Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anna Goodman 1 JUL 2025

Young people can often feel torn between the desire to find or start a good job that is financially rewarding while striving to make a positive impact in the world. How should we aim to prioritise the balance between investing in ourselves, our skill sets, and what we feel the world needs?

In 2023, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in philosophy. For most of the first part of my life, my identity centered around learning and being a student. I spent my days in class, reading and writing, and discussing with my close friends about how we wanted to make the world a better place.

Figuring out what I wanted to do after university was a challenge. I knew what I cared about: making sure I continued learning, having opportunities to experience different industries while working with lots of different people, and earning enough money to be able to live well (and maybe save a little). Outside of work, I knew I wanted to be in a place where I would continue to grow to become a true, happy version of myself.

Now two years out of university, I have spent one of those years working as an analyst at a consulting firm. While it is hard work, I’m reaching my career goals of working in different industries, receiving a high investment in training, and earning enough to be a renter in Sydney.

During Christmas break in 2024, about nine months into full time work, I hit a natural point of reflection. Slowing down gave me time to think about what I really wanted from work, and life. I had been working some pretty long hours (as is common in many graduate jobs), and I started to think about what felt worth it to me.

Moral guilt started to creep in, as I began to wonder if I should be spending my time trying to do something more aligned with what I learnt at university and having a career with more purpose. However, with a challenging job market and the continuously rising cost of living, my “logical” brain wonders if it is the right time to make a career move.

So, how can we think about these big career and life decisions in a clear, methodical way?

Ikigai and finding our purpose

It’s hard to distill anything as vast and complex as “work in general” or “life in general” using a simple, one-dimensional framework. That being said, it’s not a new question to ask and reflect on what constitutes meaning in our work and in our lives.

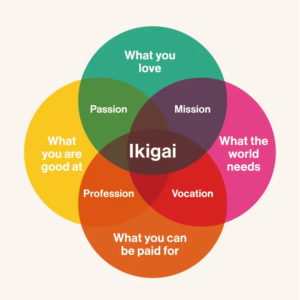

One way we can start to unpack this tension is using the Japanese concept of ikigai – translated roughly to “driving force”. Writers Francesc Miralles and Hector Garcia published their book Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life in 2016, after spending a year travelling around Japan. They interviewed more than 100 elderly residents in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, a community known for its longevity, and one thing that these seniors had in common is that they had something worth living for, or an ikigai.

Ikigai can be summarised into four components:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can get paid for

Asking these questions can get us closer to understanding what intrinsically motivates us and what gives us our reasons for waking up in the morning. Garcia recounts from his interviews with elderly residents in Okinawa: “When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day.”

Reading this, I can’t help but wonder if these answers are a simplification for argument’s sake. Striking a balance between earning enough money to do what I love in my free time (while also paying my bills) and doing something good for the world feels really challenging.

So, how can we make this framework feel more attainable for young people today?

Narrowing the scope

Something I was regularly told as I was applying to graduate jobs was that no one’s first job is perfect. In general, this can be a helpful premise, especially given our interests, circumstances, and contexts can change significantly over time.

One of the ways I began to feel less overwhelmed is by narrowing the ikigai questions around what gives my life meaning to what is giving my life meaning right now. It’s hard to see how I can make a positive contribution to the world through my work, unless I build up skills and knowledge over time that will allow me to have that impact.

For example, when I ask questions about what I love and what I am good at, these answers have changed substantially through my years of formal education and now as a worker. Right now, I have a set of skills I’m good at, however, these will evolve throughout my life and so will my enjoyment of them. In the short term, I enjoy the skills in research, analysis, and problem solving that my current job offers, because I know these are getting me closer to my long-term goal of being able to think pragmatically about key global issues and how we might be able to work to solve them. So, maybe it isn’t always helpful to ask the question “what am I good at” without also asking how this has changed, and how this might continue to change.

As young people, we’re changing and growing up in a world that feels unpredictable and unstable. Technology, culture, politics, economics, and the climate are almost unrecognisable from 10 or 15 years ago. It makes sense that trying to answer our four pillars of ikigai are challenging questions to try and answer if we’re thinking about a time span that gets us through most of our adult lives.

We need ethically minded people in all parts of the world, learning skills and becoming versions of themselves they are proud of. While our jobs are important in teaching and helping us figure out where in the world we want to go, we are more than the work that we do, and our careers, lives, and interests will almost certainly continue to evolve.

Part of graduating is realising that there is a whole wide world of options. This can be liberating and exciting, as well as stressful and overwhelming. By focusing on the “right now” – with regards to what we want, what suits our skills, and what the world needs – hopefully we can begin to wade through the complexities of post-grad life and start to carve a path that is fulfilling, fun and good for society.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

If it’s not illegal, should you stop it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 14 NOV 2024

Some psychologists believe that we become the average of the people we spend the most time with. However, this can make things complicated for our own morals, ethics, and values.

In the middle of 2020, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Malala Yousafzai was harassed on Twitter for endorsing her conservative friend at Oxford University. It made headlines around the world, with thousands of people commenting on who they felt they could and couldn’t be friends with out of principle.

While friendships often transcend differences of opinion, most people have limits on what values and beliefs they will tolerate in the people they spend time with. It’s important to ask ourselves: does being friends with someone mean agreeing with all their values and beliefs? Or can we be friends with someone we disagree with?

There is more to friendship than simply sharing values and beliefs

When we enter into a friendship, we are agreeing to a set of duties and expectations of what it means to be a good friend. These duties can involve providing support during difficult times, celebrating accomplishments, being caring and empathetic, and so on.

However, it’s unlikely we’ll have friends who we agree with 100% of the time. This could mean disagreeing with a choice they made, or realising that you have differing values about something. It is perfectly reasonable to disagree with a friend or hold an opposing view, and not be hypocritical in your own beliefs.

It’s important to interrogate, though, what this means for us. When Malala was harassed online for having a friend with different political views, it wasn’t because she herself expressed those views. Rather, it was because she supported a friend with different views, and that support supposedly had to have indicated something about her own values and beliefs.

Friendships, however, are so much more than shared values. Having people in our lives with different values and opinions can broaden our perspective on the world, while also providing us with the opportunity to question the reasoning behind our own beliefs.

Even though there is more to a person than both their views and the views of their friends, it is naïve to claim that our friends’ values don’t have an impact on us.

So, there has to be a threshold of tolerance in what we are willing to understand in our friends’ values. The ethical dilemma we find ourselves in is where we draw the line.

There is no doubt that some categories of opinions and values shouldn’t be given the same airtime as others. One way we can discern this is by asking: what are the implications on others in expressing or acting on this belief?

Some beliefs predominantly impact the individual who holds them. Food preferences, opinions about what clothes look good, or what music sounds best are unlikely to have a significant effect on the people in this person’s life.

However, expressing or acting on other kinds of beliefs can have obvious, negative impacts on certain groups of people such as racist, sexist or homophobic rhetoric, disinformation, and hate speech. Understanding that expressing some kinds of beliefs has an impact on the broader community characterises the harm of unchecked intolerance.

When we overlook a friend’s more severe hateful or discriminatory belief, we can become complicit in allowing a belief that harms others to go unchecked.

Overlooking a hateful or discriminatory belief the same way that we might overlook a difference in taste or preference makes it seem like we are condoning, if not supporting, that belief. For example, if your friend was continuously espousing hate speech and you didn’t call them out on it, it doesn’t matter if you didn’t partake in hate speech yourself. By letting it slide because it’s a friend, the harm of expressing these values is still being done. Challenging and speaking out about that belief doesn’t mean that we are being a bad friend – in fact, it usually means the opposite.

One possible solution: deal breakers

Even though we can’t expect to have all the same values as our friends, we might expect that we have the same deal breakers as them. A deal breaker is something like a value or personality trait that will cause a person to back out of a relationship or agreement. For example, one of the things that might connect us to our friends is that we all have a deal breaker that we won’t tolerate someone who is rude or unkind to strangers. Having the same deal breakers means that we draw the same line in the sand of what we will and won’t tolerate, rather than ensuring that we agree on every single value.

The concept of a deal breaker can be helpful with ethical value differences in our friends, too. For example, it could be that we’re happy with different approaches to ethical decision making, as long as we both won’t tolerate anything that harms others unnecessarily. Instead of making sure we agree with our friends entirely, we’re making sure we’re on the same page about the “non-negotiable” values we have.

As with most ethical issues, the answer is rarely black and white. In this case, the line we draw with what values we tolerate in our friends can often fluctuate due to external factors, including mental health and personal context.

At the end of the day, being someone’s friend shouldn’t mean that you have to defend every single belief that they have. I would hope that my friends feel that they can challenge my beliefs, and that I can do the same for them. However, it is important that we think about the deal breakers we have and hold our friends accountable for how their beliefs impact the broader population, and be willing to look inward when they do the same for us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Anna Goodman 17 JAN 2023

Reparations recently made the news after the COP27, with poorer countries demanding richer countries pay for damages caused by global warming. But, are reparations the best way to achieve justice for previous harms, and what do they tell us about moral responsibility?

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, western countries developed and industrialised without many (or any) regulations. Coal burning factories produced new technologies, new agricultural practices led to chemical runoff and land clearing, and global trade and travel have accelerated the production of man-made greenhouse gases. Historically, developed countries have contributed to just under 80% of total carbon emissions.

As a result, devastating floods, bush fires, droughts and storms have ruinous impacts on communities and countries. Rising sea levels threaten small island nations and coastal towns alike. The countries and populations feeling the biggest impacts tend to be poorer and have fewer resources to deal with the fallout of climate related catastrophes.

Climate change is a global issue, and it’s clearly impacting poorer, less developed countries in more drastic ways than wealthier ones. Can reparations really be a solution to such a complex issue?

What are reparations?

Reparations are usually monetary (or something else that transfers wealth, like land) compensation, paid by a dominant group to an individual or a group that has been wronged or harmed. Reparations are usually viewed as one mechanism for remedying a past injustice. Given past injustices have created present-day inequalities and much of this inequality is socioeconomic, reparations are one way to make amends and “even the playing field.

The controversy surrounding reparations

Reparations become controversial when we overlay our common conceptions of moral responsibility. We typically view someone as morally responsible for something if they caused that thing to happen. For example, if you steal something from a store and are fully aware and in control of yourself, most people would view you as morally responsible for that action, and therefore deserving of the repercussions that come from stealing.

But, who is morally responsible for the global climate crisis? European countries have some of the most progressive climate change policies in the world today, but were responsible for the majority of emissions during the 19th and 20th centuries. On the other hand, China and India haven’t historically been big emitters, but today they are. It’s unclear who is more responsible for the state of the climate today. So, if we can’t find someone or some group directly morally responsible, should reparations be paid at all?

The case for reparations

There are two main reasons why I think our common notion of moral responsibility translates into a good enough argument in favour of reparations.

Firstly, we need to think about what inequality looks like in the world. Much of the inequality that we can observe is economic, and it is often the direct result of past injustices.

If we truly want to live in a just world, we are going to need to level the playing field, and money is one of the most effective ways to do that.

The question is: where should this money come from? Whether or not someone from a dominant group actively participated in or committed one of these wrongs, they likely experienced either direct or indirect benefits.

For example, industrialised countries have benefited from the use of fossil fuels, and generated their wealth through manufacturing and trade, which compounded over decades and centuries. To the extent that individuals and groups today have benefited from past injustices, then they owe some reparations to the groups that are disadvantaged because of those past injustices. Wealthy countries, therefore, that have compounded wealth that came from industrialising during a time where carbon emissions remained unchecked should pay reparations, even though none of the people alive today actively contributed to the climate emissions of the past.

Second, reparations acknowledge that the payer has some responsibility for the wrongs committed towards the payee. As former prime minister Scott Morrison said about $280 million of reparations that Aboriginal communities received in 2017, “This is a long-called-for step… to say formally not just that we’re deeply sorry for what happened, but that we will take responsibility for it”. Paying reparations acknowledges that harm occurred to a group of people because it recognises that there is lasting inequality that has occurred from that harm. In addition, the person or group paying the reparations recognises that they have benefitted from the harm or inequality, even if they didn’t directly cause it.

While reparations don’t promise to remove all inequality or solve every injustice, they are an important step for dominant groups to acknowledge and accept responsibility for harms of the past, as well as taking an important step to close present socioeconomic gaps.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 12 OCT 2022

As it stands, in the western world, marriage is the legal union between two people who are typically romantic or sexual partners. Some philosophers are now revisiting the institution of marriage and asking what can be done to reform it, and if it should exist at all.

The institution of marriage has been around for over 4,000 years. Historians first see instances of marriages popping up around 2350 BCE in Mesopotamia, or modern day Iraq. Marriage turned a woman into a man’s object whose primary purpose was producing legitimate offspring.

Throughout the following centuries and millennia, the institution of marriage evolved. As the Roman Catholic church grew in power throughout the 6th, 7th, and 8th centuries, marriage became widely accepted as a sacrament, or a ceremony that imparted divine grace on two people. During the Middle Ages, as land ownership became an important part of wealth and status, marriage was about securing male heirs to pass down wealth and increasing family status by having a daughter marrying a land-owning man.

“The property-like status of women was evident in Western societies like Rome and Greece, where wives were taken solely for the purpose of bearing legitimate children and, in most cases, were treated like dependents and confined to activities such as caring for children, cooking, and keeping house.”

The thinking that a marriage should be about love really only began in the 1500s, during a period now known as the Renaissance. Not much improved with regard to equality for women, but the movement did put forth the idea that two parties should enter a marriage consensually. Instead of women being viewed as property to be bought and sold with a dowry, women had more autonomy which elevated their social status. Into the 1700s, while the working class were essentially free to marry who they wanted (as long as they married people in the same social class), girls born into aristocratic families were betrothed as infants and married as teenagers in financial alliances between families.

But marriage doesn’t look like this anymore, right? It’s easy to forget that interracial marriage was illegal in the United States until 1967 and until 1985 in South Africa. Marital rape only became a crime in all American states in 1993. Australia only legalised gay marriage at the end of 2017, making it one of 31 countries to do so. In the 4,000 years of marriage, most legalised marriage equality has happened in the last 50 years.

The nasty history of marriage has prompted some philosophers to ask: is it time to get rid of the institution of marriage? Or, is it possible to reform?

An argument for the abolition of marriage

“Freedom for women cannot be won without the abolition of marriage.”

In the last hundred years, there has been plenty of discourse about where marriage fits into modern life. One notable voice, Sheila Cronan, a feminist activist who participated actively in the second wave feminist movement in America, argued that marriage is comparable to slavery, as women performed free labour in the home and were reliant on their husbands for financial and social protection.

“Attack on such issues as employment discrimination are superfluous; as long as women are working for free in the home we cannot expect our demands for equal pay outside the home to be taken seriously.”

Cronan believed that it would be impossible to achieve true gender equality as long as marriage remained a dominant institution. The comparison of marriage to slavery was hugely controversial, though, because white women had significantly better living conditions and security than slaves. In a modern, western context, Cronan’s article may seem like a bit of an overstatement on the woes of marriage.

Is there an alternative to abolition?

Another contribution to the philosophy of marriage is the work of Elizabeth Brake. Instead of abolishing marriage, she puts forward a theory in her 2010 paper What Political Liberalism Implies for Marriage Law called “minimal marriage,” which claims that any people should be allowed to get married and enjoy all the legal rights that come with it, regardless of the kind of relationship they are in or the number of people in it.

Brake argues that when the state allows some kinds of marriages but not other kinds, the state is asserting one kind of relationship as more morally acceptable than another. Marriage in the western world provides a number of legal benefits: visitation rights in hospitals if someone gets sick, fewer complications around joint bank accounts, and the right to inherit the estate if a partner dies, to name a few. It is also often viewed as a better or superior kind of relationship, so those who are not allowed to get married are seen as being in an inferior kind of relationship.

Take for example the case of two elderly women who are close friends and have lived together for the last 30 years. If one of the elderly women falls ill and needs to go to hospital, her friend might not be able to visit her because she is not a spouse or next-of-kin. If she passes away and her friend is not in her will, then the friend will have no say over what happens to her estate. The reason these friends were not married was because they felt no romantic attraction to each other. But Brake asks us: why should their relationship be seen as less valuable or less important than a romantic one? Why should their caring relationship not be afforded the legal rights of marriage?

Many legal rights are tied to marriage. In the US, there are over 1000 federal “statutory provisions,” or clauses written in the law, in which marital status is a factor in determining who gets a benefit, privilege, or right. Brake argues that reforming marriage to be “minimal” is the best way to ensure that as many people as possible have these legal rights.

So, what should the future of marriage be?

Many people today will say that the day they got married was one of the best days of their lives. However, just because we have a more positive view of it now does not erase the thousands of years of discriminatory history. In addition, practices such as child marriage and arranged marriages that no longer occur in the western world are still the norm in other parts of the world.

While Cronan presents a strong argument for abolishing marriage and Brake presents a strong argument for its reform , we need to examine the underlying social ills that make marriage so complicated. Additionally, there’s no guarantee that abolishing or reforming marriage will eliminate the sexism, racism, and homophobia that create the conditions for marriage to be so discriminatory in the first place. Marriage may not be creating inequality as much as it is a symptom of inequality. While the question of what to do with marriage is worth interrogating, it’s important to consider the larger role it might play in creating social change and working towards equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 13 SEP 2022

There will always be people in the world who have different opinions, values, and beliefs from our own. But this shouldn’t stop us from listening to those we know we disagree with, even if we think it’s unlikely that we will change our minds.

During part of the Covid-19 pandemic, I lived with my grandfather in rural Vermont, a small state in the north-east of the US. Being Australian, I had many opportunities to talk to people I would not have otherwise have had a chance to meet. Then, the 2020 presidential election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump rolled around, and it was all anyone could talk about.

My grandfather’s carer voted for Trump in 2020. I got to know her quite well – she’s a life-long rural north-easterner with a strong belief in individual self-sufficiency. We talked a lot about the differences between where we came from. Politics always comes up in conversation around an election, so naturally it came up that we would support different presidential candidates.

Most of the media that I consume and the majority of my social circle reinforce my liberal political views. Talking with my grandfather’s carer gave me a different perspective on why someone would vote for Trump. While her reasoning didn’t convince me to change my vote, I came to understand how my life led me to my beliefs on who should be president, and her life led to hers.

These conversations inspired me to think a little more about what we gain when we take the time to listen thoughtfully to people with different views, perspectives and opinions from ours. Here are three reasons (and a few tools) that can help us to gain the full benefit of listening to someone who has different beliefs from ours.

Be curious about reasons: both your own and others

Our values represent what we believe is good and bad in the world. But it’s uncommon for people to ‘choose’ their values. Instead, we are far more likely to adopt the values that our parents have and the dominant values of the communities we grow up in.

Nevertheless, we hold our values near and dear to our hearts. They form the foundations of our lives and who we are as people. Someone who has different values from us can feel as though they are a world away from us. In reality, it’s likely they just had a different upbringing, with access to different information and abided by different norms.

One tool we can use for finding the reasons behind certain views is to think like a philosopher and ask “why.” The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates is well known for doing this, with what we now call the Socratic method. Essentially, every time a claim is made, we can ask “why” until we get to some root cause or foundational reason.

The Socratic method can be used to interrogate the reasons behind both our own beliefs and the beliefs of others. Another tool was developed by Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of Toyota, who would ask “why” five times in order to get to the root cause of a problem. The same can be done when trying to get to the root of someone else’s beliefs. Asking “why” of our own beliefs and those of people around us (and people who aren’t around us) is an important part of recognising the differences in our experiences, and ultimately helps to paint a clearer picture of how our values and beliefs develop.

Be open to a broader understanding of the world

There is no doubt that we live in an increasingly polarised and divided world. Thanks to the internet, diverse and extreme views can now be easily shared, amplifying voices around the world. Often times, this creates echo chambers that shield us (and can even villainise) dissenting voices.

On top of this, we are creatures of habit. Our social media algorithms show us things we like, we read the same news sources each morning, and we catch up with our friends, who likely have similar values to us. The ‘other perspective’ is often pushed outside of our world view and can feel distant. It’s hard to understand why someone could have such different beliefs to us.

When I took the time to listen with the intention of understanding, I found that I had significantly more impactful and meaningful conversations. Most of my (limited) knowledge of American politics and sociology comes from a classroom, so it’s theory-based knowledge rather than knowledge grounded in experience. It’s one thing to read statistics and understand a theory in a classroom; it’s an entirely different thing to hear a personal story.

Listening to my grandfather’s carer talk about her experiences added a level of humanity into what I had learnt in a lecture hall. As a result, I have more empathy and understanding for people who have different life stories, and therefore different perspectives from mine. Being empathetic doesn’t mean necessarily changing our views, but rather humanising and understanding the multiple ways people form their understanding of the world.

Knowing when not to listen

I don’t want to take away from how difficult it is to really listen to someone who has fundamentally different beliefs from us. It can be emotionally draining and it requires the right headspace. It can also be harmful for individuals of marginalised identities to listen to views that discriminate against them, and be told to give those views equal consideration to non-discriminatory views.

The Socratic method can also be useful for determining when not to listen. If a belief is founded on a discriminatory, hateful, or untrue statement, it can help to provide grounds for not listening to a person’s point of view. Philosophers sometimes think about this through the framework of intellectual virtues, or qualities in a person that promote the pursuit of truth and intellectual flourishing. These virtues (such as empathy, integrity, intellectual responsibility and love of truth) can help us to discern good from bad foundational reasons that we might find by asking why.

At the end of the day, if we’re in the right headspace and feeling ready to learn, it’s a worthwhile practice for us to learn to listen and understand the reasons why people hold different views. In turn, we can reflect on our own views, and increase our empathy for those with different world views.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: bell hooks

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Enough with the ancients: it's time to listen to young people

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Daniel Finlay Anna Goodman 6 JUL 2022

Nearly 20% of Australia’s population is between the ages of 10 and 24, yet their social and political voices are almost unheard. In our effort to amplify these voices, The Ethics Centre will be hosting a series of workshops where young people can help us better understand the challenges they face and the best ways for us to help. We’re listening.

You’re sitting at the dinner table at a big family gathering. Conversation starts to die down and suddenly your uncle says: “Have you seen that Greta girl on the news? I understand that climate change is a big deal, but the kids these days are so angry and loud. They’d get more done if they showed some respect.”

Many people under 25 have been in this position and had to make a choice about how to respond. This decision is often more difficult than it seems because there doesn’t seem to be a preferable option. Philosopher and feminist theorist Marilyn Frye gave a name to this kind of situation: a double-bind. In her essay Oppression, she defines the double-bind as a “situation in which options are reduced to a very few and all of them expose one to penalty, censure, or deprivation.”

Frye originally used the double-bind to talk about how women often found themselves in situations where they were going to be criticised equally for engaging with or ignoring gender stereotypes. The double-bind can be used to explain the difficult positions that anyone who experiences a negative stereotype finds themselves in and provides insight into why people with important perspectives often feel the need to censor themselves.

Let’s say we do choose to speak up. We can justify our anger. There are so many huge issues that impact the world – climate change, the pandemic, rampant inequality, and so on – and it feels like things are changing far too slowly.

Young people especially should be allowed to be angry, because this is the world we will inherit.

Unfortunately, it’s a common experience for younger generations to feel that their voices aren’t listened to or respected. Even though these reasons should more than justify the anger and frustration of young people, emotion can often (unjustly) obfuscate the reality of what we say.

So, let’s try the other way. We choose to not engage and instead let the comment slide. However, then we’re at risk of being seen as the “apathetic teen,” a narrative that has been perpetuated ad nauseam claiming that young people don’t really care about anything (which we know isn’t true).

Young people care about a lot, and have a lot to care about. Not only do they care, they act. A recent survey of 7,000 young people found that two-thirds of respondents seek out ways to get involved in issues they care about, and 64% believe that it is their personal responsibility to get involved in important issues. So, it’s not always easy to just let your uncle’s tone-policing go when you feel passionate about a topic, especially when staying silent can be as damaging as speaking up.

Here we see the double-bind in action: neither of the most obvious responses to the situation are favourable or even preferable. Because of a build-up of social and cultural assumptions and expectations, we’re often placed in a position where we seem to lose in some way no matter what we decide to do.

The Australian youth experience

Unfortunately, age discrimination towards young people doesn’t end at the dinner table. A 2022 survey conducted by Greens Senator Jordon Steele-John found that “overwhelmingly, young people are feeling ignored and overlooked”. Gen Z (people born between 1995 and 2010) are more likely to be viewed as “entitled, coddled, inexperienced and lazy,” which is having negative effects on young people’s confidence in the workplace. It doesn’t help that young people are hugely underrepresented in the Australian government and positions of power in the private sector.

Young people should not have to convince everyone that their voices are worth listening to. The combination of endless global issues and lack of representation in positions of power, which is compounded by a culture that doesn’t give appropriate weight to their contributions, creates a climate that leaves young people feeling frustrated and disempowered.

So, what can we do? As with most social issues, there isn’t one simple fix to the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of youth because it stems from a few different things that are ingrained in our society and culture. We can question our assumptions and those of others by recognising that “youth” as a social or cultural category isn’t really coherent anymore. There has been an enormous rise in the number of subcultures that are increasingly interconnected thanks to mass media and the internet, meaning that “young people” are more diverse than ever before.

Most importantly, we can bring young people together and into spaces where their voices will be heard by people who are in a position to make change.

As part of our mission to do just that, The Ethics Centre is developing a growing number of youth initiatives, like the Youth Advisory Council and the Young Writer’s Competition.

Through these initiatives, we are starting an ongoing conversation with young people about the areas in their lives and futures that they think ethics is needed the most.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships