Ethics Explainer: Altruism

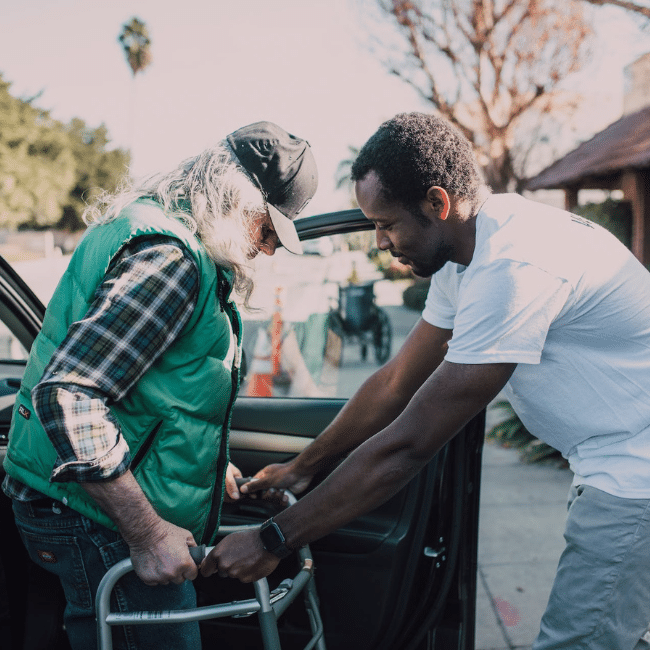

Amelia notices her elderly neighbour struggling with their shopping and lends them a hand. Mo decides to start volunteering for a local animal shelter after seeing a ‘help wanted’ ad. Alexis has been donating blood twice a year since they heard it was in such short supply.

These are all examples, of behaviours that put the well-being of others first – otherwise known as altruism.

Altruism is a principle and practice that concerns the motivation and desire to positively affect another being for their own sake. Amelia’s act is altruistic because she wishes to alleviate some suffering from her neighbour, Mo’s because he wishes to do the same for the animals and shelter workers, and Alexis’ because they wish to do the same to dozens of strangers.

Crucially, motivation is what is key in altruism.

If Alexis only donates blood because they really want the free food, then they’re not acting altruistically. Even though the blood is still being donated, even though lives are still being saved, even though the act itself is still good. If their motivation comes from self-interest alone, then the act lacks the other-directedness or selflessness of altruism. Likewise, if Mo’s motivation actually comes from wanting to look good to his partner, or if Amelia’s motivation comes from wanting to be put in her neighbour’s will, their actions are no longer altruistic.

This is because altruism is characterised as the opposite of selfishness. Rather than prioritising themself, the altruist will be concerned with the well-being of others. However, actions do remain altruistic even if there are mixed motives.

Consider Amelia again. She might truly care for her elderly neighbour. Maybe it’s even a relative or a good family friend. Nevertheless, part of her motivation for helping might also be the potential to gain an inheritance. While this self-interest seems at odds with altruism, so long as her altruistic motive (genuine care and compassion) also remains then the act can still be considered altruistic, though it is sometimes referred to as “weak” altruism.

Altruism can (and should) also be understood separately from self-sacrifice. Altruism needn’t be self-sacrificial, though it is often thought of in that way. Altruistic behaviours can often involve little or no effort and still benefit others, like someone giving away their concert ticket because they can no longer attend.

How much is enough?

There is a general idea that everyone should be altruistic in some ways at some times; though it’s unclear to what extent this is a moral responsibility.

Aristotle, in his discussions of eudaimonia, speaks of loving others for their own sake. So, it could be argued that in pursuit of eudaimonia, we have a responsibility to be altruistic at least to the extent that we embody the virtues of care and compassion.

Another more common idea is the Golden Rule: treat others as you would like to be treated. Although this maxim, or variations of it, is often related to Christianity, it actually dates at least as far back as Ancient Egypt and has arisen in countless different societies and cultures throughout history. While there is a hint of self-interest in the reciprocity, the Golden Rule ultimately encourages us to be altruistic by appealing to empathy.

We can find this kind of reasoning in other everyday examples as well. If someone gives up their seat for a pregnant person on a train, it’s likely that they’re being altruistic. Part of their reasoning might be similar to the Golden Rule: if they were pregnant, they’d want someone to give up a seat for them to rest.

Common altruistic acts often occur because, consciously or unconsciously, we empathise with the position of others.

Effective Altruism

So far, we have been describing altruism and some other concepts that steer us toward it. However, here is an ethical theory that has many strong things to say about our altruistic obligations and that is consequentialism (concern for the outcomes of our actions).

Given that, consequentialism can lead us to arguments that altruism is a moral obligation in many circumstances, especially when the actions are of no or little cost to us, since the outcomes are inherently positive.

For example, Australian philosopher Peter Singer has written extensively on our ethical obligations to donate to charity. He argues that most people should help others because most people are in a position where they can do a lot for significantly less fortunate people with relatively little effort. This might look different for different people – it could be donating clothes, giving to charity, volunteering, signing petitions. Whatever it is, the type of help isn’t necessarily demanding (donating clothes) and can be proportional (donating relative to your income).

One philosophical and social movement that heavily emphasises this consequentialist outlook is effective altruism, co-founded by Singer, and philosophers Toby Ord and Will MacAskill.

The effective altruist’s argument is that it’s not good enough just to be altruistic; we must also make efforts to ensure that our good deeds are as impactful as possible through evidence-based research and reasoning.

Stemming from the empirical foundation, this movement takes a seemingly radical stance on impartiality and the extent of our ethical obligations to help others. Much of this reasoning mirrors a principle outlined by Singer in his 1972 article, “Famine, Affluence and Morality”:

“If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems like a reasonable statement to many people, but effective altruists argue that what follows from it is much more than our day-to-day incidental kindness. What is morally required of us is much stronger, given most people’s relative position to the world’s worst-off. For example, Toby Ord uses this kind of reasoning to encourage people to commit to donating at least 10% of their income to charity through his organisation “Giving What We Can”.

Effective altruists generally also encourage prioritising the interests of future generations and other sentient beings, like non-human animals, as well as emphasising the need to prioritise charity in efficient ways, which often means donating to causes that seem distant or removed from the individual’s own life.

While reasons for and extent of altruistic behaviour can vary, ethics tells us that it’s something we should be concerned with. Whether you’re a Platonist who values kindness, or a consequentialist who cares about the greater good, ethics encourages us to think about the role of altruism in our lives and consider when and how we can help others.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 15 DEC 2023

Can we be too nice? On the surface, it seems absurd to say we should put a cap on how nice we should be. But if we overdo it, we can end up shirking our other ethical obligations.

Skim the headlines or scroll through social media and you’d be forgiven for concluding that there’s a serious deficit of niceness in the world today, and if only people were a little more kind, compassionate and giving, then the world would be a much better place.

Imagine a nicer world where other drivers consistently backed off to let you merge lanes, or shrugged off your occasional failure to check a blind spot with a smile and a wave. Imagine a workplace where everybody lifted each other up, and covered for you when you needed a break. Imagine a world with more Dumbledores and fewer Snapes. Imagine a world without Karens.

Most philosophers have sought such a world by urging us to cultivate niceness. Confucious promoted the foundational virtue of ren, often translated as benevolence or humanity. Aristotle argued that the path to flourishing lay in cultivating virtues like magnanimity, generosity and patience. Christian scholars promoted temperance was a cardinal virtue. In more modern times, Peter Singer has said we ought to take the compassion we feel towards close family and friends and expand it to cover all sentient creatures, human and animal. In short: be nice.

But there’s also a catch with niceness. If we take it to excess, we can leave ourselves vulnerable to exploitation, fail in our ethical duties and even undermine the very moral foundations of our community.

This is because a world where everyone is fully trusting and selflessly giving is a ripe hunting ground for those who are willing to abuse that trust and get ahead by stepping on the backs of others.

The paradox of niceness

This phenomenon can be modelled using the popular game theoretic thought experiment, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine a situation where two bank robbers are arrested and held in separate cells, unable to communicate with each other. The police have no other witnesses, so they’re relying on the suspects’ testimony to prove the case against them. If both suspects confess, they’ll both receive a five-year sentence. If they both remain silent, then the police will only be able to charge them with a minor offense carrying a one-year sentence. However, if one of them testifies while their partner remains silent, then the dobber will be set free while their partner will go to jail for 10 years.

On the surface, it seems sensible for them both to remain silent. That would be the “nice” thing to do because it benefits them both. But there’s a twist. If one of the suspects believes that their partner will remain silent, then they have an opportunity to testify against them and get off scott-free, while their partner is thrown in the slammer. They also know that if they remain silent, then their partner will have an opportunity to dob them in. As a result, the most reasonable thing for either of them to do is dob on the other, which means they both end up with a harsher penalty than if they’d both cooperated and stayed silent.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma models a fundamental truth when it comes to social interaction: if we we’re nice, we all benefit, but there will always be a temptation to exploit the charity of others to get ahead, and in doing so, we can end up destroying the possibility of cooperation altogether.

There have been whole virtual tournaments using the Prisoner’s Dilemma to see what kinds of strategies – whether “nice” or “nasty” – will yield the best results for the agents playing the game. And it’s from these tournaments that another twist emerges.

In a single Prisoner’s Dilemma game, the nasty dobber has the upper hand, especially if their partner is nice. However, when the same agents play the game over and over, it turns out that it pays to be nice, because you’re likely to be punished in the next game if you’ve been nasty. When you add in some real-world flavour to the game, like making it so that agents can sometimes mistakenly defect when they meant to cooperate, it’s the nicer agents that come out on top.

But these simulations show that niceness has its limits. Those agents that are unconditionally nice tend to get exploited by nasty ones. However, those strategies that are conditionally nice, and that defect only to punish bad behaviour, do best of all.

Toxic niceness

Back in the real world, what this means is that it is possible to be too nice. If we’re unconditionally generous and forgiving, then we leave ourselves open to exploitation by people who will take advantage of our niceness.

It’s likely we all know someone who is a natural giver, someone whose empathy is overflowing and who goes out of their way to help everyone around them. These people are often much loved, but they can also be crushed under the weight of their own compassion, sometimes neglecting their own wellbeing, and it’s not uncommon for others to take advantage of their generosity.

Such unconditional niceness can also prevent us from punishing those who deserve it. You may have also worked for a manager who was overly forgiving, not only of minor transgressions, but also behaviour that was toxic or harmful to others. Punishment is inherently unpleasant, and the overly nice can be reluctant to mete it out, staying their hand while wrongdoers run amok. That not only undermines the moral community, but it makes it harder to hold people to account for their actions, preventing them from growing by learning from their mistakes.

Niceness is good. Be nice. But not so nice that you allow others to be nasty.

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships