It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Tim Soutphommasane 25 NOV 2020

Citizenship isn’t often the stuff of inspiration. We tend to talk about it only when we are thinking of passports, as when migrants take out citizenship and gain new entitlements to travel.

When we do talk about the substance of citizenship, it often veers into legal technicalities or tedium. Think of the debates about section 44 of the Constitution or boring classes about the history of Federation at school. Hardly the stuff that gets the blood pumping.

Yet not everything that’s important is going to be exciting. The idea of citizenship is a critical foundation of a democratic society. To be a citizen is not merely to belong to such a society, and to enjoy certain rights and privileges; it goes beyond the right to have a passport and to cast a vote at an election.

To be a citizen includes certain responsibilities to that society – not least to fellow citizens, and to the common life that we live.

Citizenship, in this sense, involves not just a status. It also involves a practice.

And as with all practices, it can be judged according to a notion of excellence. There is a way to be a citizen or, to be precise, to be a good citizen. Of course, what good or virtuous citizenship must mean naturally invites debate or disagreement. But in my view, it must involve a number of things.

There’s first a certain requirement of political intelligence. A good citizen must possess a certain literacy about their political society, and be prepared to participate in politics and government. This needn’t mean that you can only be a good citizen if you’ve run for an elected office.

But a good citizen isn’t apathetic, or content to be a bystander on public issues. They’re able to take part in debate, and to do so guided by knowledge, reason and fairness. A good citizen is prepared to listen to, and weigh up the evidence. They are able to listen to views they disagree with, even seeing the merit in other views.

This brings me to the second quality of good citizenship: courage. Citizenship isn’t a cerebral exercise. A good citizen isn’t a bookworm or someone given to consider matters only in the abstract. Rather, a good citizen is prepared to act.

They are willing to speak out on issues, to express their views, and to be part of disagreements. They are willing to speak truth to power and willing to break with received wisdom.

And finally, good citizenship requires commitment. When a good citizen acts, they do so not primarily in order to advance their own interest; they do what they consider is best for the common good.

They are prepared to make some personal sacrifice and to make compromises, if that is what the common good requires. The good citizen is motivated by something like patriotism – a love of country, a loyalty to the community, a desire to make their society a better place.

How attainable is such an ideal of citizenship? Is this picture of citizenship an unrealistic conception?

You’d hope not. But civic virtue of the sort I’ve described has perhaps become more difficult to realise. The conditions of good citizenship are growing more elusive. The rise of disinformation, particularly through social media, has undermined a public debate regulated by reason and conducted with fidelity to the truth.

Tribalism and polarisation have made it more difficult to have civil disagreements, or the courage to cross political divides. With the rise of nationalist populism and white supremacy, patriotism has taken an illiberal overtone that leaves little room for diversity.

And while good citizenship requires practice, it can all too often collapse into curated performance and disguised narcissism: in our digital age, some of us want to give the impression of virtue, rather than exhibit it more truly.

Moreover, good citizenship and good institutions go hand in hand.

Virtue doesn’t emerge from nowhere. It needs to be seen, and it needs to be modeled.

But where are our well-led institutions right now? In just about every arena of society – politics, government, business, the military – institutional culture has become defined by ethical breaches, misconduct and indifference to standards.

And where can we in fact see examples of the common good guiding behaviour and conduct? In a society where public goods have been increasingly privatised, we have perhaps forgotten the meaning of public things. Our language has become economistic, with a need to justify the economic value of all things, as though the dollar were the ultimate measure of worth.

When we do think about the public, we think of what we can extract from it rather than what we can contribute to it.

We’ve stopped being citizens, and have started becoming taxpayers seeking a return. It’s as though we’re in perpetual search of a dividend, as though our tax were a private investment. As one jurist once put it, tax is better understood as the price we pay for civilisation.

But our present moment is a time for us to reset. The public response to COVID-19 has been remarkable precisely because it is one of the few times where we see people doing things that are for the common good. And good citizens, everywhere, are rightly asking what post-pandemic society should look like.

The answers aren’t yet clear, and we all should consider how we shape those answers. It may just be the right time for us to take citizenship seriously again.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

![]()

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

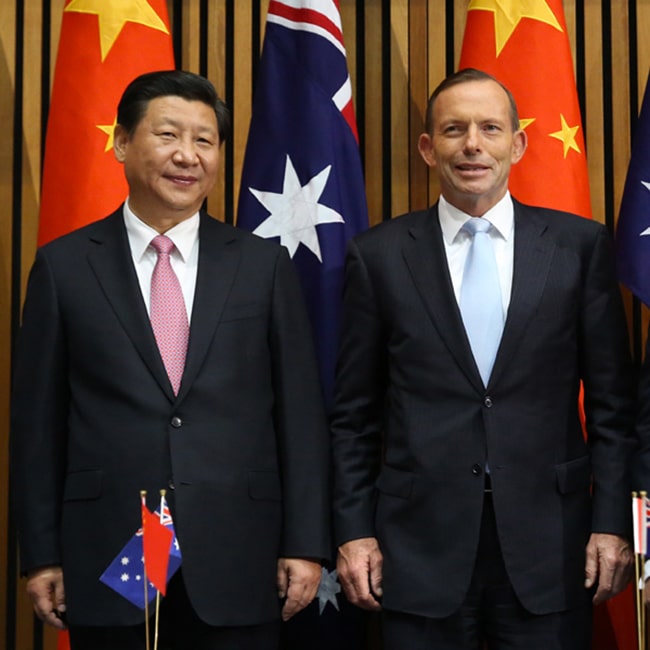

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

BY Tim Soutphommasane

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Bryan Mukandi 25 NOV 2020

The wing of the philosophy department that I occupied during my PhD studies is known as ‘Continental’ philosophy. You see, in Australia, in all but the most progressive institutions, colonial chauvinism so prevails that philosophy is by definition, Western.

A domestic dispute, however, means that most aspiring academic philosophers must choose between the Anglo-American tradition, or the Continental European one. I chose the latter because of what struck me as the suffocating rigidity of the former. Yet while Continental philosophy is slightly more forgiving, it generally demands that one pick a master and devote oneself to the study of the works of this (almost always dead, white, and usually male) person.

I chose for my master a white man of questionable whiteness. Born and raised on African soil, Jacques Derrida was someone who caused discomfort as a thinker in part because of his illegitimate origins. In response, Derrida worked so hard to be accepted that one of the emerging masters of the discipline wrote an approving book about him titled The Purest of Bastards. I, not wanting to undergo this baptism in bleach, ran away into the custody of a Black man, Frantz Fanon.

Born in Martinique, even further in the peripheries of empire than Derrida; a qualified medical practitioner and specialist psychiatrist rather than armchair thinker; and worst of all, someone who cast his lot with anti-colonial fighters – Fanon remains a most impure bastard. My move towards him was therefore a moment of the exercise of what Paul Beatty calls ‘Unmitigated Blackness’ – the refusal to ape and parrot white people despite the knowledge that such refusal, from the point of view of those invested in whiteness, ‘is a seeming unwillingness to succeed’.

It’s not that I didn’t want to succeed. Rather, I found Fanon’s words compelling. The Black, he laments, ought not be faced with the dilemma: ‘whiten yourself or disappear’. I didn’t want to have to put on whiteface each morning. I didn’t want to have to translate myself or my knowledge for the benefit of white comprehension, because that work of translation often disfigures both the work and the translator.

I couldn’t stomach the conflation of white cultural norms with professionalism; the false belief that familiarity with (white) canonical texts amounts to learning, or worse, intelligence; or the assessment of my worth on the basis of my learnt domesticity.

The mistake I made, though, was to assume that moving to the Faculty of Medicine would exempt me from the demand to whiten.

Do you know that sticker, the one you’ll sometimes see on the back of a ute, and often a ute bearing a faux-scrotum at the bottom of the tow bar: “Australia! Love It or Leave It!”? I don’t think that’s a bad summation of the dominant political philosophy in this country. It comes close. Were I to correct the authors of that sticker, I would suggest: “Australia: whiten, or disappear!” This, I think, is the overarching ethos of the country, emanating as much from faux-scrotum laden utes, to philosophy departments, medical institutions, and I suspect board rooms and even the halls of parliament.

What else does, for example, Closing the Gap mean? Doesn’t it boil down to ‘whiten or disappear’, with both reduction to sameness and annihilation constituting paths to statistical equivalence?

I marvel at the ways in which Indigenous organisations manoeuvre the policy, but I suppose First Nations peoples have been manoeuvring genocidal impulses cast in terms of beneficence – ‘bringing Christian enlightenment’, ‘comforting a dying race’, ‘absorption into the only viable community’ – since 1788.

Furthermore, speak privately to Australians from black and brown migrant backgrounds, and ask how many really think the White Australia Policy is a thing of the past. Or just read Helen Ngo’s article on Footscray Primary School’s decision to abolish its Vietnamese bilingual program in favour of an Italian one. As generous as she is, it’s difficult to read the school’s position as anything but the idea that Vietnamese is fine for those with Vietnamese heritage; but at a broader level, for the sake of academic outcomes, linguistic development and cultural enrichment, Italian is the self-evidently superior language.

The difference between the two? One is Asian, while the other is European, where Europe designates a repository into which the desire for superiority is poured, and from which assurance of such is drawn. Alexis Wright says it all far better than I can in The Swan Book.

There sadly prevails in this country the brutal conflation of the acceptance of others into whiteness; with tolerance, openness or even justice.

The Italian-speaking Vietnamese child supposedly attests to ‘our’ inclusivity. Similarly, so long as the visible Muslim woman isn’t (too) veiled, refrains from speaking anything but English in public, and is unflinching throughout the enactment of all things haram (forbidden) – provided that her performance of Islam remains within the bounds of whiteness, she is welcome.

This is why so many the medical students whom I now teach claim to be motivated by the hope of tending to Indigenous, ethnically diverse, differently-abled and poor people. Yet only a small fraction of those same students are genuinely willing to learn how to approach those patients on those patients’ terms, rather than those of a medical establishment steeped in whiteness. To them, the idea of the ‘radical reconfiguration of power’ that Chelsea Bond and David Singh have put forward – that there are life affirming approaches, terms of engagement, even ways of being beyond those conceivable from the horizon of whiteness – is anathema.

Here, we come to the crux of the matter: a radical reconfiguration is called for. Please allow me to be pedantic for a moment. In her Raw Law, Tanganekald and Meintangk Law Professor, Irene Watson, writes about the ‘groundwork’ to be done in order to bring about a more just state of affairs. This is unlike German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Groundwork for a Metaphysics of Morals, by my reading a demonstration of the boundlessness of white presumption and white power, disguised as the exercise of reason. Instead, like African philosopher Omedi Ochieng’s Groundwork for the Practice of a Good Life, but also unlike that text, Watson’s is a call to the labour of excavation, overturning, loosening.

As explained in Asian-Australian philosopher Helen Ngo’s The Habits of Racism, a necessary precondition and outcome of this groundwork – particularly among us settlers, long-standing and more recent, who would upturn others’ lands – is the ongoing labour of ethical, relational reorientation.

Only then, when investment in and satisfaction with whiteness are undermined, can all of us sit together honestly, and begin to work out terms.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

![]()

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

BY Bryan Mukandi

is an academic philosopher with a medical background. He is currently an ARC DECRA Research Fellow working on Seeing the Black Child (DE210101089).

Ethics Explainer: Consent

In many areas of life, being able to say “yes”, to give consent, and mean it, is crucial to having good relationships.

Business relationships depend on it: we need to be able to give each other permission to make contracts or financial decisions and know that the other person means it when they do.

It’s crucial to our relationships with experts who we rely on for critical services, like doctors, or the people who manage our money for us: we need to be able to tell them our priorities and authorise the plans they devise in light of those priorities. And romantic relationships would be nothing if we couldn’t say “yes” to intimacy, sexuality, and the obligations we take on when we form a unit with another person.

Giving permissions with a “yes” is one of our most powerful tools in relationships.

Part of that power is because a “yes” changes the ethical score in a relationship. In all the examples we’ve just seen, the fact that we said “yes” makes it permissible for another person to do something to or with us – when without our “yes”, it would be seriously morally wrong for them to do that very same thing. This difference is the difference of consent.

Defining Consent

Without consent, taking someone’s money is theft: with consent, it’s an investment or a gift. Without consent, entering someone’s home is trespass. With consent, it’s hospitality. Without consent, performing a medical procedure on someone is a ghoulish type of battery. With it, it’s welcome assistance.

The same action looks very morally different depending on whether we have said “yes”. This has led some moral philosophers to remark that consent is a kind of “moral magic”.

Interestingly, there are times when this moral magic can be cast even when a person has not said “yes”. In the political arena, for instance, many philosophers think it doesn’t take very much for you to have consented to be governed. Simply by using roads, or not leaving the territory your government controls, you can be said to have consented to living under that government’s laws.

The bar for what counts as consent is set a lot higher in other areas, like sexual contact or medical intervention. These are cases when even saying “yes” out loud might not be enough to cast the “moral magic” of consent: we can say “yes”, but still not have made it okay for the other person to do what they were thinking of doing.

For instance, if a person says “yes” to sex or to get a tattoo because they are drunk, at gunpoint, ill-informed, mistaken, or simply underage, most ethicists agree it would be wrong for a person to do whatever they have said “yes” too. It would be wrong to give them the tattoo or try to have sex with them, because even though they’ve said “yes”, they haven’t really given consent.

This leads philosophers to a puzzle. If saying “yes” alone isn’t enough for the moral magic of consent, what is?

Do we need the person to have a certain mental state when they say “yes”? If so, is it the mental state, the combination, or just the “yes” that really matters? This is a long and wide-ranging debate in philosophical ethics with no clear answer.

Free and Informed

Recently ethicist Renee Bolinger has argued that the real question is not what consent is, but how best to avoid the “moral risk” of doing wrong. She argues that in this light, we can see that what matters is not what consent is, but what our rules around consent should be, and those rules should consider consent a ‘performance’, or an action, such as speaking or signing something.

Some policy efforts have tried to come up with “rules about consent” that codify when and why a “yes” works its moral magic. There is the standard of “free and informed” consent in medicine, or “fair offers” in contracts law. Ethicists, however, worry that these restrictions are under-described, and simply push the important questions further down the line. For instance, what counts as being informed? What information must a person have, for their “yes” to count as permission?

We might think that knowing about the risks is important. Perhaps a person needs to know the statistical likelihood of bad outcomes. However, physicians know that people tend to over-prioritise relatively small risks, and in emotional moments can be dissuaded from a good treatment plan by hearing of “a three in a million” risk of disaster. So would knowledge of risk be sufficient for informed consent, or do we need to actually know the probability?

There is a final important question for our thinking about consent. Whatever consent is, are there actions you cannot consent to?

A famous court case called R v Brown established in 1993 that some levels of bodily harm are too great for a person to consent to, whether or not they would like to experience that harm. In any area of consent – medicine, financial, sexual, political – this is an important and open question.

Should people be able to use their powers of consent to do harm to themselves? The answer may depend on what we mean by harm.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we need land tax, explained by Monopoly

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 25 NOV 2020

This is the moment when I’m finally going to get my Advanced Level Irony Badge. I’m going to write an opinion piece on why we shouldn’t have so many opinions.

I’ve spent the majority of this week digesting the findings from the IDGAF Afghanistan Inquiry Report. I’m still making sense of the scope and scale of what was done, the depth of the harm inflicted on the Afghan victims and their community at large and how Australian warfighters were able to commit and permit crimes of this nature to occur.

My academic expertise is in military ethics, so I’ve got an unfair advantage when it comes to getting a handle on this issue quickly, but still, I was late to the opinion party. Within an hour or so of the report’s publication, opinions abounded on social media about what had happened, why and who was to blame. This, despite the report being over five hundred pages long.

We spend a lot of time today fearing misinformation. We usually think about the kind that’s deliberate – ‘fake news’ – but the virality of opinions, often underinformed, is also damaging and unhelpful. It makes us confuse speed and certainty with clarity and understanding. And in complex cases, it isn’t helpful.

More than this, the proliferation of opinions creates pressure for us to do the same. When everyone else has a strong view on what’s happened, what does it say about us that we don’t?

We live in a time when it’s not enough to know what is happening in the world, we need to have a view on whether that thing is good or bad – and if we can’t have both, we’ll choose opinion over knowledge most times.

It’s bad for us. It makes us miserable and morally immature. It creates a culture in which we’re not encouraged to hold opinions for their value as ways of explaining the world. Instead, their job is to be exchanged – a way of identifying us as a particular kind of person: a thinker.

If you’re someone who spends a lot of time reading media, you’ve probably done this – and seen other people do this. In conversations about an issue of the day, people exchange views on the subject – but most of them aren’t their views. They are the views of someone else.

Some columnist, a Twitter account they follow, what they heard on Waleed Aly’s latest monologue on The Project. And they then trade these views like grown-up Pokémon cards, fighting battles they have no stake in, whose outcome doesn’t matter to them.

This is one of many things the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had in mind when he wrote about the problems with the mass media almost two centuries ago. Kierkegaard, borrowing the phrase “renters of opinion” from fellow philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote that journalism:

“makes people doubly ridiculous. First, by making them believe it is necessary to have an opinion – and this is perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of the matter: one of those unhappy, inoffensive citizens who could have such an easy life, and then the journalist makes him believe it is necessary to have an opinion. And then to rent them an opinion which, despite its inconsistent quality, is nevertheless put on and carried around as an article of necessity.”

What Kierkegaard spotted then is just as true today – the mass media wants us to have opinions. It wants us to be emotional, outraged, moved by what happens. Moreover, the uneasy relationship between social media platforms and media companies makes this worse.

Social media platforms also want us to have strong opinions. They want us to keep sharing content, returning to their site, following moment-by-moment for updates.

Part of the problem, of course, is that so many of these opinions are just bad. For every straight-to-camera monologue, must-read op-ed or ground-breaking 7:30 report, there is a myriad of stuff that doesn’t add anything to our understanding. Not only that, it gets in the way. It exhausts us, overwhelms us and obstructs real understanding, which takes time, information and (usually) expert analysis.

Again, Kierkegaard sees this problem unrolling in his own time. “Everyone today can write a fairly decent article about all and everything; but no one can or will bear the strenuous work of following through a single solitary thought into the most tenuous logical ramifications.”

We just don’t have the patience today to sit with an issue for long enough to resolve it. Before we’ve gotten a proper answer to one issue, the media, the public and everyone else chasing eyes, ears, hearts and minds has moved on to whatever’s next on the List of Things to Care About.

So, if you’re reading the news today and wondering what you should make of it, I release you. You don’t have to have the answers. You can be an excellent citizen and person without needing something interesting to say about everything.

If you find yourself in a conversation with your colleagues, mates or even your kids, you don’t need to have the answers. Sometimes, a good question will do more to help you both work out what you do and don’t know.

This is not an argument to stop caring about the world around us. Instead, it’s an argument to suggest that we need to rethink the way we’ve connected caring about something with having an opinion about something.

Caring about a person, or a community means entering into a relationship with them that enables them to flourish. When we look at the way our fast-paced media engages with people – reducing a woman, daughter, friend and victim of a crime to her profession, for instance – it’s not obvious this is making us care. It’s selling us a watered-down version of care that frees us of the responsibility to do anything other than feel.

Of course, this is possible. Journalistic interventions, powerful opinion-driven content and social media movements can – and have – made meaningful change in society. They have made people care.

I wonder if those moments are striking precisely because they are infrequent. By making opinions part of our social and economic capital, we’ve increased the frequency with which we’re told to have them, but alongside everything else, it might have diluted their power to do anything significant.

This article was first published on 21 August, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Join our newsletter