When we ask ‘what is it ethical for me to do here?’, ethicists usually start by zooming out.

We look for an overarching framework or set of principles that will produce an answer for our particular problem. For instance, if our ethical dilemma is about eating meat, or telling a white lie, we first think about an overarching claim – “eating meat is bad”, or “telling lies is not permissible”.

Then, we think through what could make that overarching claim true: what exactly is badness? The hope is that we will be able to come up with an independently-justified, holistic view that can spit out a verdict about any particular situation. Thus, our ethical reasoning usually descends from the universal to the particular: badness comes from causing harm, eating meat causes harm, therefore eating meat is bad, therefore I should not eat this meat in front of me.

This methodology has led to the development of many grand unifying ethical systems; frameworks that offer answers to the zoomed-out question “what is it right to do everywhere?”. Some emphasise maximising value; others doing your duty, perfecting your virtue, or acting with love and care. Despite their different answers, all these approaches start from the same question: what is the correct system of ethics?

One striking feature of this mode of ethical enquiry is how little it has agreed on over 4,000 years. Great thinkers have been wondering about ethics for at least as long as they have wondered about mathematics or physics, but unlike mathematicians or natural scientists, ethicists do not count many more principles as ‘solid fact’ now than their counterparts did in Ancient Greece.

Particularists say this shows where ethics has been going wrong. The hunt for the correct system of ethics was doomed before it set out: by the time we ask “what’s the right thing to do everywhere?”, we have already made a mistake.

According to a particularist, the reason we cannot settle which moral system is best is that these grand unifying moral principles simply do not exist.

There is no such thing as a rule or a set of principles that will get the right answer in all situations. What would such an ethical system be – what would it look like; what is its function? So that when choosing between this theory or that theory we could ask ‘how well does it match what we expect of an ethical system?’.

According to the particularist, there is no satisfactory answer. There is therefore no reason to believe that these big, general ethical systems and principles exist. There can only be ethical verdicts that apply to particular situations and sets of contexts: they cannot be unified into a grand system of rules. We should therefore stop expecting our ethical verdicts to have a universal-feeling structure, like “don’t lie, because lying creates more harm than good”.

What should we expect our ethical verdicts to feel like instead? What does particularism say about the moment when we ask ourselves “what should I do?”. The particularist’s answer is mainly methodological.

First, we should start by refining the question so that it becomes more particular to our situation. Instead of asking “should I eat meat?” we ask “should I eat this meat?”. The second thing we should do is look for more information – not by zooming out, but by looking around. That is, we should take in more about our exact situation. What is the history of this moment? Who, specifically, is involved? Is this moment part of a trend, or an isolated incident?

All these factors are relevant, and they are relevant on their own: not because they exemplify some grand principle. “Occasion by occasion, one knows what to do, if one does, not by applying universal principles, but by being a certain kind of person: one who sees situations in a certain distinctive way”, wrote John McDowell.

Particularism, therefore, leaves a great deal up to us. It conceives of being ethical as the task of honing an individual capacity to judge particular situations for their particulars. It does not give us a manual – the only thing it tells us for certain is that we will fail if we try to use one.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

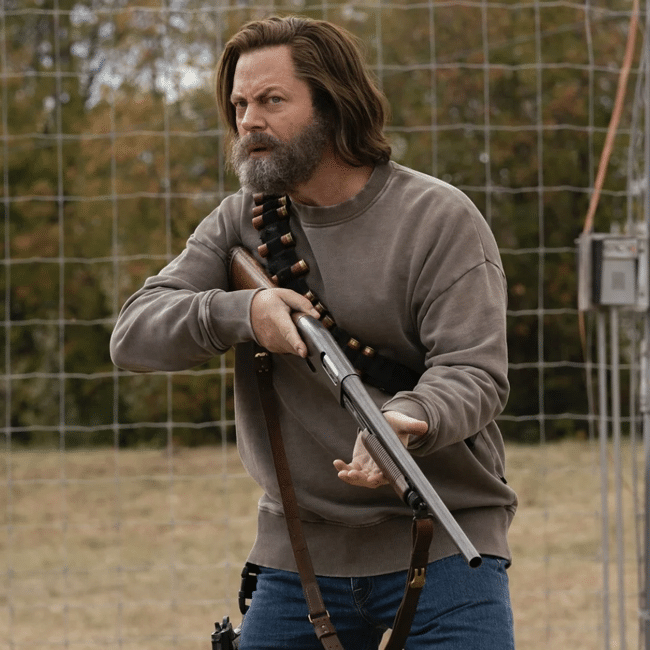

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Corporate whistleblowing: Balancing moral courage with moral responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

James Hird In Conversation Q&A

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships