Making sense of our moral politics

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 JUN 2025

Want to understand politics better? Want to make sense of what the ‘other side’ is talking about? Then take a moment to reflect on your view of an ideal parent.

What kind of parent are you – either in reality or hypothetically? Do you want your children to build self-reliance, discipline, a strong work ethic and steel themselves to succeed in a dog-eat-dog world? Do you want them to respect their elders, which means acknowledging your authority, and expect them to be loyal to your family and community? Do you want them to learn to follow the rules, through punishment if necessary, knowing that too much coddling can leave them lazy or fragile?

Or do you want to nurture your children, so they feel cared for, cultivating a sense of empathy and mutual respect towards you and all other people? Do you want them to find fulfilment in their lives by exploring their world in a safe way, and discovering their place in it of their own accord, supported, but not directed, by you? Do you believe that strictness and inflexible rules can do more harm than good, so prefer to reward positive behaviour rather than threaten them with punishment?

Of course, few people will fall entirely into one category, but many people will feel a greater affinity with one of these visions over the other. This, according to American cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, is the basis of many of our political disagreements. This, he argues, is because many of us intuitively adopt a morally-laced metaphor of the government-as-family, with the state being the parents and the citizens the children, and we bring our preconceived notions of what a good family looks like and apply them to the government.

Lakoff argues that people who lean towards the first description of parenthood described above adopt a “Strict Father” metaphor of the family, and they tend to lean conservative or Right wing. Whereas people who lean towards the second metaphor adopt a “Nurturant Parent” metaphor of the family, and tend to lean more progressive or Left wing. And because these metaphors are so embedded in our understanding of the world, and so invisible to us, we don’t even realise that we see the world – and the role of government – in a very different light to many other people.

Strict Father

The Strict Father metaphor speaks to the importance of self-reliance, discipline and hard work, which is one reason why the Right often favours low taxation and low welfare spending. This is because taxation amounts to taking away your hard-earned money and giving it to someone who is lazy. Remember Joe Hockey’s famous “lifters and leaners” phrase?

The Right is also more wary of government regulation and protections – the so-called “nanny state” – because the Strict Father metaphor says we should take responsibility for our actions, and intervention by government bureaucrats robs us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

The Right is also more sceptical of environmental protections or action against climate change, because they subvert the natural order embedded in the Strict Father, which places humans above nature, and sees nature as a resource for us to exploit for our benefit. Climate action also looks to them like the government intervening in the market, preventing hard working mining and energy companies from giving us the resources and electricity we crave, and instead handing it over to environmentalists, who value trees more than people.

Implicit in the Strict Father view is the idea that the world is sometimes a dangerous place, that competition is inevitable, and there will be people who fail to cultivate the appropriate virtues of discipline and obedience to the rules. For this reason, the Right is less forgiving of crime, and often argues that those who commit serious crimes have demonstrated their moral weakness, and need to be held accountable. Thus it tends to favour more harsh punishments or locking them away, and writing them off, so they can’t cause any more harm.

Nurturant Parent

From the Nurturant Parent perspective, many of these Right-wing views are seen as either bizarre or perverse. The Nurturant Parent metaphor speaks to the need to care for others, stressing that everyone deserves a basic level of dignity and respect, irrespective of their circumstances.

It also acknowledges that success is not always about hard work, but often comes down to good fortune; there are many rich people who inherited their wealth and many hard working people who just scrape by, and many more who didn’t get the care and support they needed to flourish in life. For these reasons, the Left typically supports taxing the wealthy and redistributing that wealth via welfare programs, social housing, subsidised education and health care.

The Left also sees the government as having a responsibility to protect people from harm, such as through social programs that reduce crime, or regulations that prevent dodgy business practices or harmful products. Similarly, it believes that much crime is caused by disadvantage, but that people are inherently good if they’re given the right care and support. This is why it often supports things like rehabilitation programs or ‘harm minimisation,’ such as through drug injecting rooms, where drug users can be given the support they need to break their addiction rather than thrown in jail.

Implicit in the Nurturant Parent metaphor is that the world is generally a safe and beautiful place, and that we must respect and protect it. As such, the Left is more favourable towards environmental and climate policies, even if they mean that we might have to incur a cost ourselves, such as through higher prices.

Bridging the gap

Naturally, there’s a lot more to Lakoff’s theory than is described here, but the core point is that underneath our political views, there are deeper metaphors that unconsciously shape how we see the world.

Unless we understand our own moral worldview, including our assumptions about human nature, the family, the natural order or whether the world is an inherently fair place or not, then it’s difficult for us to understand the views of people on the other side of politics.

And, he argues, we should try to bridge that gap and engage with them constructively.

Part of Lakoff’s theory is that we absorb a metaphor of the family from our own experience, including our own upbringing and family life. That shapes how we make sense of things, like crime, the environment or even taxation policy. So we are already primed to be sympathetic towards some policies and sceptical of others. When we hear a politician speak, we intuitively pick up on their moral worldview, and find ourselves either agreeing or wondering how they could possibly say such outrageous things.

As such, we don’t start as entirely morally and political neutral beings, dispassionately and rationally assessing the various policies of different political parties. Rather, we’re primed to be responsive to one side more so than the other. As such, we don’t really choose whether to be Left or Right, we discover that we already are progressive or conservative, and then vote accordingly.

The difficulty comes when we engage in political conversation with people who hold a different metaphorical understanding of the world to our own. In these situations, we often talk across each other, debating the fairness of tax policy or expressing outrage at each others naivety around climate change, rather than digging deeper to reveal where the real point of difference occurs. And that point of difference could buried underneath multiple layers of metaphors or assumptions about the role of the government.

So, the next time you find yourself in a debate about tax policy, social housing, pill testing at music festivals or green energy, pause for a moment and perhaps ask a deeper question. Ask whether they think that success is due more to luck or hard work. Or ask whether the government has a responsibility to protect people from themselves. Or ask them which is more important: humanity or the rest of nature.

By pivoting to these deeper questions, you can start to reveal your respective moral worldviews, and see how they connect to your political views. You might not convince anyone to adopt your entrenched moral metaphors, but you might at least better understand why you each have the views you have – and you might not see political disagreement as a symptom of madness, and instead see it as a symptom of the inevitable variation in our understanding of the world. That won’t end your conversation, but it might start a new one that could prove very fruitful.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 17 JUN 2025

The first two weeks of June 2025 have seen dramatic demonstrations in the United States against the Trump administration.

Against the backdrop of the President’s campaign of mass deportation, federal agents staged raids at a Home Depot and garment factories in Los Angeles. This triggered spontaneous and sometimes violent protests. Amidst television coverage giving the impression of widespread lawlessness, President Trump deployed some 4,000 members of the California National Guard and 700 U.S. marines – this was done despite the objections of Governor Gavin Newsom, LA Mayor Karen Bass, and the LA Police Department.

This is not unprecedented, but this was the first time troops were deployed on the streets of an American city since the 1992 LA Riots. It was also the first time since 1965 that the Guard was deployed over the objections of a state governor since Lydon Baines Johnson used them to protect citizens marching for civil rights in Alabama.

However, the context matters. These protests in LA in no way matched the scale of the LA Riots of forty years ago, which effectively shut down the city. In 2025 people were still travelling to work; Angelinos were posting photos of family fun from Disneyland. Secondly, Baines Johnson felt the necessity of nationalising the Guard in Alabama because of a widespread organised racist campaign of intimidation against civil rights activists. The was no comparable deprivation of rights in LA (possibly excepting the climate of fear created by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in the city’s Latino population).

The president has these powers, but they are expected to use them within the norms of ‘democratic restraint’ – they should only be used when there is great urgency. This was plainly not the case, considering the LA protests were effectively contained by the LAPD. Governor Newsom delivered a televised address in which he accused Trump of undermining the norms and institutions of democratic government in the United States and that California was being used to test a broader authoritarian power grab.

America is showing many of the signs of ‘democratic backsliding’. In How Democracies Die, political scientists at Harvard, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, have identified symptoms of a dying democracy. Many people think of military coups and tanks on the streets, but democracies often have slower, less spectacular deaths. Levitsky and Ziblatt show that elected leaders manage to neutralise and co-opt other branches of government; we have seen this with the collapse of moderate voices in the Republican Party and many express deep reservations about the Supreme Court’s independence after the genuinely shocking ruling for Trump v. United States which effectively placed the president above the law.

It is not just the institutional stress, but the growing incivility of civil society that is a concern, because institutions and constitutions do not defend themselves. They require people to unite to support common ways of life.

Americans are now deeply polarised. Political opponents are no longer competitors but enemies, or even traitors, to be silenced. It is impossible to disassociate this from the global pandemic of social media brain rot spreading disinformation, hatred, and conspiracy theories. The erosion of checks and balances coupled with the polarisation of civil society has enabled democratic norms to be slowly eroded to the extent that the President feels able to govern without traditional restraint.

So then what are the duties of citizens in a democracy that, if not dying, is looking terribly ill? This is not a partisan issue, but one that addresses the basic structure of society.

John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice, perhaps the greatest work of American political philosophy, that we all have a ‘natural duty’ to build and uphold just social institutions. This is because these institutions are the condition by which we can exercise our minimal autonomy. There is an assumption here that there is something intrinsically valuable about being able to think up and pursue one’s idea of a good life (so long as it doesn’t step on other people’s ability to do the same). You cannot do this if your choices are contingent on the will of a powerful person, whether it is your boss or the president. This is why the founders of the United States opted for a republic over a monarchy as the best guarantee of freedom from domination. It is a matter that should concern all Americans regardless of their political preferences.

Yet, it is a fragile system. On the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Benjamin Franklin was asked by his friend Elizabeth Willing Powel whether the United States was to be a monarchy or a republic, to which he replied, “a republic if you can keep it”. It is easy to imagine states, especially ones as powerful as the United States, as permanent, but history is a graveyard of states, including many democracies.

What then are citizens to do in circumstances where democracy is failing? We find a suggestion in Franklin’s words. It is up to the people. What makes Franklin’s quote so interesting is that he addressed it to someone who could not even vote: a republic if you can keep it. The suggestion being that all people, even the disenfranchised, share this natural duty to preserve and uphold just institutions. The addressee of Franklin in the 21st century could well be the illegal immigrants who despite being demonised are an integral part of the American economy and society. The protests in LA may have been alarming, but they were a distress call from some of the most vulnerable people in the United States.

The question is how long can this continue? The problem with socialism, Oscar Wilde quipped, is that it takes up too many evenings. The same can be said about resisting authoritarianism. People need to live their lives, you can’t spend every waking hour protesting. Authoritarians know this and take their time eroding the guardrails and poisoning civil society. Trump with characteristic impatience is trying to do in months what took Viktor Orban and Hugo Chavez years to accomplish in much weaker democracies. The experience of the past two weeks may have chastened Trump, but it won’t stop him. The citizens of the United States are in a race against autocracy, but it is not a sprint. It is a marathon.

What every person in the United States, both citizens and non-citizens, must ask themselves is how best can I exercise my natural duty to support just institutions when they are under threat? It is an imperfect duty, meaning that it can be cashed out in numerous ways, but here are 3 suggestions:

- Vote for democracy: In instances of authoritarian capture people must put country above party. When a mainstream party, either of the left or the right, is infected by authoritarianism it is time to find a new political home until the fever breaks.

- Depolarise your politics: Democracies die when people lose what philosopher Michael Oakeshott called a ‘common tongue’ – the shared practices and customs that turns strangers into compatriots. Just as some people must make a new political home, others have a duty to welcome them. Your neighbour is not your enemy, even when you disagree.

- Take it to the streets: Vocal and visible rejection of authoritarianism by a united front reminds people that the decline of democracy is not inevitable; think of the contrast between the aptly named “No Kings” protests and Trump’s farcically shabby birthday parade. Public defiance is essential to maintain the health of civil society.

And it should also be said all of us observing from the sidelines must ask ourselves how we can exercise the same duty to prevent our democracies from going the same way.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

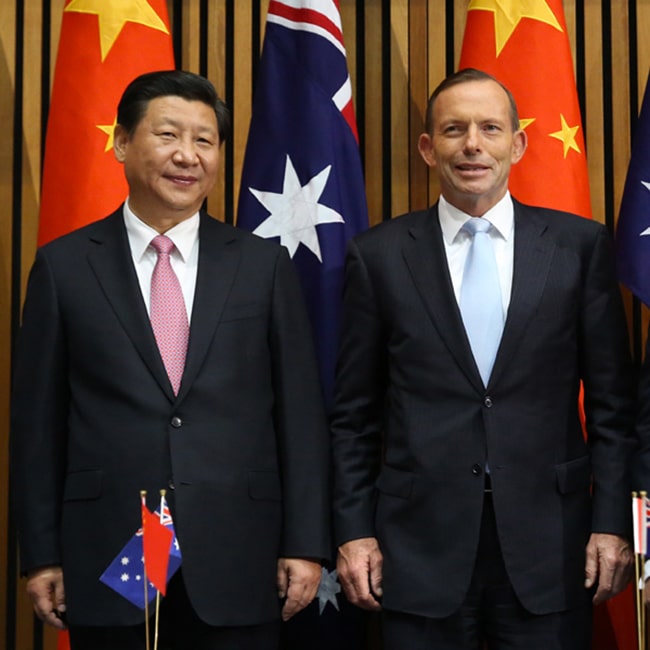

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Reports

Politics + Human Rights