretty long hours (as is common in many graduate jobs), and I started to think about what felt worth it to me.

Moral guilt started to creep in, as I began to wonder if I should be spending my time trying to do something more aligned with what I learnt at university and having a career with more purpose. However, with a challenging job market and the continuously rising cost of living, my “logical” brain wonders if it is the right time to make a career move.

So, how can we think about these big career and life decisions in a clear, methodical way?

Ikigai and finding our purpose

It’s hard to distill anything as vast and complex as “work in general” or “life in general” using a simple, one-dimensional framework. That being said, it’s not a new question to ask and reflect on what constitutes meaning in our work and in our lives.

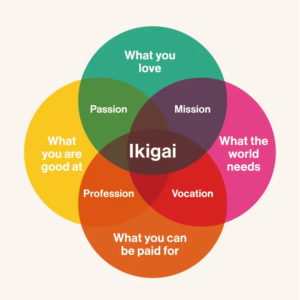

One way we can start to unpack this tension is using the Japanese concept of ikigai – translated roughly to “driving force”. Writers Francesc Miralles and Hector Garcia published their book Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life in 2016, after spending a year travelling around Japan. They interviewed more than 100 elderly residents in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, a community known for its longevity, and one thing that these seniors had in common is that they had something worth living for, or an ikigai.

Ikigai can be summarised into four components:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can get paid for

Asking these questions can get us closer to understanding what intrinsically motivates us and what gives us our reasons for waking up in the morning. Garcia recounts from his interviews with elderly residents in Okinawa: “When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day.”

Reading this, I can’t help but wonder if these answers are a simplification for argument’s sake. Striking a balance between earning enough money to do what I love in my free time (while also paying my bills) and doing something good for the world feels really challenging.

So, how can we make this framework feel more attainable for young people today?

Narrowing the scope

Something I was regularly told as I was applying to graduate jobs was that no one’s first job is perfect. In general, this can be a helpful premise, especially given our interests, circumstances, and contexts can change significantly over time.

One of the ways I began to feel less overwhelmed is by narrowing the ikigai questions around what gives my life meaning to what is giving my life meaning right now. It’s hard to see how I can make a positive contribution to the world through my work, unless I build up skills and knowledge over time that will allow me to have that impact.

For example, when I ask questions about what I love and what I am good at, these answers have changed substantially through my years of formal education and now as a worker. Right now, I have a set of skills I’m good at, however, these will evolve throughout my life and so will my enjoyment of them. In the short term, I enjoy the skills in research, analysis, and problem solving that my current job offers, because I know these are getting me closer to my long-term goal of being able to think pragmatically about key global issues and how we might be able to work to solve them. So, maybe it isn’t always helpful to ask the question “what am I good at” without also asking how this has changed, and how this might continue to change.

As young people, we’re changing and growing up in a world that feels unpredictable and unstable. Technology, culture, politics, economics, and the climate are almost unrecognisable from 10 or 15 years ago. It makes sense that trying to answer our four pillars of ikigai are challenging questions to try and answer if we’re thinking about a time span that gets us through most of our adult lives.

We need ethically minded people in all parts of the world, learning skills and becoming versions of themselves they are proud of. While our jobs are important in teaching and helping us figure out where in the world we want to go, we are more than the work that we do, and our careers, lives, and interests will almost certainly continue to evolve.

Part of graduating is realising that there is a whole wide world of options. This can be liberating and exciting, as well as stressful and overwhelming. By focusing on the “right now” – with regards to what we want, what suits our skills, and what the world needs – hopefully we can begin to wade through the complexities of post-grad life and start to carve a path that is fulfilling, fun and good for society.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Twitter made me do it!

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Making sense of our moral politics

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 JUN 2025

Want to understand politics better? Want to make sense of what the ‘other side’ is talking about? Then take a moment to reflect on your view of an ideal parent.

What kind of parent are you – either in reality or hypothetically? Do you want your children to build self-reliance, discipline, a strong work ethic and steel themselves to succeed in a dog-eat-dog world? Do you want them to respect their elders, which means acknowledging your authority, and expect them to be loyal to your family and community? Do you want them to learn to follow the rules, through punishment if necessary, knowing that too much coddling can leave them lazy or fragile?

Or do you want to nurture your children, so they feel cared for, cultivating a sense of empathy and mutual respect towards you and all other people? Do you want them to find fulfilment in their lives by exploring their world in a safe way, and discovering their place in it of their own accord, supported, but not directed, by you? Do you believe that strictness and inflexible rules can do more harm than good, so prefer to reward positive behaviour rather than threaten them with punishment?

Of course, few people will fall entirely into one category, but many people will feel a greater affinity with one of these visions over the other. This, according to American cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, is the basis of many of our political disagreements. This, he argues, is because many of us intuitively adopt a morally-laced metaphor of the government-as-family, with the state being the parents and the citizens the children, and we bring our preconceived notions of what a good family looks like and apply them to the government.

Lakoff argues that people who lean towards the first description of parenthood described above adopt a “Strict Father” metaphor of the family, and they tend to lean conservative or Right wing. Whereas people who lean towards the second metaphor adopt a “Nurturant Parent” metaphor of the family, and tend to lean more progressive or Left wing. And because these metaphors are so embedded in our understanding of the world, and so invisible to us, we don’t even realise that we see the world – and the role of government – in a very different light to many other people.

Strict Father

The Strict Father metaphor speaks to the importance of self-reliance, discipline and hard work, which is one reason why the Right often favours low taxation and low welfare spending. This is because taxation amounts to taking away your hard-earned money and giving it to someone who is lazy. Remember Joe Hockey’s famous “lifters and leaners” phrase?

The Right is also more wary of government regulation and protections – the so-called “nanny state” – because the Strict Father metaphor says we should take responsibility for our actions, and intervention by government bureaucrats robs us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

The Right is also more sceptical of environmental protections or action against climate change, because they subvert the natural order embedded in the Strict Father, which places humans above nature, and sees nature as a resource for us to exploit for our benefit. Climate action also looks to them like the government intervening in the market, preventing hard working mining and energy companies from giving us the resources and electricity we crave, and instead handing it over to environmentalists, who value trees more than people.

Implicit in the Strict Father view is the idea that the world is sometimes a dangerous place, that competition is inevitable, and there will be people who fail to cultivate the appropriate virtues of discipline and obedience to the rules. For this reason, the Right is less forgiving of crime, and often argues that those who commit serious crimes have demonstrated their moral weakness, and need to be held accountable. Thus it tends to favour more harsh punishments or locking them away, and writing them off, so they can’t cause any more harm.

Nurturant Parent

From the Nurturant Parent perspective, many of these Right-wing views are seen as either bizarre or perverse. The Nurturant Parent metaphor speaks to the need to care for others, stressing that everyone deserves a basic level of dignity and respect, irrespective of their circumstances.

It also acknowledges that success is not always about hard work, but often comes down to good fortune; there are many rich people who inherited their wealth and many hard working people who just scrape by, and many more who didn’t get the care and support they needed to flourish in life. For these reasons, the Left typically supports taxing the wealthy and redistributing that wealth via welfare programs, social housing, subsidised education and health care.

The Left also sees the government as having a responsibility to protect people from harm, such as through social programs that reduce crime, or regulations that prevent dodgy business practices or harmful products. Similarly, it believes that much crime is caused by disadvantage, but that people are inherently good if they’re given the right care and support. This is why it often supports things like rehabilitation programs or ‘harm minimisation,’ such as through drug injecting rooms, where drug users can be given the support they need to break their addiction rather than thrown in jail.

Implicit in the Nurturant Parent metaphor is that the world is generally a safe and beautiful place, and that we must respect and protect it. As such, the Left is more favourable towards environmental and climate policies, even if they mean that we might have to incur a cost ourselves, such as through higher prices.

Bridging the gap

Naturally, there’s a lot more to Lakoff’s theory than is described here, but the core point is that underneath our political views, there are deeper metaphors that unconsciously shape how we see the world.

Unless we understand our own moral worldview, including our assumptions about human nature, the family, the natural order or whether the world is an inherently fair place or not, then it’s difficult for us to understand the views of people on the other side of politics.

And, he argues, we should try to bridge that gap and engage with them constructively.

Part of Lakoff’s theory is that we absorb a metaphor of the family from our own experience, including our own upbringing and family life. That shapes how we make sense of things, like crime, the environment or even taxation policy. So we are already primed to be sympathetic towards some policies and sceptical of others. When we hear a politician speak, we intuitively pick up on their moral worldview, and find ourselves either agreeing or wondering how they could possibly say such outrageous things.

As such, we don’t start as entirely morally and political neutral beings, dispassionately and rationally assessing the various policies of different political parties. Rather, we’re primed to be responsive to one side more so than the other. As such, we don’t really choose whether to be Left or Right, we discover that we already are progressive or conservative, and then vote accordingly.

The difficulty comes when we engage in political conversation with people who hold a different metaphorical understanding of the world to our own. In these situations, we often talk across each other, debating the fairness of tax policy or expressing outrage at each others naivety around climate change, rather than digging deeper to reveal where the real point of difference occurs. And that point of difference could buried underneath multiple layers of metaphors or assumptions about the role of the government.

So, the next time you find yourself in a debate about tax policy, social housing, pill testing at music festivals or green energy, pause for a moment and perhaps ask a deeper question. Ask whether they think that success is due more to luck or hard work. Or ask whether the government has a responsibility to protect people from themselves. Or ask them which is more important: humanity or the rest of nature.

By pivoting to these deeper questions, you can start to reveal your respective moral worldviews, and see how they connect to your political views. You might not convince anyone to adopt your entrenched moral metaphors, but you might at least better understand why you each have the views you have – and you might not see political disagreement as a symptom of madness, and instead see it as a symptom of the inevitable variation in our understanding of the world. That won’t end your conversation, but it might start a new one that could prove very fruitful.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Hey liberals, do you like this hegemony of ours? Then you’d better damn well act like it

Arguments around “queerbaiting” show we have to believe in the private self again

Arguments around “queerbaiting” show we have to believe in the private self again

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 JUN 2025

Back in 2020, pop star Harry Styles caused a stir when he made the supposedly taboo move of appearing on the cover of Vogue magazine wearing a dress.

The stir was probably to be expected, sadly. Though such fashion choices used to go largely uncommented upon, sexuality and gender has become a hot topic issue, and any public suggestions of gender fluidity or queer sexuality tends to prompt hysteria from conservative commentators. But it wasn’t just this group who had something to say. Styles’ dress also prompted a wave of discourse amongst progressives around “queerbaiting”.

Like so many contemporary culture clashes, at the heart of these arguments lie questions about the self: how much of someone else’s identity are we entitled to?

Queerbaiting and the demand for the entire self

At its heart, queerbaiting is a term applied to a suspected marketing strategy. The claim is that some artists and public figures court the attention of queer and allied audiences by pretending to be queer – or at the very least, suggesting that they are – in order to increase their fanbase, general public standing, and sales.

But knowing whether a public figure is actually queerbaiting, or if they are indeed queer, requires demanding access to key aspects of their identity, that once upon a time, we might have been more okay with them keeping private. Queerbaiting thus normalises our desperate hunger for, and perpetuation of, gossip – but here, it casts feeding that desire for gossip as some kind of moral act.

The least harmful examples of these investigations into public figures’ identity markers are basically just online gossip. For example, discussions around the sexuality of actors like Hugh Jackman, or filmmakers like Baz Luhrmann, have existed for a long time. The most harmful examples resemble old-fashioned “outing”. For instance, just a few years ago, one of the key players of the TV show Heartstopper felt pressured into publicly revealing their sexuality to avoid accusations of queerbaiting. “I’m bi,” he wrote. “Congrats for forcing an 18-year-old to out himself. I think some of you missed the point of the show.”

The need for a private self

Discussions about queerbaiting have tricked us into believing that we are not just entitled to a celebrity’s personal life because we are snoops, but because we gain something morally through that demand.

While it might be a well-intentioned, certainly – we should be suspicious of the behaviour of the ultra-rich and public figures trying to gain more capital, particularly when it comes to the harnessing of marginalised identities – that suspicion does not undo the need for privacy.

The demand that people must “out” themselves has always been problematic – but now, in an increasingly dangerous international political climate, such as the Trump administration emboldening anti-LGBTQIA+ groups, it has become actively harmful. When we try to convince ourselves that the entitlement to someone’s sexuality or gender is “logical” or reasonable, we start sliding down a pretty slippery slope, at risk of ending up in a place where marginalised groups have no right to privacy, in a world that has the potential to become only more hostile.

More than that, queerbaiting enforces a categorised, inflexible and outdated understanding of gender and sexuality that progressives have done a lot of work to abandon. Demanding that someone label themselves, when they might not be ready to do so, or might not even have the personal language yet to decide what precise label that they would use, makes the spectrum of sexuality seem unnervingly rigid.

After all, experimenting with a fluid sexuality and gender can be, in some cases, a slow process. Forcing someone to label themselves, when they may just be at the beginning of that journey, goes against so much good work that progressives have done to create a freer culture. The worry is not, necessarily, that celebrities themselves are being harmed by queerbaiting – but that the direction of the public discourse will have a trickle down effect, one that will normalise non-ideal practices and behaviours.

It was the philosopher John Stuart Mill who most carefully laid out the importance of the “private sphere.” For Mill, every person should be entitled to thoughts, beliefs, and sometimes even actions, that were outside the remit of the state and others – that belonged only to them. Mill foresaw that trying to police such a private sphere was akin to a kind of intellectual fascism: as soon as we let go of our private selves, we make our whole selves controllable.

Importantly, Mill believed that actions and beliefs in the private sphere stopped being ungovernable when they harmed others – he did not think that we were just free to do whatever we liked, under the guise of our privacy. But he did believe that we were entitled to a self which was ours and ours alone.

We would do well to remind ourselves of Mill’s argument. Celebrities sign up to giving a great deal of themselves to the public eye – but that does not mean that they need to give all of it. Even a public figure is allowed a private self. And when we forget that, and we start demanding more and more, we normalise the harmful attitude that privacy is something that can be given up, rather than an inalienable right that we should all enjoy.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 19 MAY 2025

A few weekends ago, I made a parenting mistake. I didn’t realise in the moment. The penny didn’t drop, until a good friend made a comment afterwards.

My family was hosting a brunch with several other families. After a few hours in the noisy, sticky, fray, one of our kids asked to retreat. Sensing my hesitation, he pointed out that none of the other guests were of his age.

Partly in acknowledgement, and partly because the retreat he had in mind involved attacking the thistles taking over our front lawn, I let him slip away.

Shortly afterwards, sitting with a group of parents, watching syrup-crazed children run riot out the back, I explained his absence. One parent stopped me at the words “no one my age”. He was wondering, aloud, why age was relevant – let alone a reason to retreat.

The friend who stopped me was one who’d moved to Australia as an adult. He saw the culture he was living in, and the one he’d left, with the benefit of fresh, discerning eyes. Before he finished making it, I saw his point.

Why not expect our kids to socialise with others, regardless of age? Why not encourage them to enjoy the company of those younger than them, and the company of those older than them?

The friend in question told us he’d noticed this propensity to segregate by age before, and resolved not to succumb. He said he makes a point of crossing age divides, of greeting and conversing without discriminating, at social gatherings. Children, in particular, often seem puzzled by his attention. Sometimes they don’t return a greeting, or answer a question, they just stare. The stare might be translated to mean, “Why is this old dude talking to me?” or, “Why would I talk to this old dude?”. Sometimes they mutter something before running off, sometimes they just run off.

As the friend spoke, I recalled a social event where the child who’d just retreated had ended up deep in conversation with a grandparent he’d never met. I wished this image had come to mind earlier, prompted by the words “no one my age”. I knew both he and that grandparent had enjoyed their conversation, maybe as much as the cake, maybe more. It was proof age needn’t be a barrier.

Age needn’t be a barrier, but my friend’s description of children giving him quizzical looks when he acknowledges them suggests us adults are making it one. It suggests so few adults – not counting relatives – take the time to talk to them, that when one does it’s an anomaly.

I consider how much attention I pay to children who aren’t my own at social gatherings.

Sometimes, my attention is on fellow grown-ups and I don’t think to make an effort. At other times, I think to – then I overthink. I see a child and a compliment comes to mind but it’s based on their appearance, or a stereotype, so I censor myself. Or a question comes to mind, but the child in question is a teen and I imagine it will either induce a deep inward groan – “Not another adult asking what I’ll do post-school, how should I know?” – or defensiveness, or self-consciousness, or insecurity…

What lame excuses! If I want my kids to enjoy and initiate interactions and relationships with people of all ages, to throw age-related bias out the window, I should too – even if it requires a little bit of extra effort, creativity, or risk. Who cares if I induce an eye-roll or a groan? What matters is that I don’t just take a genuine interest, and show genuine interest, in adult’s lives, but in the lives of children, too.

I’m sure political philosopher David Runciman also attracts plenty of eye-rolls, as he did at last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas, when arguing that children as young as six should be allowed to vote. After acknowledging that many people find the idea laughable, he turns the question around. “Why shouldn’t they vote?” he asks. “They’re people; they’re citizens; they have interests; they have preferences; there are things that they care about.” Children might make irrational, ill-informed decisions, they might follow their tribe unthinkingly, they might dismiss facts that challenge pre-existing beliefs, but, he points out, adults might too.

“You can’t generalise about children any more than you can generalise about adults,” Runciman says, noting that being well-informed isn’t a prerequisite for voting. Being capable is, and six-year-olds, he argues, are.

Runciman speaks from experience – he once spent a term in an English primary school talking to kids as young as six about politics. Treating them “like they were full citizens”, he arranged for them to participate in the kind of focus groups political parties run for adults. The professional facilitator who ran them said one was among the most inspiring focus group sessions she’d ever been part of.

I’m not convinced children as young as six should be allowed to vote; I am convinced that when we assume we can’t learn from, or socialise with, or befriend them – when we widen the generational divide instead of closing it – we do ourselves and our society a disservice.

I was grateful, and I’m grateful still, that the friend who drew my attention to my parenting mistake didn’t let concern about how it might come across stop him from speaking his mind. Frank honesty is a quality some associate with children. Either way, it’s one that I admire.

I admired his persistence too – despite all those puzzled looks from kids, he’s persevered.

That persistence has paid off. It’s taken months, it’s taken years, but now some children run to him, or look for him at social gatherings. Now some consider him a friend.

For more, tune into David Runciman’s FODI talk, Votes for 6 year olds:

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY Tim Dean 19 MAY 2025

Arts organisations need to strengthen their ethical decision making and communication if they’re to avoid getting caught in controversy.

Which value should arts organisations prioritise? Artistic expression? Or the creation of safe and inclusive spaces, free from divisive issues and the possibility of offence? They often have to choose one because it’s impossible to prioritise both.

Yet, rightly or wrongly, arts organisations are facing demands that they promote both values, with some voices calling for them to prioritise safety at the expense of expression. The sheer impossibility of attempting to satisfy both values – or at least not failing in one of them and triggering a costly backlash – must be keeping the leaders of arts organisations across the country up at night.

There has always been an inherent tension between the values of artistic expression and safety (broadly defined), so there will inevitably be situations where maximising one will compromise the other. Push expression to the extreme and art can be dehumanising or promote hatred. Push safety to the fore and art would lose its power to challenge dominant narratives. This is why the arts have always had to balance the two, often leaning in favour of artistic expression, but with red lines that make things like bigotry or hate speech off-limits.

The challenge today is that we live in an increasingly fractious, polarised and volatile environment, where issues such as the conflict in Gaza are dividing communities and eroding trust and good faith. Where, in times past, onlookers might have treated an ambiguous artwork with charity, now they see endorsement of terror. Where an artist might once have been forgiven for making an off-hand remark in support of a humanitarian cause they believe in, they are now interpreted as promoting hate. This milieu has contributed to many voices – often powerful voices – calling to lower the bar for what is considered “unsafe” and, as a result, seeking to overly constrain expression.

How are arts organisations to continue to fulfil their mandate in such an environment? Given that the issues facing them are fundamentally ethical in nature, the answer comes in strengthening their ethical foundations. One way of doing that is formally adopting a clearly articulated set of values (what they think is good) and principles (the rules they adhere to) that become the sole standard for judgement when individuals make decisions on behalf of their organisation.

Couple that with robust processes for engaging in ethical decision making, and the organisation benefits from making better decisions – and avoiding hasty ones driven by panic or expedience – and is also better able to justify those decisions in the public sphere. There might still be some who criticise the decision, but even a cynic will be forced to acknowledge the consistency and integrity of the organisation.

Of course, arts organisations are not monolithic entities. Leaders and staff will inevitably vary in what they personally think is good and bad or right and wrong. And while individuals have a clear right to decide whether or not they will work with or support a particular organisation, no person can impose their own personal values and principles on those they work with. So, organisations need to have internal processes that allow this diversity to be acknowledged, while arriving at a single set of values and principles that can guide the organisation’s decisions.

And they need to do this without allowing “shadow values and principles” to subvert them. Many organisations have a lovely list of words pinned to the wall or splashed across the ‘About’ page on their website. But their internal culture promotes a different set of values by rewarding or punishing certain behaviours. As a result, it’s possible for an organisation to say it prioritises artistic expression but its actions show it values the patronage of wealthy supporters more, and it’s willing to compromise the former to satisfy the latter.

A truly ethical organisation will be self-aware enough to recognise shadow values and principles when they emerge, and a truly enlightened leadership will be able to redirect the culture towards promoting their stated values and principles.

All of this requires work. But it can be done. I have seen it first hand. I’ve worked with multiple arts organisations to help them better understand the values and principles that they wish to promote, and workshopped a range of scenarios to put its decision making processes to the test.

What would they do if an artist they’ve programmed posts something inflammatory on social media a week before they’re scheduled to perform? What if it was a controversial work from a decade ago? What are the red lines in terms of expression and what are they willing to defend? What would they do if a high-profile donor threatens to pull funding if they don’t deplatform an artist they object to? How should they treat an artist who uses the platform they’ve been given by the organisation to make a political comment unrelated to their work?

The organisations I’ve worked with have answers to these questions. The answers might not satisfy everyone, and they might involve compromises, but they are consistent with the values and principles that drive the organisation.

There may be no single correct answer to many of the ethical challenges that arts organisations face, but there are better and worse answers. Having a robust ethical framework and decision making processes won’t make arts organisations immune to controversy, but it will help them avoid much of it, and enable them to respond with integrity to whatever comes their way.

If you’re an individual or an organisation facing a difficult workplace decision, The Ethics Centre offers a range of free resources to support this process. We also offer bespoke workshops, consulting and leadership training for organisations of all sizes. Contact consulting@ethics.org.au to find out more.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Epicurus

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 14 MAY 2025

One of the most potent allegories ever to be developed by a philosopher is Plato’s allegory of ‘the cave’.

The story centres around a community of people who are bound, from head to toe, while facing a wall. For the entirety of their lives, nothing is to be seen other than two-dimensional shadows cast by whatever passes between their backs and the source of illumination (the sun or a raging fire). Knowing of no other way to see the world, the chained viewers believe that all of reality is represented by the shadows they perceive. Worse still, they have no concept of ‘shadows’ that might shake their conviction that what they see is ‘real’.

Then, one fateful day, a single individual manages to break their bonds. Free to roam, they encounter a three-dimensional world of colour. Then – only then – do they realise that their life has been defined by error; that the shadows that they once took to represent the whole of reality are nothing more than a simplistic rendering of something far more complex, compelling and beautiful. Inspired by this new understanding, the person returns to liberate others. At first, they are mocked, labelled a lunatic and accused of heresy. Eventually, enough people are freed from their shackles and learn to see.

I used to think it was obvious that everyone would jump at the opportunity to be liberated from ignorance. Most of my working life has been animated by Socrates’ great maxim that, “the unexamined life is not worth living”. After all, is it not the capacity to acknowledge – but also to transcend – our instincts and desires, that makes us human? Is it not obvious that a refusal to examine our lives and to make conscious choices, is actually a refusal to embrace the fullness of our humanity? And is it not the task of philosophy – especially ethics – to equip us so that we might better manage complexity once the chains of unthinking custom and practice are loosened?

As it happens, the ‘shadows’ are far more attractive than I had supposed. In a world of increasing complexity, I have been surprised to see an increasing number of people yearning for their chains in the hope that they might recover the simpler two-dimensional world that they have left behind. I see this in an urge to force what is inherently complex into a deceptively simple form. This is an escape back into a world of shadows – an easier path than that of learning how better to deal with complex reality.

The truth is that most of the important things in life are complex. The ‘messiness’ of the human condition comes from the fact that we have the capacity to make conscious (and conscientious) choices in circumstances of radical uncertainty.

Too often, the choice is not between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Values and principles of equal weight can pull us in opposite directions. It is easy to become ‘stuck’, or to face the prospect that the ‘least bad’ alternative is your only viable choice.

Ethics can help us address this messy reality. Not the impossible, flawed ideal of ‘ethical perfection’ – but rather being equipped to live in the uncomfortable light of reality … in all its complexity. We need people to become ‘champions for the common good’. For without dedicated care and attention, our ethical foundations begin to erode.

Ours is a complex world. But when we embrace the ethical dimension of our lives; when we step into the light, nothing can overwhelm and everything becomes possible.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of everyday life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 29 APR 2025

Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Greta Thunberg, Vincent Lingiari, Malala Yousafzai.

For most, these names, and many more, evoke a sense of inspiration. They represent decades and centuries of steadfast moral conviction in the face of overwhelming national and global pressure.

Rosa Parks, risking the limited freedom she was afforded in 1955 America, refused to acquiesce to the transit segregation of the time and sparked an unprecedented boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr.

Frederick Douglass, risking his uncommon position of freedom and power as a Black man in pre-civil rights America, used his standing and skills to advocate for women’s suffrage.

There have always been people who have acted for what they think is right regardless of the risk to themselves.

This is moral courage. The ability to stand by our values and principles, even when it’s uncomfortable or risky.

Examples of this often seem to come in the form of very public declarations of moral conviction, potentially convincing us that this is the sort of platform we need to be truly morally courageous.

But we would be mistaken.

Speaking up doesn’t always mean speaking out

Having the courage to stand by our moral convictions does sometimes mean speaking out in public ways like protesting the government, but for most people, opportunities to speak up manifest in much smaller and more common ways almost every day.

This could look like speaking up for someone in front of your boss, questioning a bully at school, challenging a teacher you think has been unfair, preventing someone on the street from being harassed or even asking someone to pick up their litter.

In each case, an everyday occurrence forces us to confront discomfort, and potentially danger or loss, to live out our values and ideals. Do we have the courage to choose loyalty over comfort? Honesty over security? Justice over personal gain?

The truth is that sometimes we don’t.

Sometimes we fail to take responsibility for our own inaction. Nothing shows this better than the bystander effect: functionally the direct opposite to moral courage, the bystander effect is a social phenomenon where individuals in group or public settings fail to act because of the presence of others. Being surrounded by people causes many of us to offload responsibility to those around us, thinking: “Someone else will handle it.”

This is where another kind of moral courage comes into play: the ability to reflect on ourselves. While it’s important to learn how and when to speak up, some internal work is often needed to get there.

Self-reflection is often underestimated. But it’s one of the hardest aspects of moral courage: the willingness to confront and interrogate our own thoughts, habits, and actions.

If someone says something that makes you uncomfortable, the first step of moral courage is acknowledging your discomfort. All too often, discomfort causes us to disengage, even when no one else is around to pass responsibility onto. Rather than reckon with a situation or person who is challenging our values or principles, we curl up into our shells and hope the moment passes.

This is because moral courage can be – it takes time and practice to build the habits and confidence to tolerate uncomfortable situations. And it takes even more time and practice to prioritise what we think is right with friends, family and colleagues instead of avoiding confrontation in relationships that are already often complicated.

It can get even more complicated once we consider all of our options because sometimes the right ways to act aren’t obvious. Sometimes, the morally courageous thing to do is actually to be silent, or to walk away, or to wait for a better opportunity to address the issue. These options can feel, in the moment, akin to giving up or letting someone else ‘win’ the interaction. But that is the true test of moral courage – being able to see the moral end goal and push through discomfort or challenge to get there.

The courage to be wrong

The flipside to self-reflection is the ability to recognise, acknowledge and reflect with grace when someone speaks up against us.

It’s hard to be told that we’re wrong. It’s even harder to avoid immediately placing walls in our own defence. Overcoming that is the stuff of moral courage too – not just being able to confront others, but being able to confront ourselves, to question our understanding of something, our actions or our beliefs when we are challenged by others.

Whether these changes are worldview-altering, or simply a swapping of word choice to reflect your respect for others, the important thing is that we learn to sit with discomfort and listen. Listen to criticism but also listen to our own thoughts and figure out why our defences are up.

Because in the end, moral courage isn’t just about bold public stands. It’s about showing up—in big moments and more mundane ones—for what’s right. And that begins with the courage to face ourselves.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

WATCH

Society + Culture

Stan Grant: racism and the Australian dream

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Brother is coming to a school near you

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are the Voice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 27 MAR 2025

Adolescence, the exemplary new Netflix series that has become immediate water cooler conversation fodder, is built around a filmmaking decision that might have, in lesser hands, felt like a gimmick. Each of the four episodes of the show are filmed in one continuous, unbroken take.

Here, the decision is not just an inspiring feat of filmmaking verve. It also has a thematic point. Adolescence concerns the murder of a female high school student – the accused is 13-year-old Jamie Miller (Owen Cooper). The show carefully explores the fallout of that violent crime, in particular, what it churns up in the heart of Jamie’s father, Eddie (Stephen Graham, also the show’s co-creator).

The themes of Adolescence are laid out early, and clearly: misogyny; the anger in the heart of teenage boys; and, in particular, the forces that influence adolescents. These themes coalesce in one of the major questions of the show: who shapes the identity of young people, and, pressingly, young men? Is it their parents? The world around them? Or, most worryingly of all, the bad ethical actors who have made their careers through stoking the fires of hatred?

That unblinking, never-cutting camera allows us to explore this question with striking clarity. The camera never looks away. So painfully and shockingly, neither can we.

Who makes our children?

Unlike many other works of art based around crime and murder, Adolescence is not, particularly, a whodunit. It is more like a whydunit. We do have questions early on as to whether Jamie actually committed the crime of which he has been accused, but this is not the focus of the show. Instead, the mystery is a broader, harder, more probing one: why do young men commit acts of violence against women? More specifically, who formed Jamie’s ethical identity?

Eddie, Jamie’s father, seems to worry that it might be him. He spends the show wracked by guilt, confronted with the knowledge of his son’s suspected crime, and terrified that he did not do enough to stop him from walking down a very dark path. But is he solely to blame? The beauty of Adolescence is that it instead leaves those “responsible” for the dark parts of Jamie’s personality nebulous.

In his groundbreaking work, Sources of the Self, philosopher Charles Taylor provides an answer – albeit a worrying one. He argues that identity is formed by a collective. In his view, human beings are defined and constructed through their relationship with others – we become who we are, by virtue of who we interact with. On this view, parents are of course responsible for the shaping of their children’s ethical makeup – but they’re not solely responsible.

And they’re particularly not responsible when adolescence hits. Every parent to teenagers knows that rebellion against the older guard is inevitable – and parents are often the last people that children will confer with. That, according to Taylor, leaves children susceptible to other formative ethical forces – and in the case of Jamie, those are the bad misogynist actors that he is surrounded by, from his schoolmates, to the ever-pressing threat of online radicalisation.

The spectre of the other

Taylor’s view is particularly troubling when combined with the writings of another philosopher, Giorgio Agamben. In his major work, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Agamben argues that ethical identities are especially formed by the rules of inclusion and exclusion. People become who they are by deciding who they are not, forming an in and an out-group that gives them a sense of security in their own personhood.

In Adolescence, it’s exactly that exclusionary nature that seems to lead Jamie down his dark path. His world, like the world of far too many teenage boys, is defined by strict and dangerous binaries: boys versus girls, winners versus losers. His worldview, when we get to hear it, seems defined by hatred for what is different, and a desperate clinging to that, which he sees as the same as himself. When such strict battle lines are drawn, violence is a natural endpoint.

What then do we do to attempt to get our teenage boys back on the right path? Away from violence, hatred, and exclusion? Adolescence, bravely, doesn’t offer a solution. In fact, that’s exactly what Taylor and Agamben show us – that one simple, pat, generic solution doesn’t have the power to change anything.

After all, if we take the work of those philosophers to be true, then we see the entire social environment as constitutive of identity. That means parents. It means friends. It means the entertainment young men consume. It means what they hear in the playground.

Our gaze must significantly broaden – and we must not consider the likes of Jamie to be an outlier. Instead, we must see him as a product of an entire social system.

When, in the final episode of Adolescence, Eddie asks his wife, “shouldn’t we have done better?”, the initial impulse is to assume he means the two of them. The better read is that he means all of us.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Thought experiment: The original position

Thought experiment: The original position

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 20 MAR 2025

If you were tasked with remaking society from scratch, how would you decide on the rules that should govern it?

This is the starting point of an influential thought experiment posed by the American 20th century political philosopher, John Rawls, that was intended to help us think about what a just society would look like.

Imagine you are at the very first gathering of people looking to create a society together. Rawls called this hypothetical gathering the “original position”. However, you also sit behind what Rawls called a “veil of ignorance”, so you have no idea who you will be in your society. This means you don’t know whether you will be rich, poor, male, female, able, disabled, religious, atheist, or even what your own idea of a good life looks like.

Rawls argued that these people in the original position, sitting behind a veil of ignorance, would be able to come up with a fair set of rules to run society because they would be truly impartial. And even though it’s impossible for anyone to actually “forget” who they are, the thought experiment has proven to be a highly influential tool for thinking about what a truly fair society might entail.

Social contract

Rawls’ thought experiment harkens back to a long philosophical tradition of thinking about how society – and the rules that govern it – emerged, and how they might be ethically justified. Centuries ago, thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Lock speculated that in the deep past, there were no societies as we understand them today. Instead, people lived in an anarchic “state of nature,” where each individual was governed only by their self-interest.

However, as people came together to cooperate for mutual benefit, they also got into destructive conflicts as their interests inevitably clashed. Hobbes painted a bleak picture of the state of nature as a “war of all against all” that persisted until people agreed to enter into a kind of “social contract,” where each person gives up some of their freedoms – such as the freedom to harm others – as long as everyone else in the contract does the same.

Hobbes argued that this would involve everyone outsourcing the rules of society to a monarch with absolute power – an idea that many more modern thinkers found to be unacceptably authoritarian. Locke, on the other hand, saw the social contract as a way to decide if a government had legitimacy. He argued that a government only has legitimacy if the people it governs could hypothetically come together to agree on how it’s run. This helped establish the basis of modern liberal democracy.

Rawls wanted to take the idea of a social contract further. He asked what kinds of rules people might come up with if they sat down in the original position with their peers and decided on them together.

Two principles

Rawls argued that two principles would emerge from the original position. The first principle is that each person in the society would have an equal right to the most expansive system of basic freedoms that are compatible with similar freedoms for everyone else. He believed these included things like political freedom, freedom of speech and assembly, freedom of thought, the right to own property and freedom from arbitrary arrest.

The second principle, which he called the “difference principle”, referred to how power and wealth should be distributed in the society. He argued that everyone should have equal opportunity to hold positions of authority and power, and that wealth should be distributed in a way that benefits the least advantaged members of society.

This means there can be inequality, and some people can be vastly more wealthy than others, but only if that inequality benefits those with the least wealth and power. So a world where everyone has $100 is not as just as a world where some people have $10,000, but the poorest have at least $101.

Since Rawls published his idea of the original position in A Theory of Justice in 1972, it has sparked tremendous discussion and debate among philosophers and political theorists, and helped inform how we think about liberal society. To this day, Rawls’ idea of the original position is a useful tool to think about what kinds of rules ought to govern society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Society + Culture

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI)

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships